Fragile Figures: BluBlu Studios On The Haunting Animated Vignettes Of ‘Porcelain War’ Documentary

The fantastical porcelain figurines of Anya Stasenko and Slava Leontyev are a tiny part of co-director Brendan Bellomo and producer Aniela Sidorska’s documentary Porcelain War – winner of the 2024 Sundance Film Festival’s U.S. grand jury prize award for documentary.

The film features three two-minute vignettes where small ceramic figures, seated in woodland settings, appear to come to life with hand-painted illustrations that flow across their surfaces. The animation, created at BluBlu Studios in Warsaw, Poland, plays in counterpoint to the story of the figurines’ creators – Anya and Slava – and the film’s cinematographer Andrey Stefanov, in present-day Ukraine.

From the outset, Bellomo and Sidorska planned to use animation to showcase the beauty of the couple’s art. “We had a close collaboration with Brendan [Bellomo] and Aniela [Sidorska],” noted BluBlu Studios creative director Jed Skrzypczyk. “Aniela is Polish. She left Poland when she was young, but she has a strong connection to Polish animation. Back then, Brendan and Aniela had met Anya and Slava and they were trying to figure out how to tell their story as an animated film.”

In February 2022, Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine. The filmmakers reached out to the artists, but Anya and Slava decided to continue working in their rural home, while Slava and his friend Andrey assisted the Ukrainian resistance. The documentary also shifted focus. “They decided to create a movie together,” said Skrzypczyk. “But Brendan and Aniela wanted to keep the animation component to tell a story of the past, present, and future through Anya’s work. It is deeply connected to Ukrainian culture, and speaks volumes about their situation in Ukraine.”

Cartoon Brew spoke with BluBlu’s Skrzypczyk and animation lead Michał Machowina about the creation of the film’s haunting animated vignettes.

Cartoon Brew: How did the filmmakers select the ceramic pieces for animation treatment?

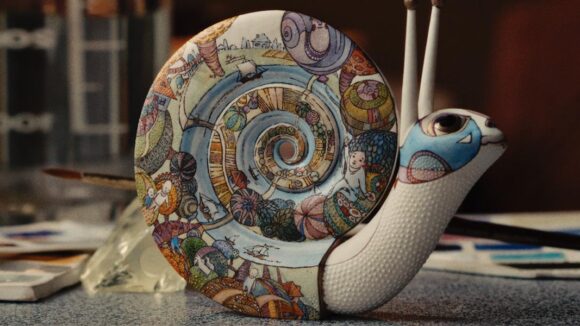

Jed Skrzypczyk: They chose the figurines as the film progressed, based on their editing, and what Anya was creating at the time. That was my impression. One of the ideas was to introduce all of the figurines, and do animation on different figurines going from one to another. Eventually, we ended up working on the snail, then the owl, and Pegasus because they felt that was a good summary of the film.

How did you figure out your animation process?

