‘Elemental’ VFX Supervisor Sanjay Bakshi Discusses The Combustible Elements Behind Pixar’s Oscar-Nominated Feature

Elemental, Pixar Animation Studios’ 27th feature, is currently nominated for multiple awards, including the best animated feature Oscar and six Visual Effects Society awards categories. This sweet-natured, romantic comedy has been a labor of love for director Peter Sohn, who took inspiration from his family’s immigrant experience.

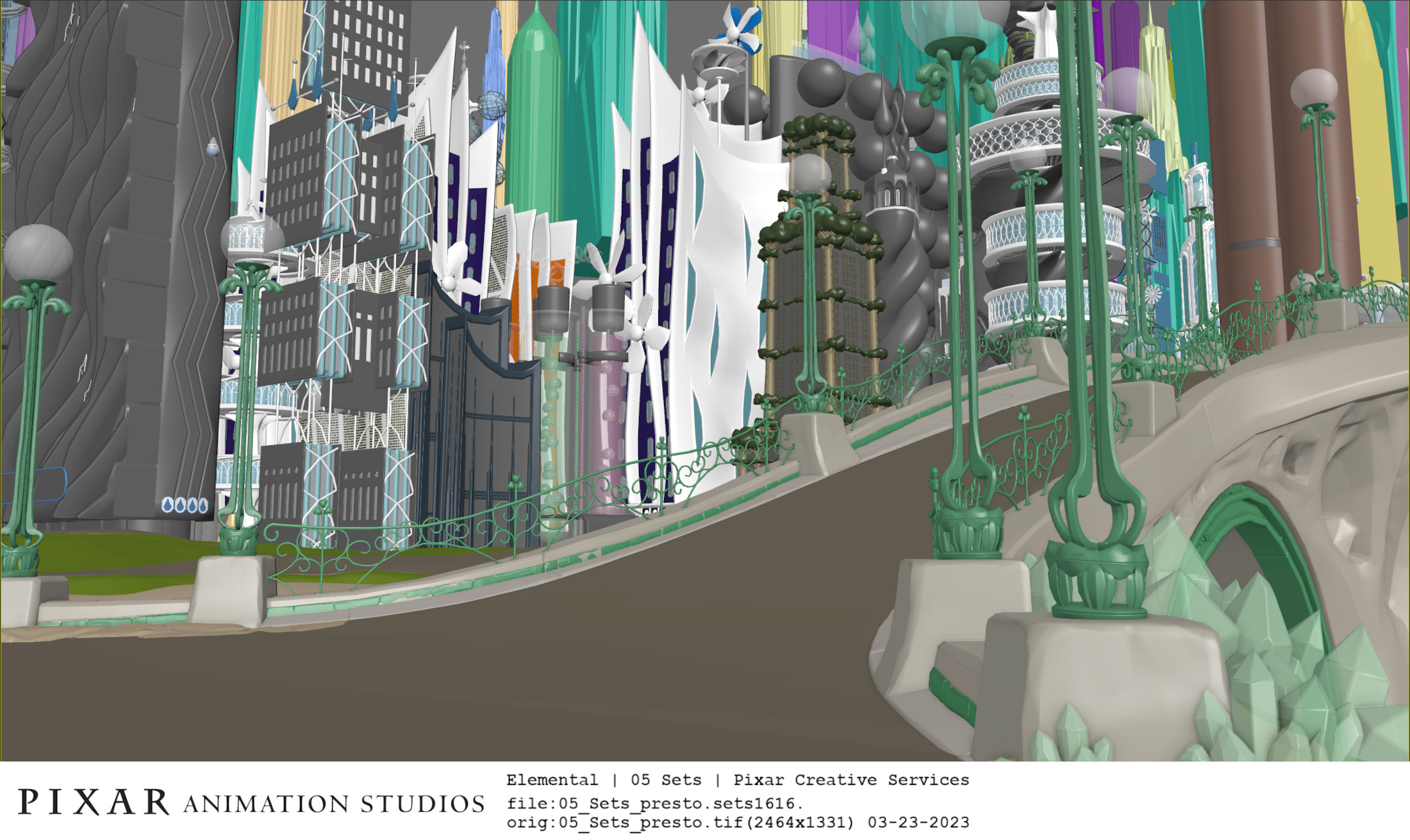

The result is a boisterous and luminously colorful rumination on compassion and the incompatibility of elements. Ember Lumen (voiced by Leah Lewis) plays a hot-headed Juliet as an anthropomorphic fire sprite who falls for her aqueous Romeo in gloopy water inspector Wade Ripple (Mamoudou Athie). And the star-crossed duo finds love in the segregated districts of Element City.

