Animation is the Ultimate Expression of Hope: An Interview with ‘The Breadwinner’’s Nora Twomey and Saara Chaudry

High above Hollywood, a capital of escapism, director Nora Twomey is talking about the need for empathy, in a war-torn world on the brink of global catastrophe.

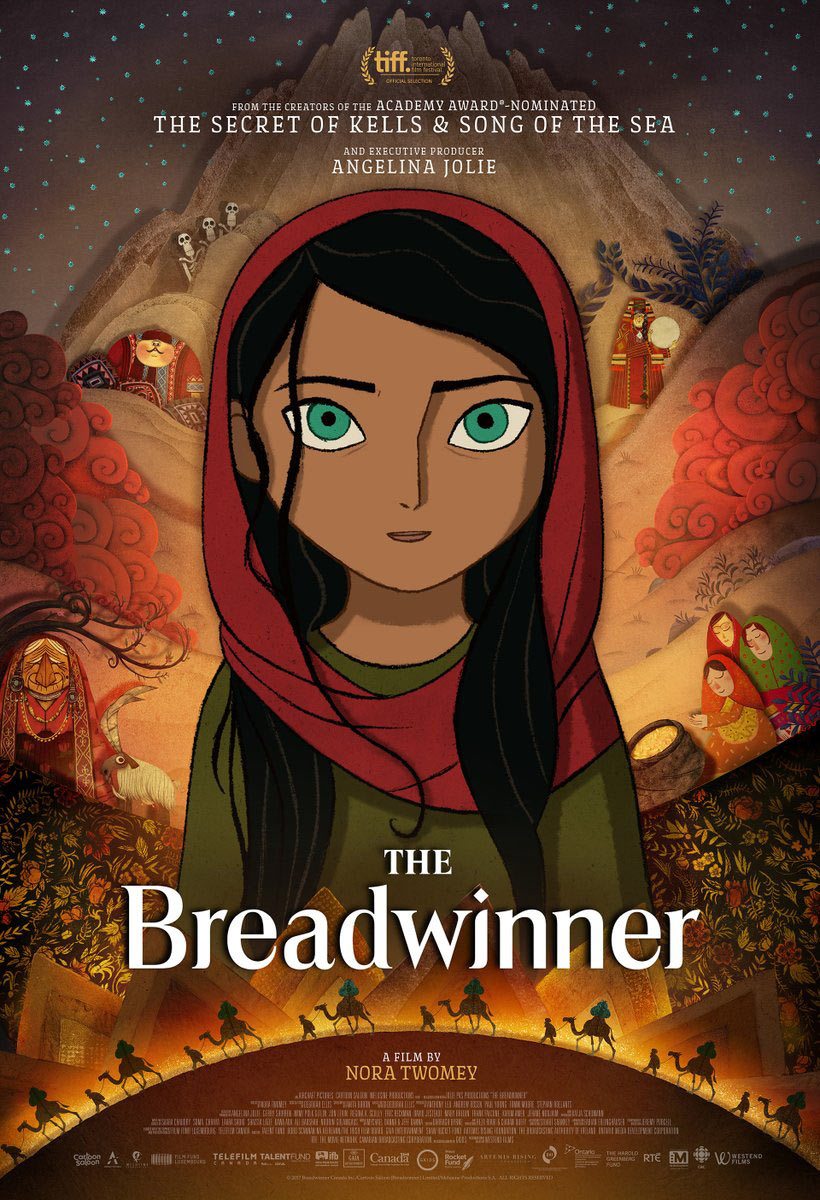

Two nights before, executive producer Angelina Jolie premiered their animated wonder, The Breadwinner — an adaptation of Deborah Ellis’ novel about an Afghan girl who pretends to be a boy to survive the Taliban on the eve of the longest war in American history — to a festival audience demanding respect for animation as cinema.

