Editor Janus Billeskov Jansen Explains His Role In Constructing The Narrative Of ‘Flee’

Flee, an animated feature film by Jonas Poher Rasmussen, is about a man (Amir) recounting his experience being forced to flee Afghanistan while also struggling with his sexuality. The film is a fascinating and poignant work that fuses documentary, animation, and archival footage over very distinct segments that shift between Amir’s present as he recounts his story to a friend and the recreation of Amir’s past experiences.

The fact that Flee is nominated for best documentary feature, animation feature, and international film speaks volumes about the creators’ success in blending different visual styles, tones, and paces.

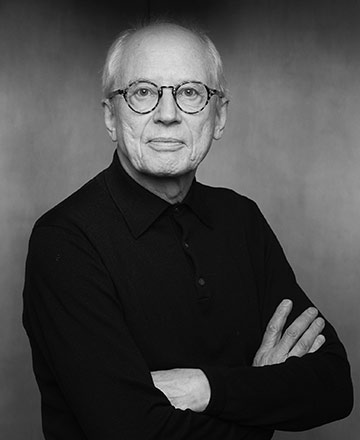

To glean insight into the challenges of working with documentary and animation elements, Cartoon Brew spoke with Flee’s award-winning editor, Janus Billeskov Jansen (Another Round, Pusher II, The Hunt, The Best Intentions) via Zoom. Jansen, who has been Denmark’s go-to film editor for decades, discussed how he collaborated with the director to construct the narrative, the film’s impactful ending shot, and the hard work of integrating archival footage, audio recording, and animation into a fully-realized whole.

Cartoon Brew: You have decades of editing experience working on documentaries and live action films, so how did Flee end up in your lap?

Janus Billeskov Jansen: I knew Jonas [Poher Rasmussen] from his time at film school. He was at a different kind of film school in Denmark called Super 16. It was created 20 years ago or so by a group of young people who had been refused by the Danish Film School. So they created their own school, and it has actually grown into a very interesting and successful alternative film school in Denmark. So I knew Jonas from there because I would sometimes teach there. I was also involved in his last project at the school. Later, he continued working on documentaries, and I would occasionally help supervise the editing process of his work and give him my reactions.

Flee ended up at Final Cut For Real, a production company I am a part owner of with Signe Byrge Sørensen. So it was very natural that we started to work together. He came to us with these ideas about seven years ago. It started out as an ordinary documentary. Later, it turned into an animation. And it was very interesting, because it would have been very difficult to do a regular documentary. Not just because Amin wanted to be anonymous, but because it would have been very complicated to film and to get footage from different periods of time.

Can you talk about your role as editor of Flee? In cg animation, for example, the editor is involved in planning, whereas in a more traditional film, the editor generally does a lot of the work after the footage is done.

Jansen: Yes, I was there from the beginning. When they first started talking about it as an animation, they laid out the characters. We were doing a lot of editing for a film that has not yet been shot. We had all these dialogues between Jonas and Amin that we put together in lines of voices and then animated on top of those a little later. We went back and forth a lot. We changed the rhythm of the story, the order of the scenes, and we also condensed it more. This was important for production because the film animatic we delivered had to be the exact length. For me, it was really to use all my skills from 50 years of editing and to say, “How long are we going to be on this shot?,” “Should it be a wide shot?,” “Should it be closer?”

When they started talking about it being an animated film, they laid out the individual characters, just to show what they could look like at different ages. We had some of the layout of some of the re-enactment parts, and we had a huge amount of archived material from different places. Jonas had already gone out and done a lot of research. And he went out to find the original buildings to see if there was any archival material around. But that developed during the editing. We had started editing the scene where the two sisters go with human traffickers and end up in Stockholm on this ship.

What we didn’t have was the part where the man was on the sinking ship before being taken into custody and placed in this terrible prison. It was during the editing that we found the actual footage. Amin remembered seeing a television crew there and thought they might have come from Finland. So we actually found the original footage and Amin recognized all the different people. So that particular scene grew and became a bigger story. Jonas had to go back and interview Amin to focus on more details from that particular moment.

The whole setup of Amin lying on the couch there with the camera, where you see the camera and you have this top camera on his face, that is one to one. It was something that you could actually animate on top of. What we do with this kind of dialogue is to shorten it, compress it, and make it more clear for the actual story. Which we normally do for every kind of documentary. There’s nothing strange about that. But when we animated, we could do it as one scene without any cuts in it. Although throughout the film, we have these out of continuity cuts where it’s jumping in the animation. We didn’t necessarily have to do that; we could have smoothened it all out, but we wanted to keep the audience aware that this is actually a documentary film, a true story.

