‘A Quiet Place’ VFX Supervisor Scott Farrar On How The Film’s CG Creatures Were Redesigned With Just Two Months To Go

John Krasinski’s A Quiet Place, which has screamed up $100 million in box office through its first two weekends, tells the story of a family struggling to survive in a world now inhabited by alien creatures that hunt by sound. It means the family – Krasinski playing the father and Emily Blunt as the mother – must live in silence as any loud noise will suddenly summon the creatures, with deadly results.

Audiences have been marvelling at the jump-scares in the film, which are very much aided by the long silences and the appearances by the grotesque aliens. But viewers nearly saw something completely different. Just two months before the release of the film, it was determined that the creatures were not scary enough. Artists at Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), which had been working on the cg beasts, had to almost completely reimagine them.

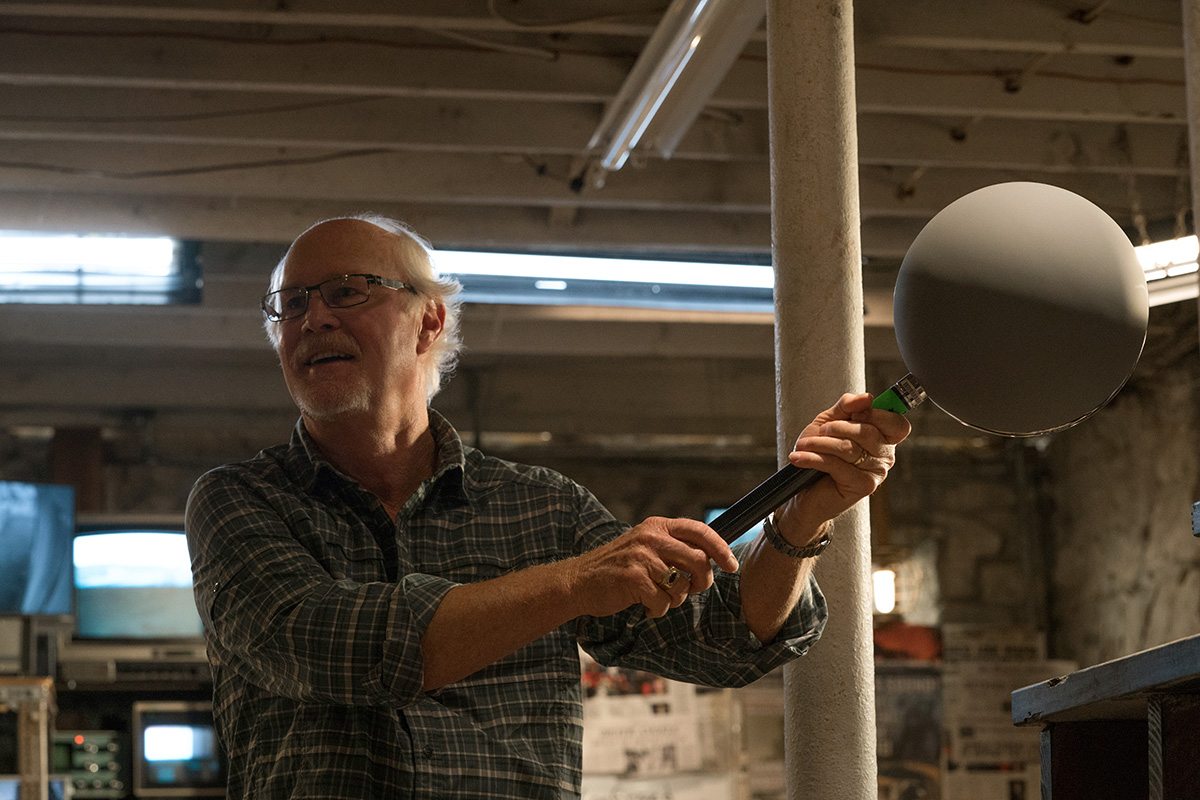

Cartoon Brew talked to ILM visual effects supervisor Scott Farrar, a veteran of the Transformers franchise, about this last minute plan to re-work the creatures, and in particular how the vfx team helped with a number of crucial storytelling points. Note: this article contains several plot spoilers.

Cartoon Brew: Can you talk about the design of the creatures and how that evolved over the production?

Scott Farrar: The big thing that happened was that we pretty well shot the movie and started cutting rough shots in, and the original design of the creature wasn’t scary enough, so we had to do a total redesign, top to bottom, about two months away from releasing the movie. To start with, production designer Jeff Beecroft and the art department came up with the original design. John Krasinski had collected pictures of black snakes with cool looking scales and he had this really great looking prehistoric fish, with sharp, bony exoskeleton-type features that stuck out all over it, and even different types of bats for the way they moved and ran. John felt at the beginning that as it was a super-hearing creature, it would have flaps that opened on its head, and flaps on its face, and flaps on his shoulders, and flaps on his chest, and back, and its sides.

