“Walt”: The Disney Biopic That Never Was

MIKE BONIFER co-produced the classic Disney Channel series Family Album, among many other projects during his long association with the Walt Disney Company. In 2008, he founded GameChangers, a company that designs storytelling and problem-solving systems for companies. He wrote the book GameChangers—Improvisation for Business in the Networked World, and is currently working on two new books, both about the applications of improvisation to human communication. For more information about his work, go HERE.

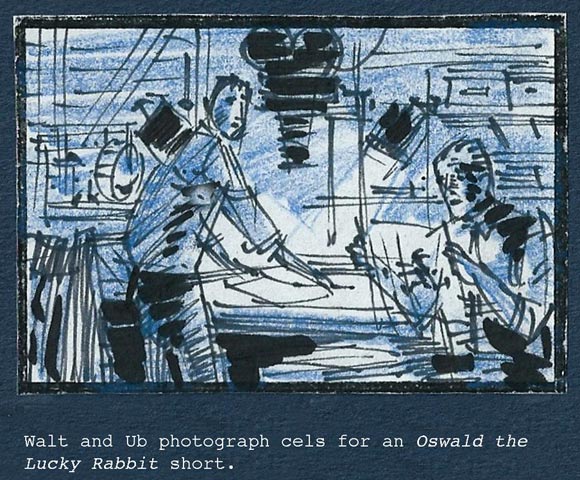

GALLERY OF SAM MCKIM ARTWORK FROM “WALT”

The drawings in this gallery and throughout the piece were drawn by Disney Imagineering legend Sam McKim for the Walt feature film pitch. The original format is 3” x 3” thumbnail drawings mounted on 5” x 7” boards.

IN THE EARLY 1980S, CARDON WALKER JR. AND I produced the Disney Family Album series for The Disney Channel through our company Mica Productions. It was one of the very first series funded by the Channel, and the first to get any kind of critical acclaim thanks to our nomination for a Cable Ace Award for Best Documentary Series. I think we lost to a CSPAN series about Walter Mondale getting a haircut. So we should have been humbled by the insignificance of our achievement. We were not.

We had a big ambition, and that was to land the Great White Whale of Disney myths, the life story of Walt himself. We had seen feeble feints made by the studio in this direction. Gauzy music videos made by variety show producers and Wonderful World montages of Walt’s TV intros produced by Imagineering. There’d been a good biography written by Bob Thomas. And that was about it. We knew we could do better, and were in a position to state our case. Cardon’s dad, Card Walker, had been a powerful and influential CEO at the company, had just retired, and still had lots of influence there. Having retired, his influence was probably not going to grow. Now was the time. How could any Disney Family Album series be legit, went our reasoning, without a portrait of its founding patriarch? Do Mormons not make stories about Joe Smith? Do African Americans not dream the myth of MLK onward? Why should Disney not do the same with its own hero’s story?

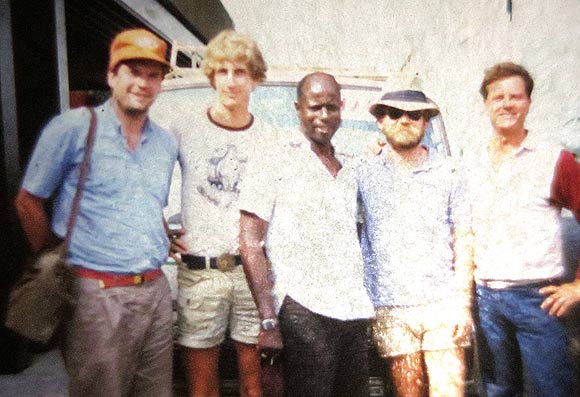

Mike Bonifer (far left) and Cardon Walker Jr. (second from left) in Africa during the production of “Baby, Secret of the Lost Legend.”

