Behind-The-Scenes: Tricks And Techniques That ILM Used To Transform Characters In ‘Bumblebee’

When Industrial Light & Magic worked on the first live-action Transformers film, released in 2007, the vfx studio pretty much had to invent a way to make the giant robots transform from vehicles to humanoid bots, and vice versa.

Over a number of sequels, and now with the franchise’s reboot, Bumblebee, ILM has mastered the technical animation art of the transformation. For audiences, watching them take place on the screen, with many pieces of metal seemingly folding away into pre-determined locations, never looks simple.

Cartoon Brew asked ILM visual effects supervisor Jason Smith and co-animation supervisor Rick O’Connor to break down how the transformation effects have evolved, from Michael Bay’s first blockbuster Transformers to Travis Knight’s newest incarnation with Bumblebee.

Giving animators more control of rigging

“On the first film [in 2007], we had zero idea how we were going to accomplish the transformations,” said Smith, who has now worked on four of the Transformers films. “I remember we even did a test early on where we were really trying to rig pieces of the truck to become pieces of Optimus Prime, one-to-one, without cheating. We were almost like toy designers saying, ‘Okay, how is he going to transform?’”

What ILM’s artists soon realized, however, was that they could cheat the transformations (i.e. not every panel from a vehicle had to match a panel on the humanoid robot), and that every transformation would actually be different depending on the action at the time and the camera angle.

Smith’s role on that first film was creature supervisor, which meant he was in charge of rigging and providing the animators with the tools they needed to accomplish the transformations. He wrote some ‘dynamic rigging’ tools called the ‘TFM’ tools.

Explains Smith: “What those tools allow the animators to do was, on the fly, let them grab some pieces, regardless of how they’re rigged, and say, ‘I want to move these as a unit.’ And, they were given a few hinges that they can place, where they say, ‘I know I’m going to want it to fold back that way, so I’ll put it in here. I know it’s going to spin while it does that, so I’ll put a hinge right in the middle that can spin.’ And, once they’ve placed those hinges, they can push a button and that becomes a live rig that they can now animate as pieces along those hinges.”

Smith says giving the animators controls that were normally the domain of the riggers was the main benefit of the TFM tools. “The alternative would’ve been a nightmare. It would’ve been, ‘Okay, let me get on the phone with the creature TD [technical director], and that creature TD’s very busy moving robots and now I’m asking for a brand new rig that’s got to be a specific thing.’ And, ‘Oh, that’s almost right, but it needs to get sent back.’”

The TFM tools proved incredibly successful, and were further utilized on other films that had creatures or characters with hard surface animation, such as Iron Man for the lead’s weapons, and of course subsequent Transformers films (Smith has had a major hand in how the vfx studio has approached rigging; along with other colleagues at ILM, he was recognized with a Technical Achievement Award by the Academy in relation to ILM’s BlockParty procedural rigging system).

How a transformation animation happens

On Bumblebee, animators at ILM benefited not only from improvements in the rigging system, but also tools that enabled them to place a rudimentary transformation into an animation scene. Previously, the robot would simply turn off and a car would turn on to indicate roughly when the transformation would be while the animator was working on a scene.

“This new approach helped immensely because the animators could dictate how long a transformation needed to be within the given guidelines of the performance,” said O’Connor, also a veteran of several Transformers outings. “Travis [Knight] was so precise with his storytelling and how long things would take, and with the rhythm of the narrative, that it was just so beneficial to give the animators something they could actually ‘plop’ into their scene, as opposed to having to wait.”

For example, the animators might have a cg Bumblebee in car form in the scene that needed to transform to robot form. The car would be imported (into Maya) with a set of internal controllers. The transformation seen by animators would, at first, be a ‘pre-baked’ version of the transformation. “Then,” described O’Connor, “if you needed Bumblebee running around with the pieces of the transforming car on him, he could have all this extra garbage hanging off of him. So we’d dictate the transformation with this slider set that would be imported into Maya, and when you needed to, you just turn it off, so that we wouldn’t see it any more.”

“Here,” added O’Connor, “the animators could say, ‘The transformation needs to be 25 frames long, or it needs to be 40 frames long,’ based on the rudimentary out-of-the-box transformation. And then once Travis bought off on that, we’d give it back to our transformation experts, who would then take the painstakingly long time to do the really cool work.”

