3 Key Ways That Europe’s Feature Animation Scene Differs From The U.S.

The differences between the European and American feature animation scenes were never more apparent than when I attended Cartoon Movie in Bordeaux, France last month.

Fifty-five animated projects were presented at the pitching and co-production forum, now in its 19th year. Films were presented in all stages of the production cycle; some projects were in the early concept stages, others further along in development, and some were deep into production.

Some of the differences are fairly obvious. For example, every European producer resisted the temptation to add a talking piece of poop to their trailer. But I also observed some deeper fundamental differences between how Europeans and Americans approach feature animation filmmaking. Here are three key ways that the playbook of European producers differs from their American counterparts.

1. There is no culture of secrecy surrounding animated features

Possibly the most surprising thing about the European animation scene is its openness. European filmmakers pitch their concepts in front of hundreds of attendees, and increasingly, they have started releasing their Cartoon Movie concept and pitch trailers online after the event. Cartoon Brew, in fact, premiered three such trailers this year: Kensuke’s Kingdom, Icarus, and Wolfwalkers.

Coming from the United States, where film studios protect the plots to animated features like Trump protects his tax returns, it’s something of a novelty to see European filmmakers openly sharing their film ideas, years before the films are actually made.

In part, it’s done out of necessity; in Europe, big entertainment conglomerates rarely fund entire films as in America. Budgets are cobbled together with financing from different countries, with various producers chipping in parts of the budget, along with presales to distributors in different countries. There’s less chance of finding production and distribution partners unless others in the business know about the project. It’s no exaggeration to say that for many European films, the process of lining up the funding often takes longer than the actual production of the film.

But there is also less need for secrecy because European features, at their best, aspire to an auteur model that allows the film to bear the tonal imprint of its creator. You could pitch Alberto Vázquez’ Unicorn Wars, Tomm Moore’s Wolfwalkers, or Rémi Chayé’s Calamity, A Childhood of Martha Jane Cannary, and yes, another studio could superficially copy all of the same elements, but in the end, none of the copycat films would ever be the same as a film by Vázquez, Moore, or Chayé because they put so much of themselves into their ideas.

2. Lower budgets create opportunity for graphic diversity

Most of the films pitched at Cartoon Movie were in the ballpark of 3 to 15 million euros. That amount is significant enough to assemble a solid crew and develop a custom-pipeline for production, yet not so much that it makes risk-taking impossible.

By contrast, big-studio American feature animation budgets range from $60-200 million. At that cost, risk-taking is no longer the priority; the goal is to reach the largest audience possible and recoup the investment.

Graphic diversity means a lot of different things. Among the trends at this year’s Cartoon Movie was stylized cgi projects, among them The Siren, Charlotte, A Skeleton Story, Fox and Hare Save the Forest, The Prince’s Journey, and Zombillenium. The move toward stylized cg is a good lesson learned by European producers, who in the past have often run into trouble when they’ve tried to replicate Pixar/Dreamworks-level graphics on a fraction of the budget. Stylizing the look of the production results in something that stands on its own, and can’t be compared unfavorably to slicker American productions. Stylized cg features are being made successfully in Europe and beyond, and some excellent pieces have been completed in recent years, including Adama, Louise by the Shore, and Seoul Station.

Graphic diversity also means that hand-drawn animation is alive and well in Europe. There is no single technique that dominates the European animation scene as here stateside. Below are just a few of the teasers for predominantly hand-drawn projects pitched at Cartoon Movie this year:

Going back to the auteur concept, European producers often allow the director to determine the right technique for a film. The lower the budget, the more experimental things can get, such as the pitch for The Fantastic Voyage of Marona by Romanian director Anca Damian (Crulic: The Path to Beyond, The Magic Mountain). Her project mixed all kinds of techniques, including digital 2D animation, painting, cut-out, and cg to tell its story of a dog remembering its different masters.

3. Real life as inspiration

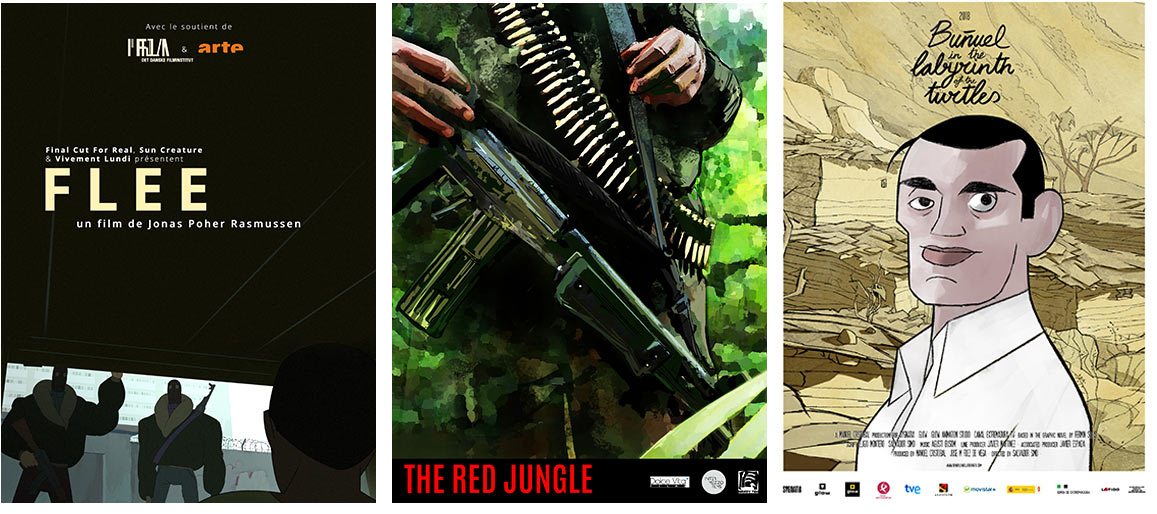

The amount of projects at Cartoon Movie based on real-life figures was staggering: Aurelien Froment’s Josep (a hand-drawn film on the life of cartoonist/artist/Spanish Civil War refugee Josep Bartoli), Bibo Bergeron’s Charlotte (toon-shaded cg film about painter Charlotte Salomon who was killed by the Nazis at the age of 26), Juan Lozano and Zoltan Horvath’s The Red Jungle (stylized video footage with animation elements based on the 2008 death of FARC guerrilla commander Raúl Reyes), Salvador Simó’s Buñuel in the Labyrinth of the Turtles (hand-drawn film based on an early project in the career of Spanish film legend Luis Buñuel), and Johan Poher Rasmussen’s Flee (hand-drawn documentary about an Afghan immigrant in Denmark).

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. There were plenty of pitches based on historical figures or events. Those projects include Jan Bultheel’s Canaan, Sepideh Farsi’s The Siren, Michaela Pavlátová’s My Sunny Maad, Rémi Chayé’s Calamity, A Childhood of Martha Jane Cannary, Jung Henin’s Single Mom in Korea, and Manuel H. Martin’s Awakening Beauty.

There aren’t many comps that European producers can point to as successful examples of films rooted in historical fact. Over and over, I heard producers highlight two films—Waltz with Bashir (an Israeli production with European co-producers) and Persepolis. They are the existing success stories driving the trend: both films screened at Cannes and were nominated for Oscars (Bashir in the foreign language category), and both films performed well financially.

This is the pace of how trends develop in animation. Both of those films were released a decade ago, and only now have other producers been able to convince financiers and distributors that there is a demand for mature animation targeting young adult and adult audiences. The variety of projects on display suggests that there’s no turning back: European producers are developing new audiences with this latest wave of films, and if even a few of them achieve success, expect further efforts in this direction.