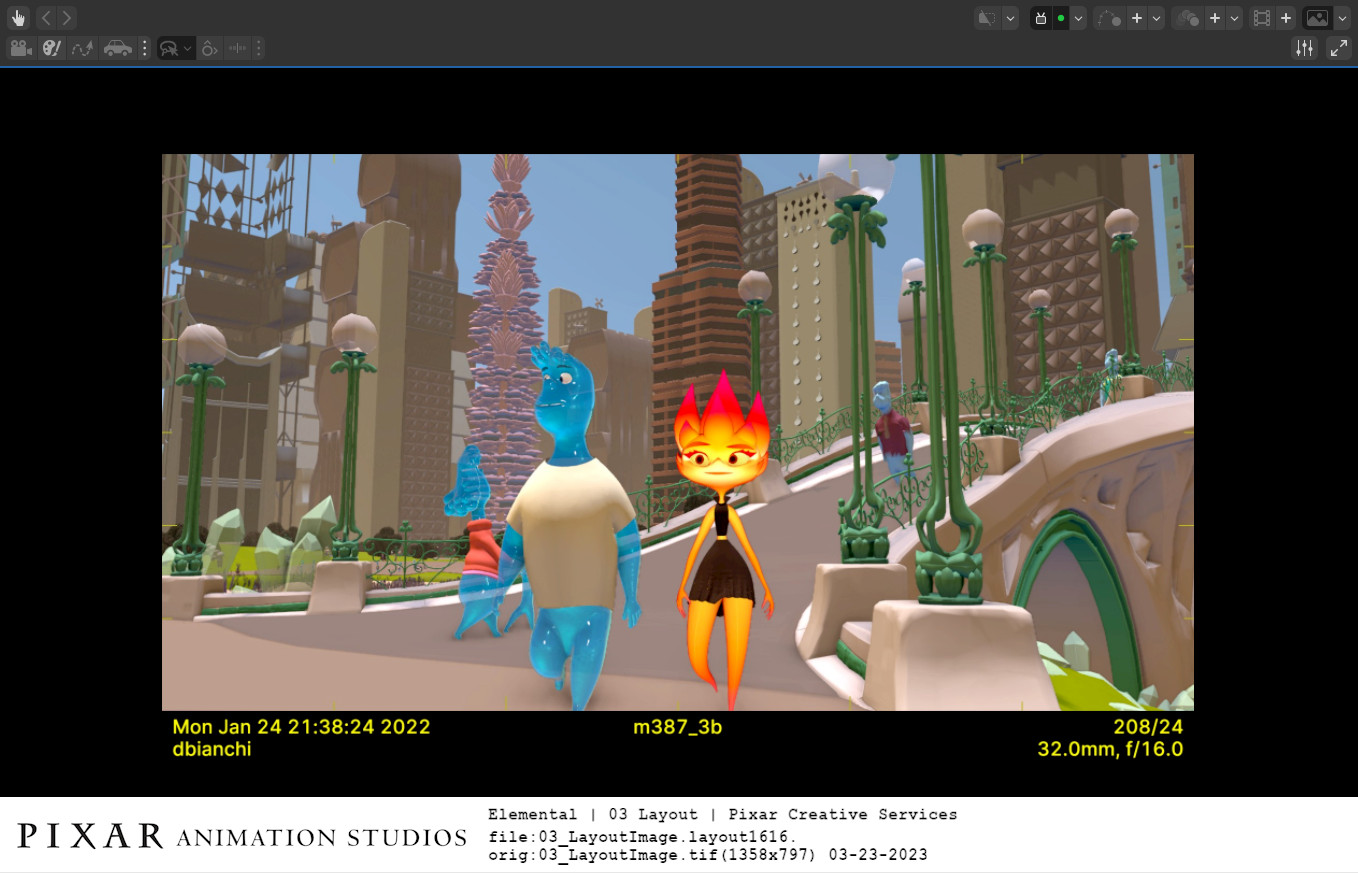

Elemental was in production at Pixar for seven years, three of which involved visual effects supervisor Sanjay Bakshi – former technical director on Finding Nemo, The Incredibles, and Cars. Among the tasks that Bakshi and his team faced while creating Elemental‘s ocean-front metropolis, a core challenge was to give animators capabilities to generate and perform characters made of fire and water – perhaps the most ephemeral of elements in the history of computer graphics. “We’ve been doing fire and water in computer graphics for a while, and it is still challenging,” Sanjay Bakshi admits. “To make characters that are expressive and people relate to was the trick. And that’s what drew me to the film.”

Bakshi first assembled a small team for rapid research and development on Ember. “We challenged ourselves to come up with an iteration of the character in four to five weeks,” says Bakshi. “We didn’t want to be too precious. We wanted to learn what we could as fast as possible. After that little sprint, we regrouped to review what we had learned, what wasn’t working, and what to try next.”

Ember tests continued for six months, followed by another year to dial in the character, heeding nature and animation references. “There were two ends of the spectrum,” notes Bakshi. “[In our research] we saw realistic, almost grotesque fire characters; and others, who were so simple. We wanted to be somewhere in the middle. The audience had to believe Ember was made of fire that could be extinguished. That was the premise of the film – if she touches Wade, it had to feel like there’s a possibility that she’d be extinguished. Then there was the other aspect of fire that is so interesting – and it’s why we stare at a campfire – it is constantly changing. Yet we didn’t want it to be distracting. It became a marriage of stylization and realism.”