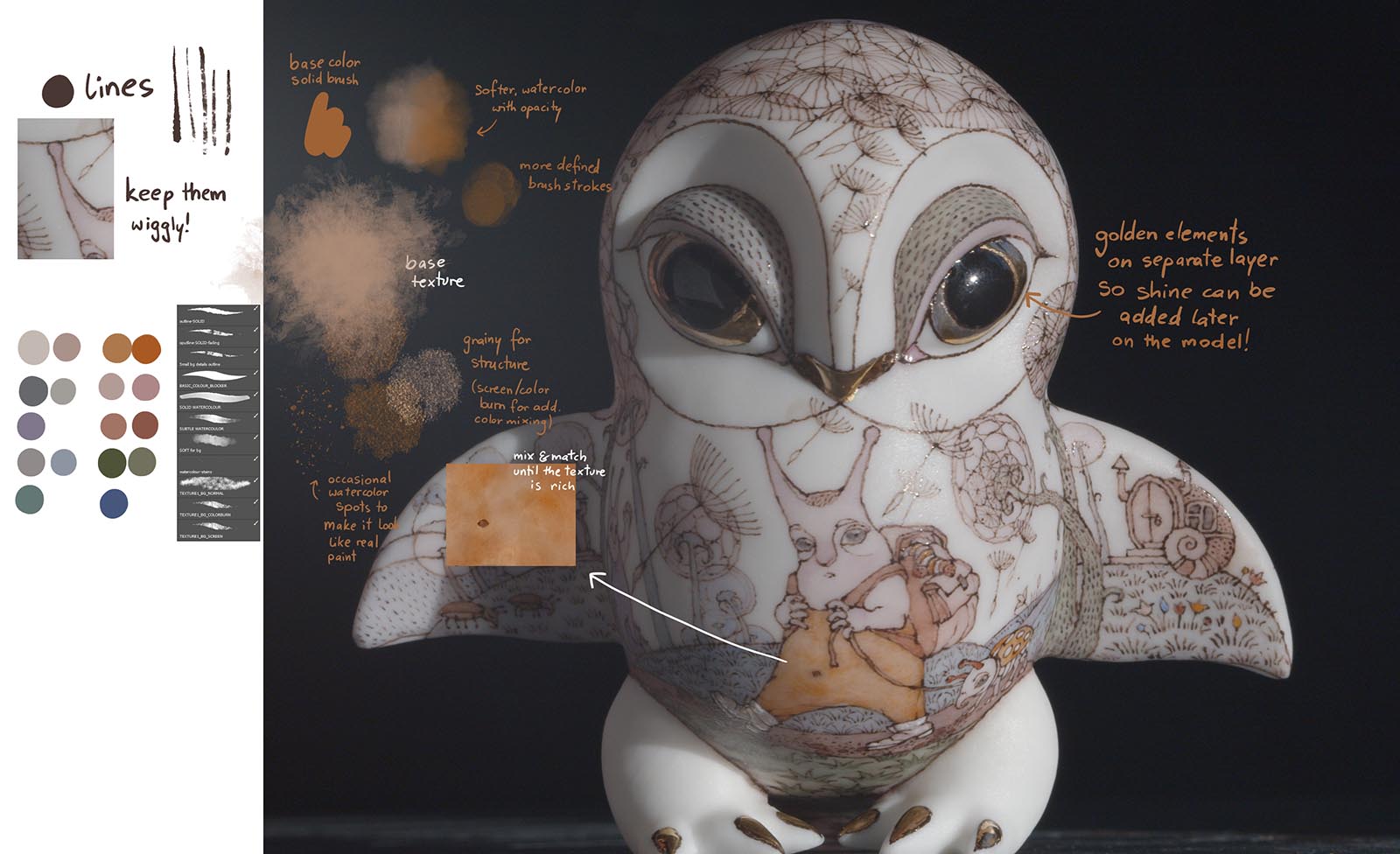

Michał Machowina: We started working on the animation a long time before we knew what the figurines were going to be. At first, we had only photos and one very rough scan of the owl. We started all our research and development on that very rough scan. It wasn’t a professional scan. It was [made from] phone-made pictures shot in their backyard. But we used that for R&D and to determine how to do the work.

Skrzypczyk: When we started animation, on the snail, they sent the snail from Ukraine to the United States to scan it. They gave us a rough scan and high-res pictures. Based on the high-res pictures, we redrew every detail from the figurine. It was so small, we had to be very careful in figuring out the style and replicating Anya’s style. From the scans, Michał and I tried to figure out how they should shoot all the figurines and we made a rough animatic. Based on that, Slava and Andrey shot the figurines. And then, we began full animation on a 3d model that replicated the real figurine.

Machowina: The shots were not a 1:1 match of our previs, but they tried very hard to replicate our camera movement. Also, we didn’t make the entire shot at BluBlu. We outputted only the textures. We needed the 3d model to test our animation and to create camera movement. But cg supervisor Quade Biddle, an Australian vfx artist, took care of compositing and 3d rendering. He managed all the 3d rendering, all the bumps and reflections on the textures. That’s what made the figurines look so real because all the little light reflections and details were spot on.

