The Stories Behind 3 Animated Documentaries: ‘Carlotta’s Face,’ ‘Egg,’ ‘Travelogue Tel Aviv’

A century after Winsor McCay animated the sinking of the passenger ship Lusitania – an event no cameras had filmed – the genre heralded by his film is coming of age. Animated documentaries have proliferated in recent years. This is true of feature films, including chiefly live-action works that deploy animation in illustrative segments.

But the trend is also clear in the world of shorts. Faced with an uptick in submissions, festivals are increasingly recognizing animated documentaries with panels and sidebars; Liverpool, England now has a festival dedicated to the genre, Rising of Lusitania – AnimaDoc Film Festival. Its definition is still in flux, as filmmakers and audiences try to square animation’s “artificiality” with documentary’s “reality.” If this tension exists, many animated documentaries make a virtue of it, harnessing their medium to show aspects of true stories that are beyond live action’s reach.

Cartoon Brew picked three short animated documentaries from the current festival circuit, and spoke to the filmmakers about how they came to be made.

Carlotta’s Face (Valentin Riedl & Frédéric Schuld, Germany)

As a neuroscientist, Valentin Riedl already knew about face blindness when he discovered Carlotta’s art. Though cognitively unable to recognize faces (including her own), Carlotta has produced over a thousand self-portraits, which she draws while touching her features for reference. After coming across these works, Riedl met Carlotta, who struck him as “special”: “I never wanted to do a scientific film about the condition, but was most intrigued by Carlotta as a person.” He ended up conducting many interviews with her over two years. It occurred to him that animation could go some way toward capturing her unique way of seeing.

Riedl approached Fabian&Fred, a German studio with experience in both animation and live-action documentaries. He had encountered them through a scholarship program run by Wim Wenders (who mentored the team throughout the production of this film). Producer Fabian Driehorst was keen on the project: “Documentary is often very contrary to animation in terms of planning and execution, but at the same time, it can be the perfect match for the story… [Animation] can add ‘auteurship’ to the documentary, which makes it authentic.”

With director Frédéric Schuld, Riedl boiled his hours of interviews with Carlotta down to a five-minute audio track. This provided the basis for the storyboard and layouts. Riedl, Schuld, and Driehorst brushed up on films and artworks that deal with similar subjects. Inspirations include Isabel Herguera’s Gallina Ciega and the documentary Notes on Blindness, which was released as both a film and a virtual reality experience.

Carlotta uses a distinctive printing technique, which Schuld aimed to replicate digitally; in TVPaint, he custom-made brushes based on scans of her self-portraits. The film shows no faces – just a red-headed creature wandering through semi-abstract landscapes, whose scattered forms reflect Carlotta’s perception of people’s features. Her reflections on face blindness are read out in voiceover. While Carlotta stayed away from the production (by choice), she loved the finished film, which she watched dozens of times in one night.

The filmmakers received funding from the German government, but the studio itself had to supply half the budget. They didn’t make Carlotta’s Face with a specific audience in mind, and they were surprised when it ended up being distributed to schools in German-speaking countries. “It was intriguing to see how children immediately grasped the impact of this condition on Carlotta’s social life,” observed Riedl. “It is hard for her to make friends, and she doesn’t have a partner.” In addition, the film has been paired with features in theatrical screenings.

Carlotta’s Face preserves something of Carlotta’s anonymity. However, the artist will take center stage in Lost in Face, a forthcoming feature from the same team which combines animation and live action to tell her story in detail. “Her life will be depicted with real footage, yet her inner voice, her unconscious, and her way of seeing the world will be translated into an animated world,” said Riedl. “I think Carlotta’s condition and subjective view of the world is a perfect story to be told in hybrid form.”