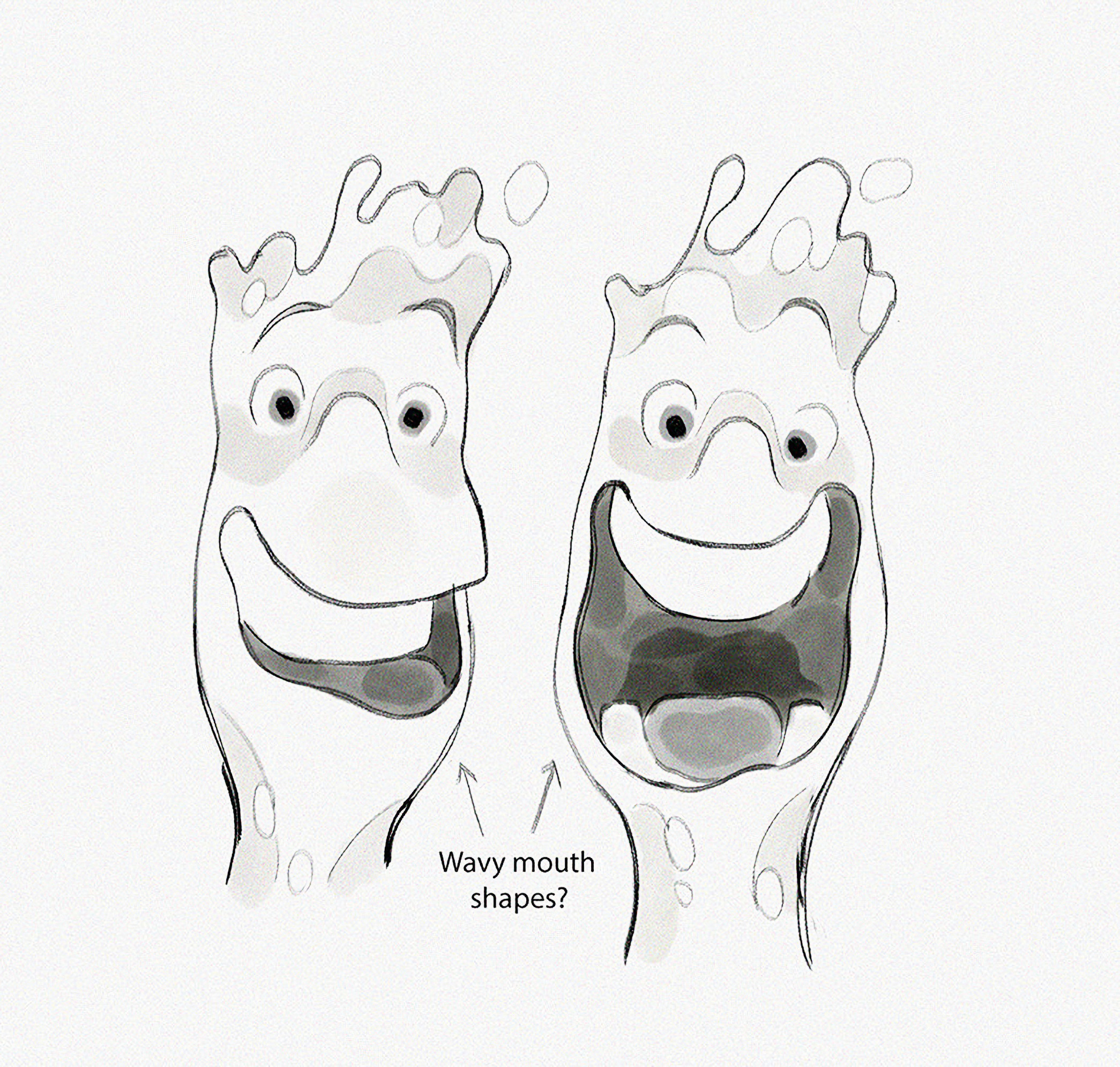

Stylization involved four styles of art-directed fire shapes contained in Ember’s fiery body. “We started with a fluid dynamics simulation and a pretty complicated rig that respected the form, a 3d model of Ember’s head. We constrained the simulation to that volume. But even then, the flames looked so realistic that we had to simplify the shapes. We used volumetric neural style transfer – an AI machine-learning technique that takes a picture that someone drew of what the flame should be and simplified flames to that.”

