Animation Plays An Important Role In The New Indie Drama ‘We the Animals’

Earlier this year, Cartoon Brew reported from the Sundance Film Festival on several new live-action features that effectively employed animation as an enriching narrative device.

Among those mixed media works, the unforgettable standout came in the form of Jeremiah Zagar’s We the Animals, the film adaptation of Justin Torres’ novel of the same name, where artist Mark Samsonovich was tasked with translating the protagonist’s innermost feelings and chaotic thoughts into hand-drawn animated sequences.

Introspective and artistically inclined, 9-year-old Jonah (Evan Rosado) is the youngest of three brothers growing up in a dysfunctional household with their white mother and Puerto Rican father. To withstand their turbulent circumstances, Jonah and his siblings depend on their unspoken and seemingly unbreakable bond. However, as he becomes conscious of his sexual orientation, there is a schism between them. In the absence of an outlet to communicate his frustration or a sound adult to soothe his doubts, the kid draws vivid accounts from his uneasy imagination into his journal.

Those sketches come to life on screen thanks to Samsonovich, who personally rendered more than 6,000 drawings and subsequently animated them. We the Animals provided Samsonovich an immersive encounter with the painstaking artform of animation – one he hadn’t previously tried his hand at. Intrigued by this powerful usage of animation, Cartoon Brew spoke with Samsonovich about the significance of his laborious efforts in the final product and the road to getting his first professional credit as an animator in one of the most original American independent films of the year.

Cartoon Brew: Your work on We The Animals adds indelible depth and visual complexity to a movie that’s already beautifully elaborate. Did you join the project specifically to work on the animation or what was the onset of your involvement?

Mark Samsonovich: My cousin Diana Eliazov, who is a cinematographer, is friends with the director Jeremiah Zagar and Jeremy Yaches, one of the producers of the film. She saw that they were looking for an illustrator to come and design the prop of the journal that Jonah, the main character, has in the film. So originally, I got brought in to design the journal. I sat down with Jeremiah in a cafe and he showed me a clip from the movie, the scene when they’re in the kitchen and Pops is teaching them how to dance. He tells the kid, “Dance like you’re rich, dance like you’re poor, now dance like you’re Puerto Rican.” I saw that scene on mute actually, there was no sound to it, and I was so moved by it that I decided to take on the project.

I showed Jeremiah the initial drawings that I thought could work for Jonah’s drawings, for his journal, and he liked them right away. He told me that he was having trouble finding an illustrator, and it seems like it worked out for us fairly quickly. We didn’t go through too much of a design process. Then I went on set for the film, to shoot the last half of the film, the winter segment, which is where Jonah rips the journal apart, and they have a climactic scene.

I don’t recall the moment when we decided to animate the journal, but I do know that we had a really strong inclination towards that. I always knew that I would get into animation in some form at some point in my career. Jeremiah had worked in animation before, so we both realized that Jonah’s journal should come alive in certain ways. Initially, I was contracted for a month-and-a-half or two months of work, just for the prop journal, and then it turned out to be a yearlong contract to animate Jonah’s imagination.

How influential was Justin Torres’ book for your creative’s process when making the journal, and then working on the animation?

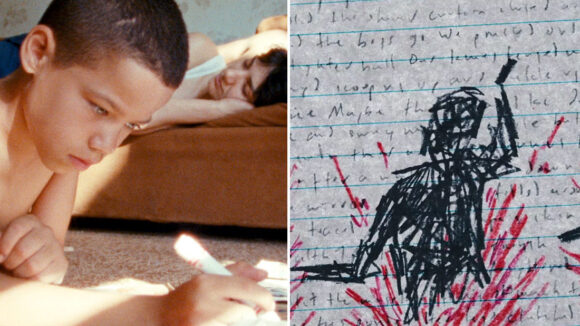

Mark Samsonovich: What Jeremiah had me do was actually create a complete journal. I ended up making more than one journal. Instead of making a few pages that were going to be shown on film, maybe 10 or 15, Jeremiah was like, “No, this must be very authentic, and you need to create the whole thing even if the audience will never see it.” I ended up drawing 100 pages and filling the composition book. The text part of his journal, where he would write down his thoughts, was actually just taken directly from the book. Anytime there were pages in the journal that were just writing, it was me transcribing text from the book. In that way, the book was kind of present in the film, and in Jonah’s writing, but ultimately his drawings and his imagination, the way that they developed and what they represented, was very much inspired by the conversations between Jeremiah and I, and what Jeremiah felt Jonah’s world on paper needed to look like.

Was this the first time you worked in the animation medium professionally? If so, did you find the transition from only illustrating to also animating strenuous or was it a natural progression?

Mark Samsonovich: Yes, this was my first time animating. Previous to this, I had done a 15-second watercolor abstract animation, so I really had essentially zero experience, and definitely no professional experience as an animator. It didn’t feel so difficult. It wasn’t so much a struggle in terms of developing the skill set for it, as much as it was a creative struggle.

Ultimately, there’s about five minutes of animation in the film, but we created double, and with animatics and mock-ups, maybe even three times that. I created thousands of drawings, so the most difficult struggle was on a creative level, as opposed to a technical one. Being that Jonah’s drawings are childlike, it wasn’t too difficult to approach the technical level. It was something I was able to tap into very easily. There were a couple of things I had to learn on the fly, which was almost everything, like how to use software, cameras, and camera gear. All of that I had to learn on the fly.