How did you create the translucency of paint sliding across the porcelain?

Skrzypczyk: We tried to replicate Anya’s style by choosing the right brushes and colors and testing the animation. That R&D process was two or three months. We sent tests to Aniela and Brendan, and they passed those on to Anya and Slava to see how they felt. Replicating Anya’s style took some work. The biggest challenge was to create completely new illustrations for the animation because Anya is an incredible artist in creating all her beautiful paintings. We had to imagine, for example [on the owl], how a subway [in Kharkiv] could look like in her style. We thought maybe there could be underground tunnels, with [shell-less snail] people sitting there with ladders. Anya thought that was amazing, and she gave us the green light to work with that.

In motion, one can see 3d relief as the animation flows over little bumps of paint – was that derived from Anya’s brushwork?

Machowina: Yes, because when Anya paints the figurines, she makes little dots with her brush. On the very high-res pictures, we could see that the illustrations on the figurines weren’t flat. That was an important detail. We exported bump maps for those little spots to prepare them for Quade’s postproduction.

The animation on the snail is complex – a little boy with his balloon jumps across a river, which turns red, as warships sail in – how did you choreograph that?

Machowina: It wasn’t easy. We prepared those thoroughly with a ton of previsualization and very detailed animatics. For example, with the boy playing with the balloon, and the ships on the river – we didn’t work on that shot as one long sequence; we divided it into individual parts, with specific movements.

Skrzypczyk: We also had to keep continuity between shots, because we had different artists working on different characters, but they all had to integrate. We storyboarded each piece, taking inspiration from Anya’s work, creating small scenarios. We blocked out the actions of the characters, and we cut them into specific shots.

Did the directors give you carte blanche to interpret imagery from Anya and Slava’s voiceover narration?

Skrzypczyk: We had a lot of discussions with Brendan and Aniela about Anya and Slava’s situation, and what the figurines were supposed to mean. We received the painted figurines, their voiceover, and a transcription in English. From that, we tried to figure it out. As Polish people, the war in Ukraine also affected us in so many ways. So we were connected, and we tried to use that in our animation while trying to be as descriptive as possible. Anya and Slava in these moments were telling [stories] like a fairy tale. The thoughts and ideas came as we were drawing the storyboards. When the river changed into blood, we were scared that maybe was too much, but Aniela and Brendan said, ‘Yeah, this is powerful, we can definitely use it.’

How did Anya and Slava react?

Skrzypczyk: Brendan showed us a short recording of Anya and Slava when they first saw our animation. There were gasps and smiles and laughs. That was when we knew that we were going in the right direction. And then, at Sundance, I had the opportunity to talk to Anya and Slava. Anya told me this was how she dreams about her figurines. That’s how she imagines them, moving, being alive.

The final animation of Pegasus – with a Ukrainian lady weaving a rug from the tragedy of destruction – is particularly charming. How many layers did that contain?

Machowina: It was a lot – around 150 textures. We did all the character animation in Toon Boom Harmony and then colored those in Photoshop. We invented brushes in Photoshop to replicate Anya’s style. We then created textures in After Effects for compositing. [For Pegasus] we delivered seven layers, with different colors, bumps, borders, outlines – everything that Quade needed.

The metaphor of the textures coming to life on the little porcelain creatures is presented poetically, without comment in the film. What did it mean to you?

Skrzypczyk: I think the film clarifies what a difficult position these people are [in] and how resilient they are – which, I think is beautiful. At Sundance, they had a gallery showcasing the figurines, and you needed a magnifying glass to look at the paintings. That’s how small and delicate they are. Somehow, they keep going. They keep making art, and that’s what the film is about. That’s what I think is beautiful about this connection of war and art. You can be small, but you can be powerful.