So, Amin must have been heavily involved in the re-enactment parts, since it’s his memories being reenacted and animated.

Jansen: It’s something that went back and forth between Amin and Jonas as the director. I decided that I would not really meet Amin. I wanted to be in the same position as the audience. But throughout the editing, we realized that we had a lot of different pieces that we needed to explore more. Things like the inner life of the boy. So then Jonas would go back and forth with the particular purpose of digging more into that part of Amin’s past. Those were not filled with cameras, but it was a similar setup. Amin was lying down, with two microphones set up. The way that you talk is different when standing, sitting, or lying down.

There was also the issue of getting into Amin’s memory. He didn’t necessarily know what Jonas wanted. The important thing in this storytelling is that you want to have that feeling in his voice that he is digging into his memory. And the way the voice floats there is an important part of what this film is about. This is Amin’s real voice, and on top of that is animation. So it’s like these two elements are talking together, and out of that comes something completely new. And that’s very interesting. When we deal with his conversation with Jonas or his voice-over in explaining some of the different animated scenes, the tone is so important. And this was something Jonas and I carefully orchestrated throughout the editing.

How much live action footage did you have? What kinds of discussions were there about balancing the live action with the animation?

Jansen: All of the backstory, the childhood, was all totally animated. There’s no original footage for that. In the conversation on the couch, there was a lot of footage, but there was also a lot of recorded talk that wasn’t filmed. In the interaction between Amin and his boyfriend, a lot of it was filmed. That kind of dialogue was actually happening for real, and then they animated on top of that. But we also had to get deeper into the emotional situation at times and had to add new lines there.

What I’ve always said about documentaries is that we use 90% of the editing time to figure out what the exact ending of the film is. So many times, the beginning and end of the film are the most complicated things. With Flee, this wasn’t a problem. Jonas had sorted it out from the very beginning.

Let’s talk about the ending. The final shot is quite powerful, but it could have potentially come across as a bit sentimental or forced. Instead, it’s like a bridge between animation and reality. It’s really, again, reminding the audience that this isn’t some fictional cartoon, this is a true story about a real person.

Jansen: We discussed the last shot a couple of times. A couple of minutes before that, they had decided to move in together. Moving into a house is taking responsibility for each other. That’s the implication of it. So we had that scene and that was actually shot so that the dialogue there was really happening in that emotional situation. But the interesting thing there is that the film is operating on two levels: He is the grown-up lying on the couch talking about his childhood and family story and struggling with these secrets he’s been keeping about his homosexuality. That’s one thing.

But it’s also a story about a grown up man lying on a couch telling his childhood story, and by doing that, it’s doing something to him in the present. What kind of knowledge and reflection does it give him for his life going forward? And that was something we needed to go further into throughout the editing of the film. So that really suddenly expanded and it was very interesting to work with that part of it. Secrets aside, you also have this burden that’s been placed on Amin’s shoulder. He was the one who got opportunities, and he felt pressured to succeed for his family.

Well, that final shot nicely reflects that, because you get this subtle transition from animation to live action. It’s almost like it’s time for Amin to let go and start living his own life.

Jansen: There’s a parallel to the earlier scene where they are looking for a house, but Amin clearly doesn’t want any part of it. So the last scene mirrors that one because now they’re connected finally. We almost cut that earlier scene. We thought it might be a little boring, but at an early screening, people reacted very strongly and really understood it. Also, for the final shot, we did have live footage before. Yes, it was archival footage that was squared in on the canvas with some historical distance, but I think it prepared the audience for the final shot.

What did you come away with after working with animation? Was there something that may have surprised or challenged you?

Jansen: For me, in feature films, we normally start editing throughout the shooting. So you can go back and ask for additional shots or things like that. They are in a hurry and it costs money, so when you ask for something, you really have to think carefully and not ask too much. But with Flee, it’s just saying, “Oh, shouldn’t we have a wide shot of Kabul before we actually get into the scene with the mother and sisters around the table there?” Then they just say, “Okay.” If that was a live shot, it would be complicated and expensive, but here they can just draw it.

What I think was a tough thing was to be sure that the length of the shots in this very rough first animation was what they should be in the final film. That was a unique experience.

And then another thing that was interesting was that it was close to the end of the editing. We had a couple of screenings with these rough black and white images on the screen. What was fantastic was that it still moved the audience, some to tears. At first, I got a little scared because I thought, if these black and white, very poorly animated pieces can take the audience by the heart, will the fully animated version still have the same effect? Can it live up to the audience’s imagination? But it turned out to be very good. The animation really gave Amin a fantastic character.