Cardon and I pitched Jim Jimirro, who ran The Disney Channel at the time, and his head of development, Peggy Christenson, on doing a telefilm about Walt. Jimirro and Christenson agreed to fund the development of a script. I’d like to think it was our stellar pitch, but the cold fact is that Jimirro owed Card Walker for giving him the job of running the Channel. What was he going to say to Card’s son and his producing partner?

Let’s put it this way: It didn’t hurt that our pitch was stellar.

The script, which I wrote with L. G. Weaver, took two years, from approximately 1984-86 to research and write. The final draft consisted of four parts, and was over 500 pages long. The four parts were: 1) Walt and Mickey, about Walt’s childhood through the birth and popularity of Mickey Mouse; 2) The Boy Who Would Be King; about the tumultuous great-and-awful events between Snow White and World War II; 3) A Castle at the End of Main Street, about the creation of Disneyland; and 4) Tomorrow, when Walt’s failing health and his utopian dream of EPCOT had him battling time on two fronts.

Cardon, Weaver and I spent six months doing research and conducting interviews with everyone we could find who had known Walt and worked with him. I rode the train back to Kansas City, and visited every address in Kansas City and Los Angeles where Walt had lived or worked.

Among my favorite interviews were the ones back in Marcelline, Missouri, with Walt’s childhood pal, Clem Flickinger, and Rush Johnson, who had been mayor of Marcelline when Walt came back to visit in the 1960s, and was quite a character in his own right. Johnson’s daughter and her family lived in Walt’s boyhood home, which Johnson had purchased. Clem still lived just up the street from the Disney homestead, in the same house he’d lived in when he and Walt were boys. One of the stories he told me about Walt is that when they were five years old, Walt got the idea to stage a circus in the basement of his house. The only act he had was his mother’s cat sitting on a stool. The only audience was Clem. Walt charged Clem a dime (“All the money I had,” said Clem) to get into the circus and watch the cat sit on the stool. When Walt’s mother found out that he’d charged his friend ten cents to get into a circus in her basement, she made Walt give Clem his dime back.

Another memorable interview was with Walt’s personal nurse, Hazel George. She lived in an apartment a couple of blocks from the studio. She was crippled, her body wracked by what I took to be MS or arthritis, and needing 24 hour nursing care. But Hazel’s mind was still lively, her memory clear and articulate. On two consecutive days, I sat next to the bed where she lay, her body as formless as a melted candle, and listened to her stories about Walt. She chose to tell me everything, including intimate details about the state of Walt’s marriage to Lilly, his failing health and the treatments they used for him, his relationship with other family members like his daughter, Diane, her husband, Ron Miller, and his nephew, Roy Edward Disney. What they gossiped about. Much of what she told me was too personal to be included in a studio-sanctioned project about Walt. All of it, however, informed how we depicted his character, particularly in the last couple of years of his life when he was getting almost daily physical therapy from Hazel in his office at the studio.

In doing the interviews it took to compose the script, I was always struck by how many different traits people who knew him ascribed to Walt—

- the faltering king who confided in his personal nurse;

- the young entertainment impresario who made money off his friend, Clem;

- the little brother who needed his big brother, Roy, to look out for him and bail him out when his dreams got unmanageable;

- the good uncle to Roy Edward who told his young nephew the story of Pinocchio when Roy was sick in bed;

- he was a “good systems guy” according to another former Disney CEO, Donn Tatum;

- “he wasn’t an artist but he had the soul of an artist,” according to Peter Ellenshaw;

- “he was curious and he’d try things, and he loved new-ness,” said Woolie Reitherman;

- he was the loyal friend who’d given Ub Iwerks a place back at the studio years after Ub had struck out on his own;

- Milt Kahl talked about Walt’s focus, and when Milt Kahl respects your focus, it’s serious focus;

- Jack Lindquist talked about the time a cantankerous Walt cussed out him and some other junior executives for not having a car ready for Walt at the Anaheim airport in a rainstorm; executives who’d started their Disney careers when Walt was around would talk about him as being “scary” because he’d talk to everybody in the company, and expected them to know more about their job than he did;

- he was the dad of the studio family who gave gifts of porcelain potties (pink for girls; blue for boys) to employees who had babies, and would spend time in the HR office after hours memorizing company IDs so he could greet people by name;

- there was the patriarch betrayed by his “boys,” the striking animators, a strike that would forever color his politics;

- he was the sentimentalist who cried at pencil tests of scenes that conveyed pathos;

- and of course, the dreamer, always the dreamer.