Now speaking softly but earnestly about animation’s universal language, Twomey, who co-founded the impressive Irish studio Cartoon Saloon with Paul Young (executive producer of The Breadwinner) and Tomm Moore (director of Song of the Sea), is sounding like another leader we need in the charge toward a more productive, relevant art form.

“We’re in a time when we are looking to pull cultures apart, and tell them they don’t have the right to tell their stories, which is the opposite of what we should be doing,” Twomey told me in a Hollywood hotel suite adjacent to the Animation Is Film festival, shared with Saara Chaudry, the voice of The Breadwinner’s persevering protagonist, Parvana. “We should all be trying to tell each other’s stories, to understand and participate in each other’s stories, so that we can learn about each other and have some of hope for the future.”

Opening today in L.A. (Nuart Theatre) and N.Y.C. (IFC Center, The Landmark at 57 West), The Breadwinner, being a story about storytelling, finds metafictional hope where it can. From the stories of Parvana’s disabled, quickly imprisoned father to cinematic expressions of Afghan folklore and legend, from letters of tragedy Parvana reads to an ally on the streets to sudden interrogations in the market that can lead to sudden death, The Breadwinner artfully, painfully communicates humanity’s powers to communicate both hope and harm in equal measure.

As such, it stands out among other more mainstream awards season candidates like a must-read message from turbulent planet. I spoke with Twomey and Chaudry about animation using its singular power of expression to make the world a better place, before it is too late.

Cartoon Brew: The Breadwinner is the only awards season animated film I know of that currently has its own study guide…

Nora Twomey: I suppose that I would never come at a film with an agenda, in terms of message. I think if I tried to do that, I would probably fail miserably. All I can do, as a filmmaker as well as a mother, is to try and make films that have resonance with me. At the end of the day, I make stories for myself, first and foremost. And I feel that if I make a film that expresses a story from — but also to — me, then I have succeeded in some way, especially if I can gather people around me who also have stories to tell.

The Breadwinner is Deborah Ellis’ book, but it’s also the testimony of all of the women she spoke to in refugee camps in Pakistan, as well as the Afghan caste members who told their stories to inform me and the rest of our cast and crew about the complexity of the story we were trying to tell. And it’s also other people’s stories: We had a young Iraqi woman working who joined the project as a filmmaker and very much invested herself in this film. It’s people from different cultures; it’s more than the sum of its parts, and way more than I could ever have made as a solo project.

The Breadwinner powerfully, and persuasively, balances its myriad sociopolitical, stylistic, and historical components…

Nora Twomey: If anything, The Breadwinner is a massive collaboration between over 300 people, all honestly giving more than they usually would on a film, for their own reasons. And you’re talking about people with different political perspectives as well – on the world, on human rights, women’s rights, and the rest of it. But they are all filtering into the one story.

As a director, you just try to tell the best story that you can, to try and make characters that are as true as they can be, that there is a rawness in there, that there is truth and vulnerability. To be able to get that from your animation performances, to be able to get that from the rendering of the backgrounds, to be able to get that from your voice cast, is always something that you’re chasing after. I mean, I don’t mind making flawed films. If you can make a film that has flaws and cracks in it, that is at least searching for the truth, as opposed to making something that is by-the-book or very polished. For me, that is the joy of filmmaking.

I’ll say that Cartoon Saloon hasn’t made a flawed film yet, which may be another way of saying that the pressure is on. But from The Secret of Kells and Song of the Sea to The Breadwinner, Cartoon Saloon makes films that aren’t, for lack of a better term, disposable.

Nora Twomey: I think we at Cartoon Saloon are in a very privileged position. Number one, we are a company created by a group of friends, in order to do the things that we love. And we love telling stories and we love drawing pictures. [laughs] So, that’s where we start from.

And then we live in a country with a film board that supports independent film, and the type of stories we want to tell. That’s a massive boost. We have a tax break in Ireland, and we have co-production partners in different parts of the world. The Breadwinner was made with Canada’s Aircraft Pictures and Melusine in Luxembourg. So it gives us freedom when we can find like-minded studios around the world with people who share our sensibilities and want to create the kind of stories that we want to create. And it’s a freedom to make mistakes; we don’t have a huge financial pressure breathing down on us.