Egg (Martina Scarpelli, France)

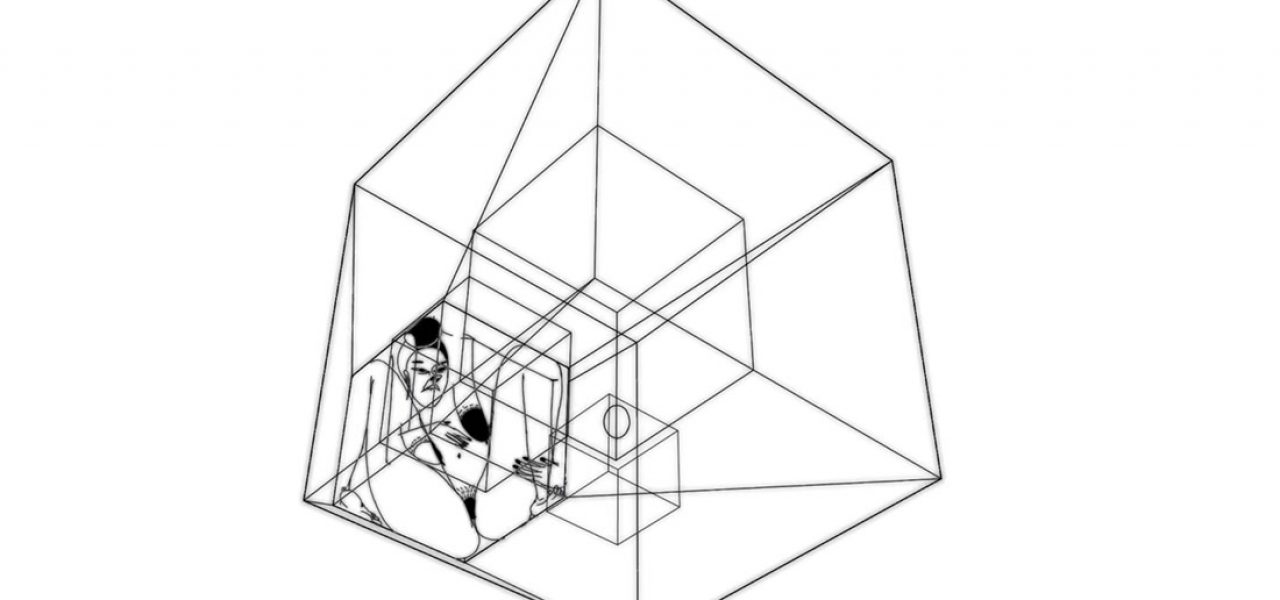

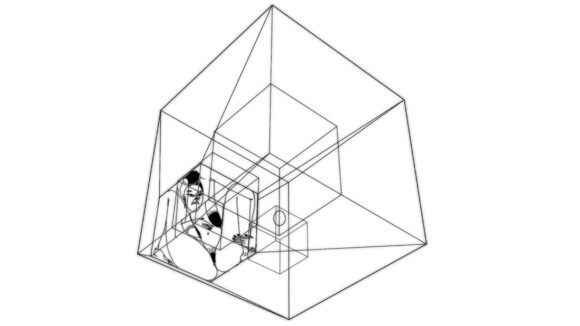

On first viewing, Egg doesn’t seem like a documentary. In voiceover, an anonymous woman recounts her obsession with an egg in her kitchen. This scenario is depicted in highly stylized monochrome visuals, in which forms are reduced to their geometric essence. It becomes clear that the woman is describing her struggle with anorexia – a disorder, she tells us, which is “about reaching the perfect shape.”

The film plays like a twisted, quasi-erotic fantasy. For Martina Scarpelli, though, there is nothing unreal here: “It’s me. It’s my story.” At a workshop in 2013, she was asked to write about a turning point in her life, and this is what came out. “But I felt very uncomfortable reading it to others, so that first draft of the film was very abstract.” Three years later, she settled on a way to stage the narrative, and started animating. “It is still uncanny and quite disturbing, but it became more personal, less serious, and a bit silly.”