The Transformers legacy

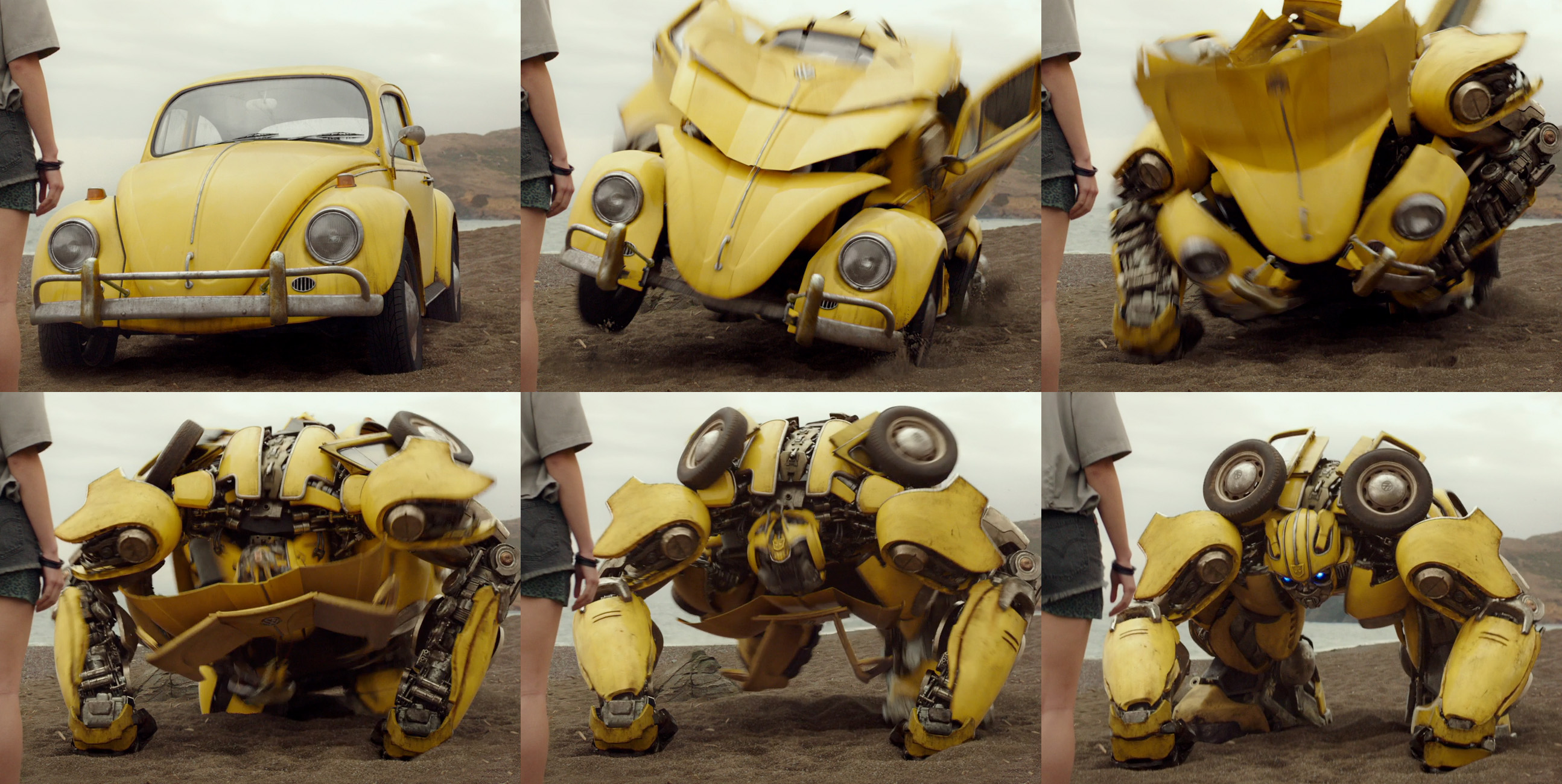

Bumblebee’s distinction from the former Transformers films is that it more closely resembles the robots and vehicles from the original 1980s cartoon series. That translated into the approach to the transformations themselves, as O’Connor observes.

“Luckily Bumblebee works in such a way that all the pieces on his body actually are designed based on what the car is. It’s not like the past movies where Optimus Prime looked like a knight in part four and five, where the car pieces had to hide underneath his body. This Bumblebee design was just perfect for the old school transformations, where you can actually see where the pieces go. It just made sense that his chest is the front of the car, and pieces of his back and feet are the back of the car. It worked so well in how he unfolded into the nice organic change, that it just lent itself perfectly from car to robot.”