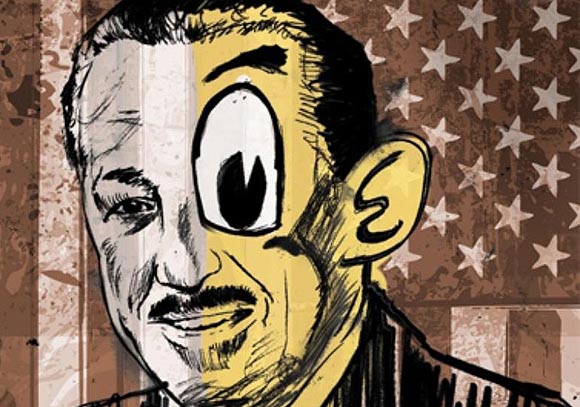

The Walt Disney Image Problem

Last weekend, The Guardian published a long-ish piece on Philip Glass’s soon-to-debut opera The Perfect American based on the novel of the same name by Peter Stephan Jungk. The book (and it appears the opera, too) is a veritable checklist of accusations that have been leveled against Walt Disney throughout the years: he was a McCarthyite, a racist, a misogynist, an anti-Semite, a megalomaniac. It manages to come up with new fictional flaws too, like philandering and incestuous obsession with his daughters.

Jungk’s book has been described by Walt Disney biographer Michael Barrier as “infantile” and “wretched.” That is perhaps why the Guardian reported that the Disney company called Glass to ask him not to work on the opera. The article also says that the finished opera was submitted to the Disney Studios for consideration, and there was no response. Jungk, the author of the book, said that he interpreted the company’s lack of response as “a green light.”

Glass says that despite all the negative (and untrue) traits the opera attaches to Walt, his intentions were noble:

“When I started out, people thought I was going to laugh at him. But I see Walt Disney as an icon of modernity, a man able to build bridges between highbrow culture and popular culture; just like Leonard Bernstein, who could jump from a Broadway musical to a Mahler cycle.”

To me, the opera is representative of a bigger problem faced by the Disney company, and that is that the company has been unable to present an alternative narrative to the perpetual vilification of Walt Disney in contemporary pop culture. The lack of honest and easy-to-access information about Walt is precisely why a majority of teens and twenty-somethings today have a wildly distorted and inaccurate view of Walt Disney, the man.

The Disney company could do much more to humanize the founder of their company. Instead the company has taken the tactical approach that its founder must be deified. In response, they build statues of Walt using every conceivable material that is known to mankind, from bronze to Tom Hanks.

These statues end up being as one-dimensional and untrue as the negative portrayals. Today’s generation is too savvy to accept an image of Walt Disney as an irreproachable god-like entity, and so they seek their truth elsewhere. It is through this cycle that the Disney company continues to lose control over its founder’s image.

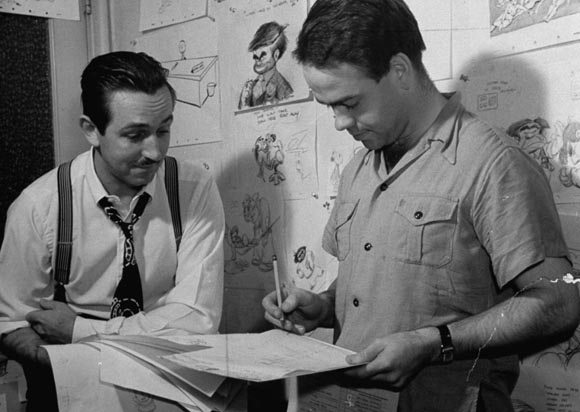

Disney animator and director Ward Kimball, the subject of my own as-yet-unpublished biography, rebelled in his own idiosyncratic fashion against the Disney company’s deification of Walt, which he felt diminished the man’s accomplishments and tainted his legacy. Ward never censored himself when he was asked to speak about Walt Disney at public functions. He made sure to incorporate stories about honest human interactions with Walt, of which he had more of than almost any other artist who worked at the company. In Ward’s stories, Walt may have used a cuss word and he may have just walked out of the bathroom after taking a shit, but he was a human being who people could recognize, understand, and most importantly, admire.

The Disney family-operated Walt Disney Family Museum, in its own way, does a great job of humanizing the founder of the company. However, the museum is not a panacea for Walt’s image problem because its impact is limited to tourists and Disney fans. It cannot combat the steady stream of misinformation about Walt from mainstream cultural sources like Family Guy and Saturday Night Live.

The Disney company itself, with its vast media reach, is in the best position to rehabilitate the image of its founder and offer a counterimage to the flood of negative portrayals of its founder. A good first step would be to acknowledge the fact that Walt Disney wasn’t a god, but a human being.