Scarpelli has watched many documentaries about eating disorders (ED), and they tend to disappoint her. “I get annoyed when girls with ED are portrayed as victims… You often see the disease, and not the person. That is a classic, because anorexia is scary for ‘the others.’” Egg tries another tack: we come to see how the woman’s disorder stems from a sense of control, however misguided. Scarpelli’s reference points were fiction films about obsessive desires, like Peter Foldes’ Hunger and Marco Ferreri’s La Grande Bouffe.

Noting that other films have already stated the facts about anorexia, Scarpelli felt free to take a new approach, exploiting her medium to the fullest. “Animation is constructed. It has distance from reality that gives the audience a chance to understand what is happening to the protagonist of the story, mentally… I was able to use space and volume as active elements of narration. I don’t know how you define a documentary, but I am happy to see people sacrificing their need of realism for the sake of enjoyment, engaging with the film.”

Nevertheless, Scarpelli saw the advantages of presenting Egg as a documentary. This enabled her to make it as part of the Anidox Residency in Viborg, Denmark. She received accommodation for a year, the use of a studio, a small grant, and help with promotion. Adding the “documentary” label to her pitch opened up new avenues of funding, and eased the film’s entry into documentary festivals like Hot Docs.

The film’s truthfulness has touched people, reaching a wider audience than Scarpelli had expected. “We ended up showing the film to kids, medical festivals, conferences, and eventually also to ED patients. I never thought people with ED would care about it. If you asked me back then to watch a film about my illness, I would have said no. But people proved me wrong.”

Travelogue Tel Aviv (Samuel Patthey, Switzerland)

While studying animation at the Lucerne School of Art and Design, Samuel Patthey was given the chance to spend a semester at a partner school abroad. He went for Tel Aviv: “I knew I’d have fun there, and it would be a real change of scene.” His course at Shenkar College encouraged him to hone his drawing style. He spent six months observing the city’s life – its nightclubs, weddings, religious gatherings, etc. – and returned to Switzerland with hundreds of pages of sketches.

In Lucerne, Patthey decided to turn the drawings into a film. He successfully pitched the idea at his school. “It was a way to re-analyze what I’d lived over there, which was very intense and interesting.” He had form in experimental animated documentaries: his earlier short Hangover, Cardboard & Chacha was inspired by Boris Mikhailkov’s photos of the former Soviet Bloc. For Travelogue Tel Aviv, he also studied other works of animated reportage, such as Karolina Glusiec’s Velocity and Isabel Herguera’s Ámár. He contacted those two filmmakers to ask how they had approached their subjects.

Armed with his myriad drawings, Patthey tried something unorthodox. “I printed these sketches out as tiny panels, which I put up on the wall. I then tried to group these according to the subjects I wanted to touch on in my film. Once I’d chosen these subjects, I took the sketches and put them on a timeline, following my intuition, my sense of the place.”

This timeline served as a kind of storyboard, so Patthey skipped to the animatic stage. He even returned to Tel Aviv to record ambient sounds and do extra sketches, as he “really wanted it to be as authentic as possible.” He argues that his choice of medium let him witness things that a live-action crew could not: “I find that people react differently to a camera than to a sketchbook.”

The film is a string of vignettes, and Patthey’s teachers initially worried that it would be too loose. They convinced him to introduce himself into the scenes, his presence serving as a kind of through line. The cartoon Patthey pops up here and there, often smoking but never speaking. “The main character is the city. I really didn’t want to intervene in these crucial scenes which were doing their best to depict Tel Aviv.”

The visuals sometimes push into abstraction, which Patthey compares to fiction. “The style of drawing I used, very simple and stripped back, leaves a lot to the imagination. I find it very important to interrogate the viewer with these blank spaces, these simplified lines.” He acknowledges that the notion of an animated documentary troubles some; although he pitched Travelogue as a doc, one festival didn’t accept it as such. But most did, and the film has won several prizes in documentary categories. Patthey is now applying the same approach to a film about a retirement home.