Chuck Jones, The Beatles, And The Power Of ‘Yes’: A Creative Lesson

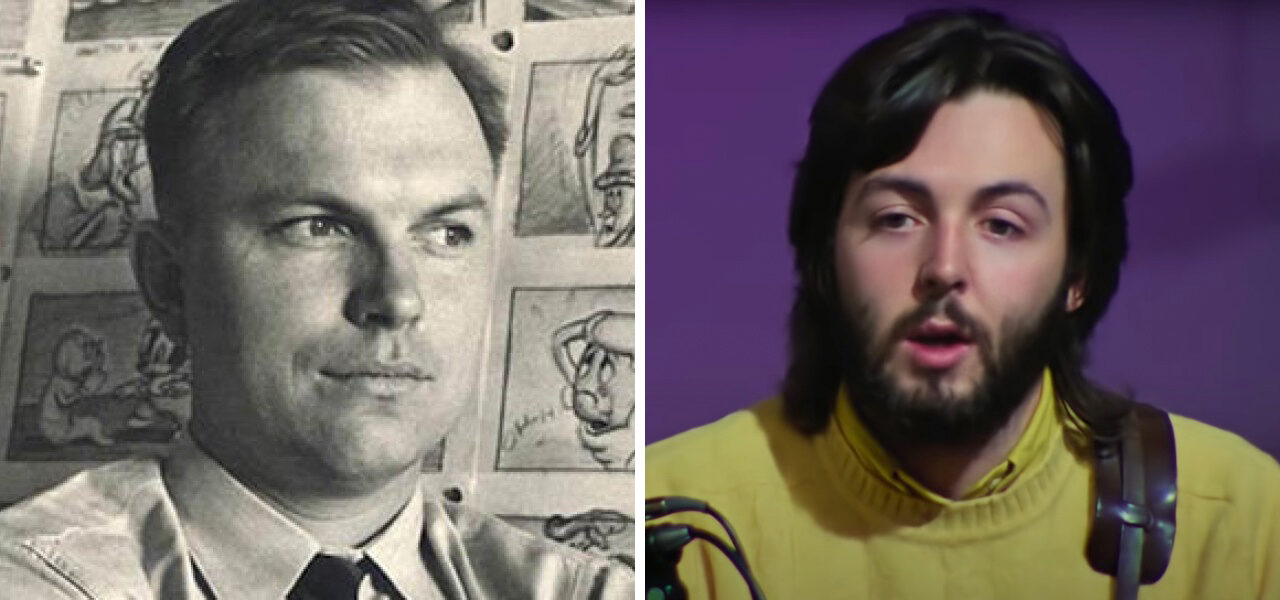

What do Chuck Jones, Paul McCartney, and British consultancy Fluxx have in common? They all take a stand against the word “no.”

Somewhere deep into Get Back, Peter Jackson’s mammoth presentation of archive footage of Beatles rehearsals, George Harrison drops a negative: “I think it’s awful,” he says of an arrangement of the song “Don’t Let Me Down.” John Lennon and McCartney retort: “Well, have you got anything?” and “You’ve gotta come up with something better.”

There are other moments like it in the documentary, when a tetchy bandmember dismisses a creative suggestion from another. But more often, we see them building on each other’s ideas, testing them out and embellishing them under McCartney’s guidance.

This approach — elaborating on ideas, not rejecting them — is a central pillar of creative leadership, argues a Fluxx consultant in a Medium post about Get Back (which is streaming on Disney+). “When someone suggests an idea, plays a note, says a line, you accept it completely, then build on it,” writes Tom Whitwell of that scene in the documentary. “That’s how improvisational comedy or music flows. The moment someone says ‘no,’ the flow is broken.”

We’re bringing this up here because it aligns almost uncannily with one of Chuck Jones’s main precepts. In his memoir Chuck Amuck, the animation legend describes the “‘yes’ sessions” he would hold to develop stories. These sessions followed one rule: no one could say “no” or any other negatives, such as “I don’t know” or “I don’t like it.” Wrote Jones:

Anyone can say “no.” It is the first word a child learns and often the first word he speaks. It is a cheap word because it requires no explanation, and many men and women have acquired a reputation for intelligence who know only this word and have used it in place of thought on every occasion.

He adds:

Of course, all story ideas are not good or useful, and if you find you cannot contribute, then silence is proper, but it is surprising how meaty and muscular a little old stringy “yes” (which is another name for a premise) can become in as little as fifteen or twenty minutes, when everyone present unreservedly commits his immediate impulsive and positive response to it.

Fluxx’s Whitwell takes other creative lessons away from Get Back, among them the importance of embracing happy accidents — as when Lennon misreads one of Harrison’s lyrics, improving it in the process — and of “pretending to be someone else,” for example by playing another band’s songs.

Many of these lessons apply to animation, as anyone who has painstakingly copied out the drawings of their favorite artists could tell you. Flip it around, and it becomes clear that animation production holds lessons for creative people working in other disciplines, too. Now all we need is an eight-hour documentary depicting the entire production of an animated film.

Here is an extended essay from 1958 by Jones about the importance of nurturing ideas in their formative stages:

.png)