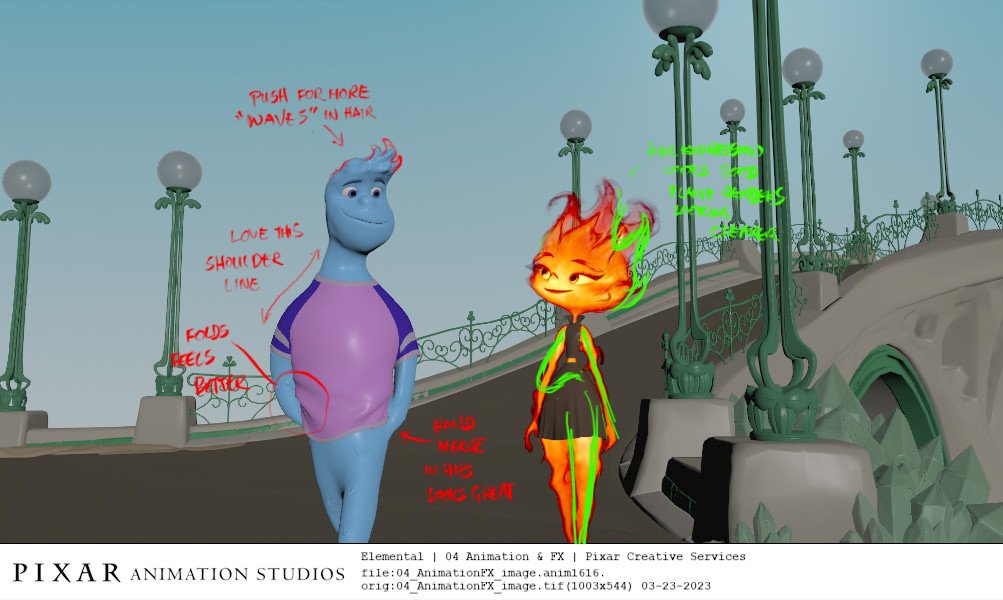

To help define character physiognomy, shading technical director Jonathan Hoffman built a volumetric shader to carve red outlines into Ember’s head. The lines took on the look of graphic brushstrokes, characterized in Pixar’s technical breakdown as ‘stylizing ribbons.’ The ribbons also served as line work for Wade’s translucent, watery features. “We used that to unify Ember and Wade design-wise,” Bakshi explains. “With Wade, we wanted to be realistic, similar to how a drop of water has a natural Fresnel [lens] effect on the edge of the silhouette. We amplified that on Wade to help him emote and push him from the background. For Ember, we used her silhouette edge, and we changed the color on it so that it was flowing and natural. Of course, fire doesn’t do that naturally, but it helped us ‘decorate’ the character, and it unified the design.”

Wade’s six-foot-something, sloshy, drippy nature also posed challenges in that, as well as his endearing malleable qualities, his translucent form behaved like a living lens. Pixar created water simulations using its powerful RIS (Rix Integration Subsystem) lighting model in Renderman and built internal shaders that allowed artists to fill Wade’s liquid volume with poetic flourishes.

“The first time we solved Wade’s face and filled it with water,” says Bakshi, “we quickly learned that was not going to work. We couldn’t read any of his facial expressions; it just looked like transparent water. We then played with what makes water ‘water’ without becoming lost in the logic. A vessel the size of Wade’s head filled with water might not have caustics or might not slosh around the way we wanted, but we added those effects so it felt like water. And that allowed us to concentrate on his acting.”

He continues, “We took liberties. We cheated Wade’s caustics, so they’re not exactly how light would play. There’s a subtle volumetric simulation to make him feel like he’s sloshing as he’s walking. We amplified Wade’s Fresnel effect, so there appeared to be a flowing simulation on top of his head. That made him feel alive and unified him with Ember – because she was always active. Drips come off him as he moves. We built in all sorts of effects, and then we hand-tuned him to the rig. That made him feel like water without getting caught up on the physics.”