Your social media feeds keep telling me you’re hiring.

Nora Twomey: Yeah, things certainly are great in Ireland’s animation industry at the moment. But all of these things ebb and flow, you know? As successful as things are now, who’s to tell what’s going to happen in the future? When you have this kind of support, films like The Breadwinner become an awful lot more easy to make. It certainly made it a much easier experience for me, as a director, to make a film in that environment.

That sounds like an excellent argument for national funding for cinema…

Nora Twomey: Absolutely, yeah. It asks us: “What do we want to do as a global society? What kinds of stories do we want to tell our kids? Are we pushing the toy everyone wants for Christmas, or are we trying to give our children tools to deal with the world?”

For me, it’s the latter. I mean, I made a choice in my twenties as to what I was going to do. Was I was going to work in a big studio, or was I was going to try and give myself that feeling where it’s six o’clock in the evening and I want to continue working? I wanted to have that exuberance about what I do.

Nora, you’ve said regarding The Breadwinner that animation can help equip our children to deal with the world they’ve inherited. How old do you and Saara think children should be to see it?

Saara Chaudry: The poster says PG-13, but I read this book when I was nine years old, and it did not scare me, and it did not make me feel uncomfortable. Being an absolutely lucky child from Canada, all it did was make me ask questions. After I read the book, I asked my mom a question each day, sometimes 20, because it was all I could think of. If I could handle that at nine, I think as long as children understand what they are about to watch, and as long as they’re prepared to later understand the different concepts and themes of the film, then go ahead and watch.

Nora and I always talk about this: Parents and adults will come out of the theater with tears in their eyes, sometimes worried about their children. Should they have watched it? Should they have been kept at home? But the children come out and they’re laughing about Parvana’s argument with her sister. They find relatable things like that. A girl about seven watched a screening and came up to me after and said, “I want to be just like that girl.” And it just warmed my heart. She kept asking me questions about the movie and the book, which she was also reading. But I found the fact that she wasn’t scared, but wanted to learn more and be like Parvana, to be so special. As long as children are ready to ask questions and learn more about their world, they should watch The Breadwinner.

Nora Twomey: Our job as adults is not to protect children from things that might scare them. Our job is to help children deal with things that will scare them, to deal with their own fears. Because if they grow up not knowing about any of these things, all they are going to do is ignore them, or oversimplify them, or listen to soundbites and not be able to deal with them. If children are exposed to issues explored in The Breadwinner with their families in a supportive way, they will grow up to be stronger adults with the capacity to actually make changes in the world, which to me is the ultimate expression of hope.

How do you think The Breadwinner can equip children to deal with the overheating, war-torn planet world we’ve so tragically created for them?

Nora Twomey: For me, it’s all about empathy. Roger Ebert once said that films at their best are giant empathy machines. For us, a character like Parvana, through all her strength and vulnerability, is still just one human life on this planet, and that can be taken away at any moment. Yet she has inherited all of this history from her ancestors, and she has the capacity to transform her future. She is a character with flaws, which I love. She has a difficult relationship with her sister; she regrets something she did that she felt made her dad think a little less of her. These are all things that are very human, and have happened to me in some shape or form throughout my life, and yet they are still quite universal.

So how does The Breadwinner equip young people? I think the film nods to the complexity of all of the underlying issues that create environments where someone like Parvana would have grown up. I don’t have all the answers to what’s going to happen, or what should happen in conflict areas around the world. I grew up in the ’70s and ’80s in Ireland — where we had our own troubles, and our own political situation that took decades to arrive at a level of stability — so I have no blinkers on my eyes, in terms of understanding the vulnerability of peace, or the preciousness of hope and human life. For me, The Breadwinner is a celebration of all of those things.

