4 Steps Sony Imageworks Took To Animate The Sardonic Pawny From ‘Men In Black: International’

F. Gary Gray’s Men in Black: International features a brand new character in the MIB world: Pawny, a tiny alien who, after a massacre in Marrakesh, appears to be the last survivor of his kind.

Voiced by Kumail Nanjiani and crafted by Sony Pictures Imageworks, the large-headed, small-bodied, and often sardonic creature interacts directly with the film’s main characters, Agent H (Chris Hemsworth) and Agent M (Tessa Thompson).

Here’s how, step-by-step, Imageworks went from animation tests to final Pawny shots.

Step 1. Using concept art and the voice actor as leaping off points

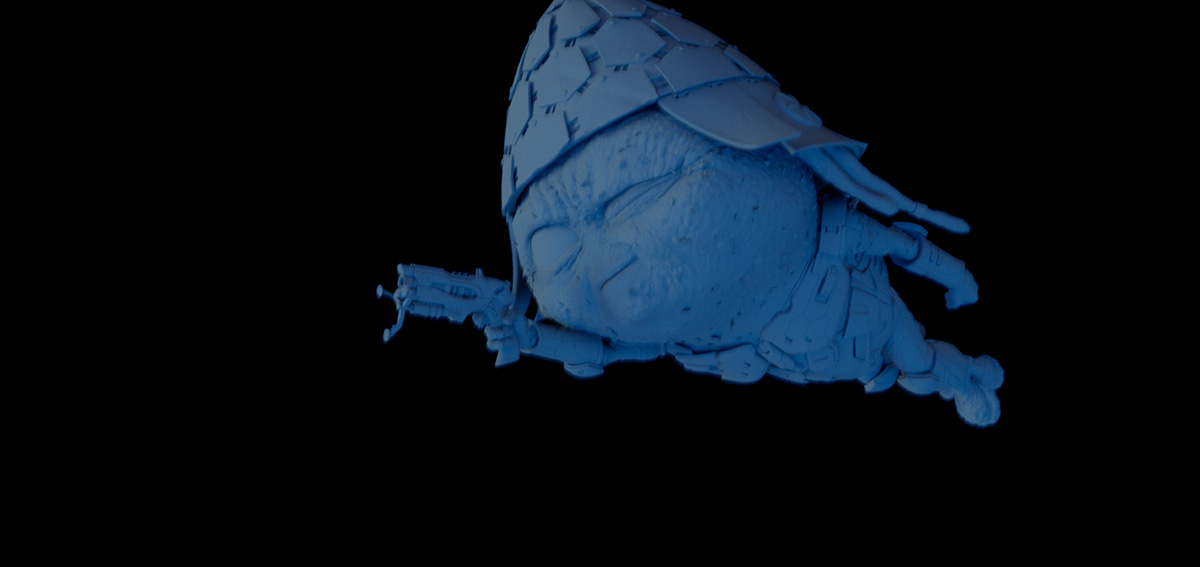

Imageworks launched into modeling Pawny after firstly consulting production concept art. “One concept that really resonated with everybody,” outlined animation supervisor Craig McPherson, “was Pawny as this kind of battle-weary bullfrog, a tired old general soldier who’d seen it all and was ‘over’ it. He had these great half-lidded eyes, and a non-plussed expression on his face. Everybody just really enjoyed that image.”

The team also considered, of course, the particular traits of Nanjiani, who is well-known from the tv show Silicon Valley and the film The Big Sick. The actor was not on set – a 3d printed model of Pawny was used for stand-in and lighting reference – but the animators began shaping the performance with Nanjiani’s work as reference. “He’s very sardonic, he’s sarcastic, he’s super witty, and dry,” said McPherson. “Then when we started hearing the lines that were coming in and the vocal performance, we knew we had our character right there.”