Jeremiah and I did a lot of testing of experimental types of animation because we needed a very specific mood in the in the paper. For example, we oiled pieces of paper and then we put them on a window and let the natural light hit it from behind, and then we photographed the animation through that paper. The oil and the light gave the paper this texture, and it felt very tangible and very real.

Ultimately, that wasn’t a practical solution, and we ended up finding ways of mimicking [that look] differently. Jeremiah hadn’t animated to this extent before, and we did everything super old school. It was all drawn frame by frame by me. There wasn’t as much difficulty doing it as there was entering into a learning process, and having to be able to adapt as fast as possible, given our time constraints.

What was the process you and Jeremiah followed to decide which moments in the story or which of Jonah’s thoughts would be turned into animated sequences? Or had he already chosen those before you came on board?

Mark Samsonovich: When I started working with Jeremiah on the animation, he didn’t really have the edit down. When I came in, he had the second, incredibly rough edit, and then we pinpointed scenes where we felt like we needed something animated. Then the edit would change, and we would scrap a mock-up for an animated sequence, and we’d replace it with an entirely new concept. That happened on a loop cycle until we refined what the animation needed to be, and where it needed to be, and what part of the story it needed to tell.

Basically, I would create what’s called an animatic, which is a mock up for an animation. They’re like a really choppy version of what the final product will be. It was just to give Jeremiah an idea of what would be happening, how would that look, what motion would look like, in a really fragmented way. I didn’t do any final form animation until near the end. I think we got all the animation done within three to four weeks prior to Sundance. We were super, super tight on time, and we didn’t finalize the animatics until very late in the process. Everything was kind of like a clay mold that kept forming and reforming.

What were the key materials or canvases you used to create the drawings?

Mark Samsonovich: We kept it all authentic to what a child would use, which was pretty much composition paper, computer paper, and colored pencils. That really was it, there were no other materials. It was incredibly low cost in that respect.

Was there a particular animated sequence or drawing that was important to you or a favorite, in regards to what it meant to the story?

Mark Samsonovich: That’s really hard to answer, only because my animations and animatics were constantly being re-contextualized and modified in some ways. I can’t say that there’s any one animation that’s in the final cut that stands out in a particular way to me. If I was to answer that, there’s this one moment in the film where Pops is sitting on the end of the bed and he’s smoking, and as he takes a puff it transitions into animation, and that little segment, that moment where his body becomes filled with this black kind of thing, that’s actually the animation that we used to pitch the producers to get funding for the whole animation. Jeremiah and I picked that in the beginning and decided to animate that as a test, and that’s sort of what won us the funding for the whole animation project. So if I were to choose a favorite, I would say that. Obviously that’s not, in terms of the story, you can’t qualify or quantify how important that is to the story, but I would say that’s probably my favorite animation that I did.

Even though there are only a few minutes of animation in the film, those drawings represent how Jonah expresses his most innermost thoughts and feelings. Did you approach the work with that gravitas in mind?

Mark Samsonovich: For sure. It’s also about expressing things that Jonah can’t verbalize, and expressing things that live-action film can’t depict. It was about expressing something that only Jonah’s mind and his imagination, specifically his illustrated imagination, could express. There’s some really graphic things happening in the animation, and they’re emotionally complex. The overall intention throughout the creative process for the animation was that these were entryways into Jonah’s mind. Jonah being a child, he can’t even necessarily be fully aware of his own reality. These are emotional tapestries, and raw insights into himself. That’s how I would describe them.

Tell me about your regular work as an artist beyond what we see in We the Animals. What is your artistic focus in terms of a medium or a discipline?

Mark Samsonovich: I can’t say that I have a day job, just that I’m a painter. I do illustration and installation work, all around fine art. At the moment, I’m working on some furniture and home goods. The animation thing was completely outside of my comfort zone and outside of my normal work experience. Part of my personality is that I really like learning new crafts and I like trying out things, so although maybe six to eight hours of my day are spent painting, I would say that I spend another six to eight hours a day working on a completely different type of craft, and that’s something that usually cycles for six months or a year at a time. Animation was the thing that held up me for a year, and now in this moment it’s furniture.

Did you enjoy the experience of creating animation? Is it something you would pursue further?

Mark Samsonovich: I would, under the right circumstances. When we began the animation process, I didn’t expect to work on it for as long as I did. We had a contract that kept getting extended, as the process got more involved. I’ve never collaborated with anyone on a creative level prior to working with Jeremiah. Professionally, I’m a painter, and I work alone in my studio. It’s really an intense process to do that with someone for a year. Thankfully, Jeremiah is an incredible person and an incredible collaborator. I had a very positive experience with him. Working with someone on a film, especially in animation on a scale like this, it’s like living with that person, or dating that person. It’s a very intimate process, and if I were to do something like that again, it would have to be with someone I would be happy to work with that intensely.

We the Animals opens in Los Angeles and New York today through The Orchard. It will continue to expand in the U.S. and Canada throughout August and September.