Not long after Michael Eisner took over as CEO of Disney in 1986, Cardon and I met with him, told him about the Walt project in development, and showed him the McKim sketches. He got excited about it. He told us he was planning to bring back The Wonderful World of Disney on Sunday nights, and Walt was a perfect intro to it. He told us it could run on four consecutive Sunday nights to introduce the series.

Naturally, Eisner was going to be enthusiastic. Cardon’s father had personally lined up the seven votes on Disney’s board that he controlled to support Eisner and ensure a unanimous board vote approving him for the CEO’s job. He had called George Lucas and (I think) Steven Spielberg on Eisner’s behalf, to get them to campaign with board members to ensure the vote.

We probably could have presented Eisner with a menu from Denny’s as a feature film proposal and he would’ve gushed. Still, Cardon and I felt that with Eisner’s support, we could overcome our inexperience in large-scale production and see our project through. Eisner, Frank Wells and Jeffrey Katzenberg were attracting a lot of talent to Disney at that time. Surely we would find champions and allies in the replenished studio talent pool.

Eisner asked to see the first draft of the script, and to keep him posted as we continued developing the project through The Disney Channel.

The next thing I remember happening is getting a call at my office from Christopher Vogler, who’d later go on to write The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. At the time Chris was doing script coverage for Eisner. He said it was an unauthorized call, but that he wanted to personally thank us for what he felt was one of the best scripts he’d ever read. “They have to do this,” he said.

One of the things you learn as a writer in Hollywood is that favorable script coverage does not pay the rent. As I had not yet learned this lesson, Vogler’s call sounded like the down payment on a home in Malibu.

Card Walker Sr. had warned Cardon and me that the Disney family would never approve a biographical treatment of Walt. This was also a concern echoed by Eisner. We took steps to get the Disney family’s approval. Our first step was to share the script with Walt’s oldest grandson, Chris Miller, who was an acquaintance, and like Cardon and me, had been producing stuff for the studio. Chris told me he finished reading the script while sitting in the airport in Baltimore and “cried like a baby.” He said he’d give the script to his mom, Diane, Walt’s daughter, to read.

I have always liked Diane. Getting to know her a little bit was as close I’ve ever come to Walt himself, both in terms of his physical appearance and his “don’t suffer fools” attitude. Diane was quick. I guess you have to be when you have like a dozen children. Walt had always wanted a big family. He was not able to produce one himself, so Diane got busy and took care of it. In an era of female executives, she would have made a great CEO. It didn’t take her very long to read the script. She called me at my office. She said the script seemed true to what she imagined her father’s life was like before she was born. She told me, though, that it stirred up some extremely uncomfortable memories, things that she would like to forget and would not like to see in a film about her dad. She was always, she said, sensitive to being singled out as “the girl whose dad is Walt Disney.” There are a number of scenes in Part 3 that deal with this dad-daughter conflict, and Diane and Walt’s testy relationship during the building of Disneyland. Both of them had hot tempers, and in the script things get bad between them before a beautiful scene has them reconciling the night of Walt and Lilly’s wedding anniversary party at the Golden Horseshoe Revue–a scene we depict in the script as the culmination of Opening Day at Disneyland.

“I’m not in favor of the studio doing this,” she told me, and my heart sank. “But I can tell how passionate you are about it,” she continued, “so I’m not going to stand in your way.” Now my heart did cartwheels. “This is a Disney family ‘Yes!’” I proclaimed to Cardon. A promise of no interference from the family should make Eisner and the studio happy!