“Our next step,” added McPherson, “was to go a little bit deeper and try to really create who this guy is. So, we looked into a backstory for Pawny, and we came up with this idea that he’s this intergalactic assassin and weapons designer. We went pretty deep into finding out who he was. A lot of that you’re not going to see on the screen, but it just helps the animators all get a frame of reference and get grounded into who he is.”

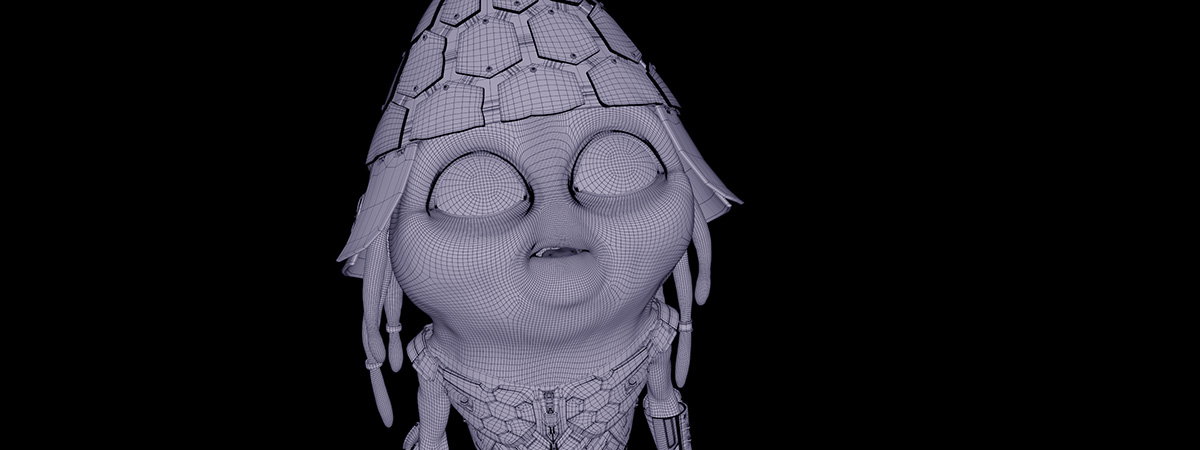

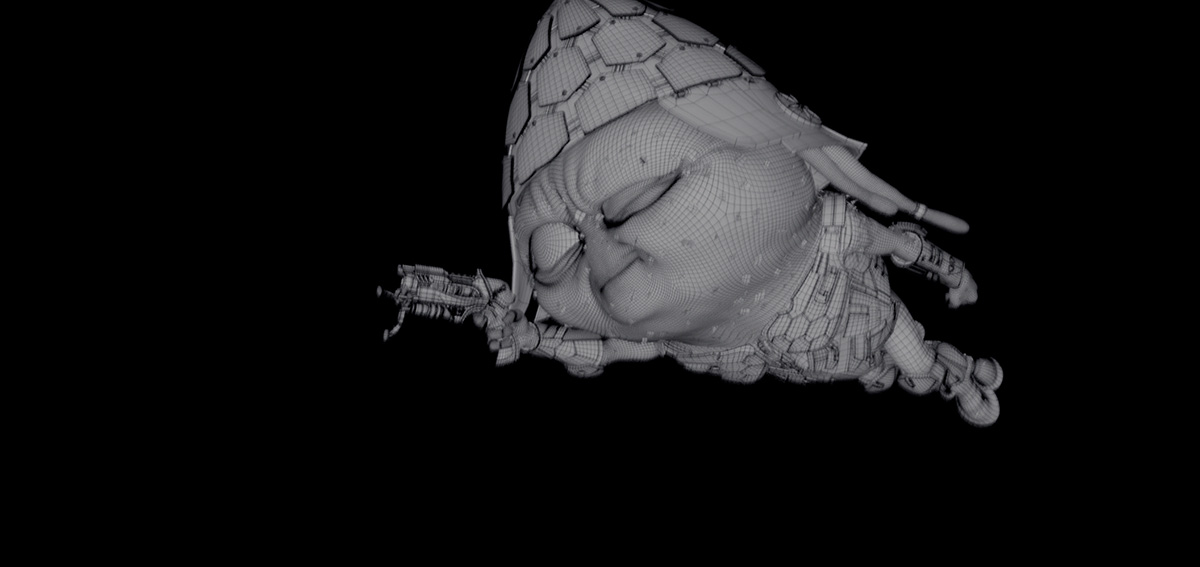

Step 2. Animation tests

With an early model of Pawny, Imageworks’ animators set to work on animation tests. This started with poses, including putting the character in heroic positions and action beats. “Then we moved pretty quickly into walks and run cycles because that informs us a lot about how the body will deform, how the muscles and the skin are going to react, and how far we can push his poses,” explained McPherson.

Since Pawny has a large head and small body, the team realized he might have a hard time keeping up with the human characters in the film. “We did some running tests and the speed at which he would have to run to keep up with a human, even walking, would be just almost comical,” said McPherson. “But, luckily, the filmmakers decided that he was going to ride in the pocket with the agents all the time, so that kind of solved that problem for us.”

Pawny’s fighting abilities were an important part of the character, so Imageworks did some tests where he uses his sword to mock-fight and his blasters to fight off other aliens. “There was also his grappling guns that he uses in the Paris portal room scene at the end of the film,” added McPherson. “We had done some initial testing where he would jump around with those, and that would have been quite a fun thing to explore, but ultimately that didn’t make it in the movie.”

Step 3: Facial and body performance

Nanjiani did carry out some head-mounted facial camera capture for Pawny, but this was not something Imageworks used directly. What they did use it for was reference (along with the actor’s previous tv show and film work). “We used a lot of that reference to enhance and alter what our character design was going to look like and build our face shapes around that,” said McPherson. “Pawny’s quite graphic looking, so his eyes were very simple and really beautiful. We had to add a lot of anatomy to him because Kumail’s just got these incredible expressive eyes.”