Escape, not empathy, seems the goal of much of American culture these days. Do you think animation should be seeking less ways to escape the world?

Nora Twomey: I think all storytelling endeavors are one human being reaching out to another. To say that, for this journey at least, you are not alone, and I understand what you are going through. For me, all storytelling is about that. It’s about that moment where you are trying to understand what your life is all about. And you may never know! [laughs] But you will know that someone else is also experiencing it. For me, that’s what it’s about.

Animation — particularly this kind of co-production, with over 300 people from different countries and cultures bringing all of their skills together to make one film and tell one story with one central performance — is, for me, the ultimate expression of hope. We can use different cultures to tell a universal story. In The Breadwinner, Parvana wears the crown of a 2,000-year-old nomadic princess, which is based on an artifact dug up in the ’50s in an area of Afghanistan called the Hill of Gold. To me, the crown represents the Silk Road, the mix of cultures that ran through Afghanistan, and the idea of mixing cultures to tell stories, which is very potent.

Because we’re in a time when we are looking to pull cultures apart, and tell them they don’t have the right to tell their stories, which is the opposite of what we should be doing. We should all be trying to tell each other’s stories, to understand and participate in each other’s stories, so that we can learn about each other and have some of hope for the future.

Cartoon Saloon’s work embodies that philosophy: The Secret of Kells and Song of the Sea explore Irish folklore and myth; The Breadwinner is anchored in Afghan culture; and your amazing first film, From Darkness, is based on an Inuit legend. Yet they all teach that storytelling, no matter its geographic origin, is a universal mechanism for unity.

Nora Twomey: Yeah, absolutely. As parents, I think our first urge is to tell our children a story. It is often the first thing they hear from us, which is utterly universal. Certainly, when The Breadwinner’s screenwriter, Anita Doron, looked at what kind of story we could tell for Parvana, it was a universal one, not specifically an Afghan one. It is that story of a hero with three tasks, which is told across different cultures. We very specifically tied it to her own family’s mourning, something that was impossible to express on a day-to-day basis, for fear of losing what sanity their family had.

At our cast and crew screening in Toronto, a cast member brought her dad, who had come to Canada from Afghanistan during the communist era, I think. I could see them holding hands all through the film, and afterward he talked to her in Dari, which is their language, about things that had happened to him and things that he had seen that he hadn’t expressed before. Because you can imagine, you can’t dwell on things when you need to raise a family in Afghanistan; you can’t express yourself if you want to hang on to your sanity.

Stories like The Breadwinner are a means by which we can open a little door to some of these areas in people’s hearts where they keep all of this stuff. Whether it be on that level, or whether it be on the level of a Western family with their own issues to deal with, including lack of families, there are hearts we can explore with films like The Breadwinner in a way that will start conversations.

How do you feel The Breadwinner, which opened the inaugural Animation is Film festival, exemplified the event’s aspirations for animation to be taken more seriously as a cinematic art form?

Nora Twomey: Seeing animation being encouraged like this is incredible. Standing in the theater and watching people walk into the different screenings is such a boost. There is a market for this; people are hungry for films that tell different stories. In terms of animation being film, I’ve probably gone through my whole life trying to fight against animation as genre. [laughs] And I’ve had people tell me that they forget that The Breadwinner is animation, as though it’s an insult to call it animation. I remember being in the back of a taxicab telling the driver about The Breadwinner and he said, “Why don’t you make it a real film?”

Saara Chaudry: There is an assumption that it’s supposed to be a live-action film, which is what I am often asked when I tell people what The Breadwinner is about. But animation isn’t supposed to be anything; you can take it in whatever direction you want. When people finally watch The Breadwinner, then they often understand why it is an animated film. It’s fantastic that we have such an incredible movie, based on an incredible book, in a festival that celebrates the choice to use animation.

The Breadwinners opens today in Los Angeles and New York City, and will continue to expand nationwide and globally throughout the winter. For a list of screening dates and cities, visit the film’s website.