How stupid I was about this. How wrong. How naive. This was the worst news we could possibly bring to Eisner.

Since our initial meeting, Eisner had gone ice cold on the project. See, The Wonderful World of Disney had already debuted with Eisner playing Walt’s role as host. And since our first meeting, Eisner had been featured on 60 Minutes, the cover of Time magazine and in countless other media as the poster boy for The Walt Disney Company’s turn-around. He was sitting courtside at Laker home games wearing chic new Mickey Mouse sweatshirts. Was putting his stamp on Disney’s architecture, too, with giant dwarfs for the Team Disney building in Burbank, and horizon-crushing Swans and Dolphins in Orlando.

After sending him our next draft, we met with Eisner again, and told him about Diane’s promise that she would not interfere. He didn’t miss a beat. “I saw Sharon (Walt’s other daughter) on the company plane last week when we flew to Florida for a board meeting,” he responded evenly. “She’s against it.”

Of course she was against it! It hit me like a cartoon safe. I saw stars and bluebirds circling my head. How could it help Eisner at this point to remind folks that there was this guy named Walt who had also been on the cover of Time magazine and had also hosted The Wonderful World of Disney? It couldn’t. Eisner was, as anyone would be, doomed to be diminished by any comparison to Walt. Eisner was Neo-Walt. And he was not about to let Original Walt mess it up.

Thus began the end game.

I don’t remember the exact sequence of these moves, but I do remember:

Roy E. Disney, Walt’s nephew, read the script and wanted to know why it wasn’t called Walt and Roy. Or better yet, Roy and Walt. Either way, he wanted more about his dad, Roy O. and less about Walt in the story. To me it sounded like a request for less magic, more magician’s assistant.

Jim Jimirro got replaced with an Eisnerite as head of The Disney Channel, so we no longer had a company home for the project.

We met with a studio exec Eisner sent us to, with a consolation promise of getting to produce a different telefilm. “Is it true Walt Disney had sex with the boys in the Mouseketeers?” was the only part of that conversation I remember. It was like being in a car crash. I have no recollection of what happened in the rest of that meeting.

During this same interval, I got a call from Ron Miller, Diane’s husband and the Disney CEO before Eisner, who told me that no matter what Diane had said to me in our earlier phone call, he spoke for her and the entire Walt side of the family in telling me they were against making the Walt Disney story. I believe he used the excuse that Walt’s widow, Lilly, who’d since re-married and outlived husband number two, was still alive, even though Chris Miller had told me that his grandmother would not know or care about the production of a Walt Disney story by the studio. My conversation with Ron reminded me of something else Chris had told me. “I once told my dad [Ron] that the studio ought to make a movie about my grandfather,” he said.

“What’d he say?” I asked.

“The same thing he said about every idea I ever gave him.”

“What’s that?”

“’We’ve already thought of it, and we’re not going to do it.’”

Discouragement began creeping into all our Walt-related dialogues.

I began to have subversive thoughts about telling an unauthorized version of the Walt story without the studio’s permission: “We’ll call it Thawing Walt,” I’d tell Cardon, and Thor Challgren and Art Swerdloff who worked with us at Mica. “An earthquake in L.A. cracks the cryogenics vault in Glendale where he’s frozen, and re-animates him when a live electric wire falls into his cryogenic fluid. Walt walks out of the vault like a zombie, with his skin falling off and everything. He’s a happy zombie. He talks like Mickey. But he’s misunderstood by the public. He terrifies children on school playgrounds….”

Cardon and I had only one more move we could make to sway Eisner. “Your dad delivered seven board votes when Eisner got the CEO gig,” I said to Cardon. “He’s got to tell Eisner this project is what he wants as payback for those seven votes.”