Special moments in Ember and Wade’s relationship include an abstract Norman-Ferguson-like sequence that plunges into Ember’s eye to reveal her attempt to summon a tear for the first time in her pyrotechnic life. Peter Sohn conceived the scene to illustrate Ember’s growing empathy for Wade. “A lot of that was storyboarded and choreographed by a talented animator named Amanda Wagner,” notes Bakshi. “We then gave those boards to very talented artists who come up with ways of making it feel abstract, and we let them play for several months. We didn’t constrain them to any tool or pipeline as they worked with Pete.”

When Wade and Ember summon the courage to kiss, sheltering under a canal bridge, Pixar artists brainstormed a suitably impactful treatment. “That was almost an effects dance,” says Bakshi. “Their first touch, the amount of steam that comes off, the way the water and the fire reacts, that was all drawn out on paper. We talked through how they react and it builds, and then let the effects artists match the intent. It was a one-off, so we didn’t need to build a rig. We brute-forced those shots and took the time to make it right.” Principal lighting artist José Luis Ramos, Pixar director of photography Jean-Claude Kalache, and Pixar Lightspeed artist Jeremy Heintz generated transcendental lighting effects. “We wanted it to be magical, like a heightened realism, grounded but also so romantic. There are twinkling lights, reflections in the water, stylized bokeh, and lens effects. We threw everything at it to get it to be as beautiful as we could.”

The synergy between visual effects and emotional storytelling required a unique approach to effects artists’ and animators’ roles. “They had to work together in a way that hasn’t happened before,” Bakshi concludes. “When Ember gets angry, for instance, that had to be choreographed by the delicate touch of an animator. We built controls so the animator could not just change Ember’s facial expression and body language; they also controlled the roiling nature of her fire. They could make the flames intensify and become more jagged, go from red to purple, and make her as bright as she can be. And those parameters controlled aspects of the fluid simulation. We invested a lot of time in building those controls so that the animator could create that performance. That was the dance that we had to do.”

Pictured at top: Elemental concept art. Artist: Lauren Kawahara

Photo captions provided by Pixar.