We pushed forward with it, but ultimately we thought people were not going to understand how this creature hears. We had a lot of problems with exposition in the early cuts of the movie, so we all worked very hard to try and make it so that the audience understood things. One thing I said was, ‘If the audience thinks the ears are on either side of head, maybe that’s where the focus should be. Let’s put real ear holes in, so when the flaps open, you really know that that’s how the thing hears.’ A movie has to sell itself in moments. If you see a shot and in that one time you don’t understand the shot, it’s not working. That’s kind of what happened to us. So we completely rebuilt the thing, and we had so little time left. It had to be a complete re-rig, and re-paint, and re-texture, and re-animate. But I had an incredible team of people.

How were you able to turn this around so quickly?

Scott Farrar: I said, ‘Okay. Here’s what we do: we’ll start as soon as we had a figure that actually worked. We’ll put it in the background, where it was dark, or out of focus.’ And we got different shots where it was moving in the background and where it’s harder to see detail. Then as it became more finished, then we could do some of the shots where it got closer and closer. Which means some of the last shots we finished for the movie literally are when it opens up and all the goo comes out. All the simulations of the goo, and the muscles, and everything – that was all the last week. It was really down to the wire. As everything got better and more finished, then we could put him in the closer shots, literally like an actor that doesn’t quite have their make-up on yet.

Was there ever any consideration at the beginning that it be a practical creature, like an animatronic, or done via make-up effects, or as a puppet?

Scott Farrar: That’s a really good question. No, not this case. It was important to John that its proportions not be humanoid. It’s got two legs, and an arm, and a head, and all that stuff, but it had to look different enough where it couldn’t be a guy in a suit. So from the get-go it was going to always be an animated character.

How were scenes filmed on set where the creature had to appear?

Scott Farrar: I had a two or three-hour meeting with John, because he’d never done an effects film before. I said right away, ‘You’re a performance guy, the easiest thing for you is going to be, have somebody in the frame who’s playing the creature. Put him in a tracking marker suit. It’s not going to be motion capture; it’s just going to be a guide for your actors, and your camera people, and then for our animators later.’

Emily was there, too. She came over about an hour or two after we had been meeting for a while. She’s really smart, has a very good intuitive sense about what things work in a movie. I said, ‘So, John’s not used to this stuff. You had guys on the set of Edge of Tomorrow that were playing the creatures that were in some sort of a marker suit. As we get into this, you can kind of talk John through, so he’s comfortable with it.’ Therefore, we had a guy on set always wearing a capture suit going through the motions.

There’s a scene where they’re in the basement and the water is rising and underneath the water you can just barely see the creature. That was such a cool shot, because the guy doing that was over in the corner, and on ‘action,’ when John gave him the cue, he dipped down and turned and went under the water, and made all the water move. There’s a plastic water jug, and a chair, and something floating, and it made them move. So, I said, ‘Ah, if we can just replace him and put our creature in as it goes down, and keep all the water movement, and all the bobbling objects in the surface, it’s going to be really, really good.’ That’s what we did, and it looks so good, because it’s the real water.

One of the challenges must have been when the camera goes close up on the creatures’ ear drums, just for the high amount of texturing and level of fidelity in those scenes. Was that particularly hard?

Scott Farrar: Wasn’t that good? I thought it looked so cool. I was just really pleased. I kept trying to say to John, ‘You’ve got to have the goo, and you’ve got to have all the little ear worms, the little pieces of chicken fat that are wiggling, and squishing around, and all of that stuff.’ I wanted it to look real, like medical in nature, as if you’re looking in on open guts.

There’s a scene where the kids are stuck in the silo and nearly drown in the corn when the creature arrives. How did that come together?

Scott Farrar: I think what’s fun about the silo scene is that that’s an old-time effects gag. That’s just a big, rubberized diaphragm thing with a hole in it. It’s a membrane that’s stretched across the bottom there, and it’s all a plywood platform underneath, with a little hole that the kids can slip down through. There’s only a small layer of corn. It looks like it’s really thick, but it’s maybe six inches, and it all drains out. There are shots, by the way, where the rubberized membrane shows, so we had to put extra corn in. One of our jobs was to clean all that up, because it gives away the trick.

In that scene there was something else we had to slap together, too. They weren’t quite prepared, so my experience in trying to do quick and dirty things in visual effects came through. They needed to have the creature hitting the door, and then that panel drops down from the top of the silo. They said, ‘Well, we can do it without the door.’ I said, ‘You have got to have the door. Look, here’s what we do. I need 20 minutes.’ We’d actually done this in past in our model work where we did a lot of stuff with heavy duty foil. So we took the panel, hogged out the center area, covered that with heavy foil, glued it on and painted it the same color. You couldn’t tell. Then we made a little rig, a mandrel, which was the same shape as the creature’s claws. And we put it onto a fancy green rake once they put the whole thing together with C-stand arms. So, with that they could have the door there and have the rig come down through it right next to the kids.

It was important for framing because then you knew where to aim the camera, because the claws would actually come through, and the camera person could actually see the torn holes. Then they could frame for the kids’ heads and the corn that’s flipping around. Then we replaced the green with real claws later. So, that was very last minute stuff, but that’s how movies get made.