You’re Cardon Walker Junior, I’d say to my producing partner. Are Sid Sheinberg’s (President of Universal at the time) sons making cable TV series? No, they’re making movies. Is Frank Capra Junior making video press kits for cartoons? No, he’s making movies. You should be making movies, too!

Look at me, getting all killer like Barry Diller. Throwing elbows with your Time magazine cover-getters, breaking them and bending them to my will.

Now look at me being a Complete Idiot. Eisner had already paid off Card Walker for those board votes.

Cardon and I met in our office on Forest Lawn Drive (a fitting burial location) with his dad, former Disney CEO Card Walker, who was legendary at Disney for leading the team that bought up 28,000 acres of land outside Orlando without anyone finding out it was Disney doing it. Card told us he had no intention of pressuring Eisner to do the Walt project. “Winnie [his wife] and I have a lifetime deal,” he explained, “and I’m not going to mess that up.” Eisner and the Disney board, it turns out, had awarded Card Walker the lifetime title of Chairman Emeritus. Why would he entangle himself and his family in a financially orphaned, overly ambitious, politically charged project like ours? He would not.

And that was that. Checkmate. Redlight. Full stop. Period. Paragraph. End of story.

Except…great stories like Walt’s never really die. They are still out there, in a million different fractals, waiting to be reassembled and revealed anew, so that we may make better sense of the worlds we live in, and of our lives. Eventually, all great stories find their way.

Recently I came across the Sam McKim drawings in my attic. I was surprised when, five or six years ago, I gave a copy of the Walt script to Dave Smith for the Disney Studio Archives, and he didn’t want the McKim drawings. So I stored them and still have them. With Disney bringing the character of Walt back into the light in Saving Mr. Banks, I thought it would be an appropriate time to scan and share the drawings. Nobody’s getting anything out of them sitting in my attic. So here they are.

Most of what writers and producers experience in terms of turning scripts into original films is that it does not happen. There’s a lot of rejection, lots of blind alleys and dead end turnarounds. And so you learn, as I did with Walt, to reap the outcomes of the journey itself. The creation of the Walt script was an incredible experience just the way it was. It was my graduate degree in storytelling, my childhood, my political awakening all rolled into one. I’m thankful for everything about it, including the way it let me sniff out Michael Eisner’s Disney game early, which helped me continue working as a writer/producer/director with Disney as my primary client for the next 10 years, through the mid-1990s.

I hope The Walt Disney Company decides to tell the Walt Disney story someday, and if they do, I hope it’s about the Walt I got to know, and that they don’t Colonel Sanderize him—turn him into a simulacrum for a brand name, a hollow placeholder for the original human being. I hope they discover, as I did, a mortal man who believed he could fly, and convinced generations of people around the world that they could fly, too. A systems guy with the soul of an artist. A world figure who could still see the world through the eyes of child. The son of a socialist who fought unions at the studio he had built as a worker’s paradise. An impatient sentimentalist, whose tapping fingers would signal the animators that a scene wasn’t working and whose tears would tell them it was. A dying man with his greatest dream, of breathing life back into America’s inner cities, destined to go unrealized. A dad who rages at his daughter for wrecking the car in the studio parking lot while he’s giving her driving lessons, and later, on the night of his greatest triumph, insists that only she can drive him home.

From the script, the ending of Part 3:

A thoroughly exhausted Walt sits the backseat of the car with a program for the party at the Golden Horseshoe rolled up like a trumpet. As they exit the Disneyland property, Walt playfully toots his paper trumpet out the window several times, then curls up like a boy with a toy and, smiling a satisfied smile, closes his eyes.

Diane, driving carefully, glances at her father in the rear view mirror.

It’s a wonderful thing you’ve done for children, Daddy.

(without opening his eyes)

I didn’t do it for children.

A beat. Diane glances again at the mirror.

I did it for you and me.

Diane blinks back tears and fights to focus on her driving as we

FADE OUT