From there, animators spent time further exploring Pawny poses, taking into consideration his slightly unusual head and body shapes. “He’s quite limited in where his arms can go,” noted McPherson, “and his head is really big, and he essentially has no neck, which means that his shoulder work is really hard too. For example, it was really hard to make him shrug, which is what we just wanted to do all the time. But we didn’t have the anatomy to do it, so we had to find other creative ways.”

Those other creative ways came from looking closely at how Nanjiani performs, which McPherson says often came through his eyes and brows. “He’s not a very physical actor, and we played Pawny a little bit similarly. We tried to sell all of his expression work in those big expressive eyes that he has, since we weren’t able to rely on his body language as much as we would with a different proportioned character.”

Oftentimes, Pawny exhibits a sardonic, deadpan look. This was something McPherson had seen very clearly from the concept art, but it was a harder thing to make happen as a cg character. “It’s really easy in 2d,” he said. “You can just make a beautiful straight line of the lids, and bury the pupils halfway into the lids, and you can get that look really nicely. It’s really hard in 3d, especially when you’ve got big bulbous eyes like Pawny has, so we spent a lot of time studying Kumail’s expressions and just refining our face shapes. Once we had that pose working, we knew we could move into the shots and nail that character.”

Step 4. Animator video reference

In addition to voice-over reference, animators used their own video reference for Pawny shots. Part of that was to ensure the locomotion of the character remained natural, rather than designed, said McPherson. “I encouraged the animators to shoot multiple takes of their shot even before they started thumbnailing, or before they started trying to pose the character, just to make sure that we got that spontaneous feel for him.”

“We had animators who would shoot nine takes of a shot, cut, and send them all to me,” continued McPherson. “We could cut them all in, look at the sequence with everybody’s takes, and then just judge how continuity was working between the shots and to make sure we have the right emotional tone work between them. Then, once we chose takes, we would have the animators go and block that out.”