RIP: Edward Levitt, 96, Disney Background Painter and Cartoon Modern Designer

Edward Levitt, an unsung hero of the Golden Age of animation, has died. He was 96. Levitt died on Tuesday, April 2, in Palmdale, California.

Levitt worked as a director, production designer, storyboard and layout artist, and background painter for thirty-five years in the animation industry. His superb skills as a designer made him a key figure during the Cartoon Modern era of the 1950s.

Ed Levitt was born in New York City on April 17, 1916 and grew up in Somers, Connecticut and Brooklyn, New York. His family moved to Los Angeles in the mid-1930s and following graduation from high school, Levitt applied to the Disney Studios in 1937. He was hired at $16.50 per week and did rotoscope tracing on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

The Disney studio recognized his talent as a painter, and by the end of production on Snow White, he had switched to painting backgrounds. He worked as a background artist on Pinocchio, the “Rite of Spring” segment in Fantasia and Bambi.

Here are a couple examples of his paintings from Fantasia and Bambi:

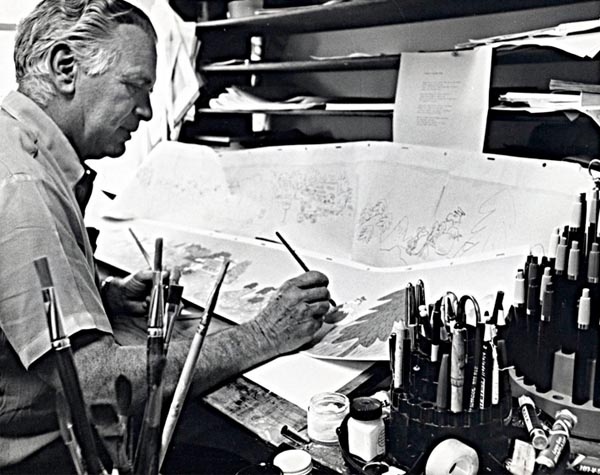

Levitt picketed during the Disney strike of 1941. He returned after the strike was settled to work on Victory Through Air Power, but left again to enlist in the Marines in 1943. During the war, he made training films while a member of the Marine Corps Photographic Section in Quantico, Virginia. The following photo shows Levitt during the time he was stationed at Quantico:

After the war, Levitt became a partner in a Los Angeles-based production company called Cinemette, which was formed with ex-Marines (and Disney artists) John Chadwick, Jack Whitaker, and Keith Robinson. The studio operated between 1946-1950, and they created a number of industrial films, as well as entertainment short subjects and early TV commercials.

Levitt’s liberal politics led him to direct Grass Roots (1948), which called for establishing a world government through a revision of the United Nations charter and was partly funded by the United World Federalists. He also produced a popular anti-nuclear animation film Where Will You Hide? (1948), which attracted the attention of no less than Albert Einstein, who commented, “Somebody, after having seen this film, may say to you: This representation of our situation may be right, but the idea of world government is not realistic. You may answer him: If the idea of world government is not realistic, there there is only one realistic view of our future: wholesale destruction of man by man.”

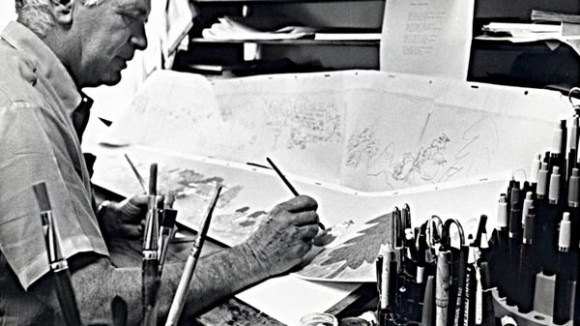

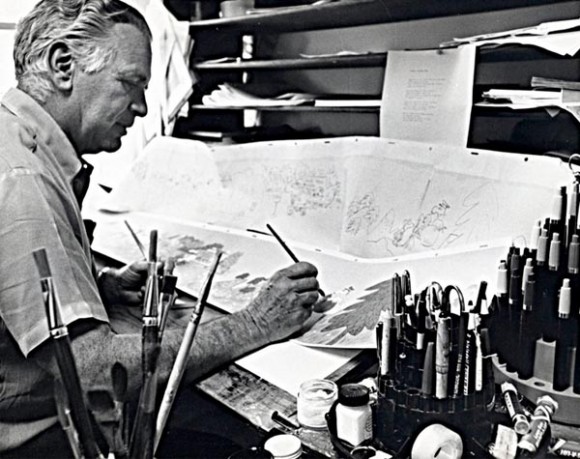

Levitt’s star rose during the 1950s when commercials and commissioned films were produced at an increasingly frenetic pace. His spare but visually sophisticated style was ideal for advertising, and he was much sought after as a designer, storyboard and layout artist. “He was a great artist,” said animator Bill Littlejohn. “And his layouts were the best. He could animate, too. I sure liked working with him. He was so damn good at what he did. He knew the problems that the animators would face and he would design things with that in mind.”

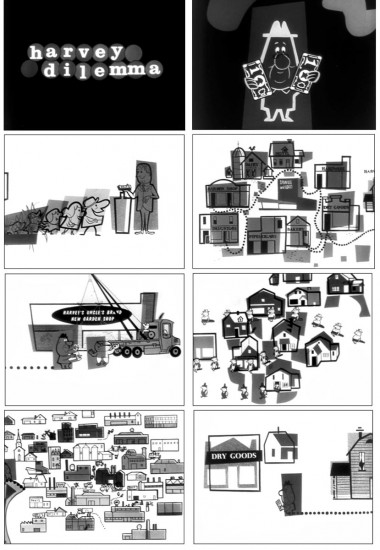

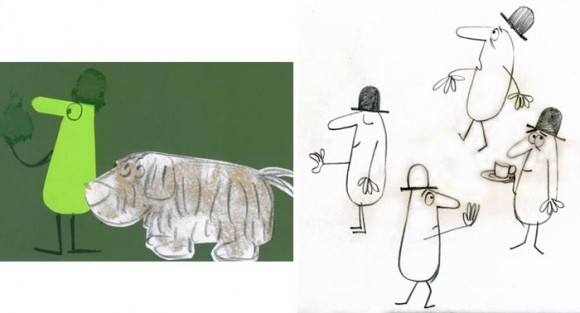

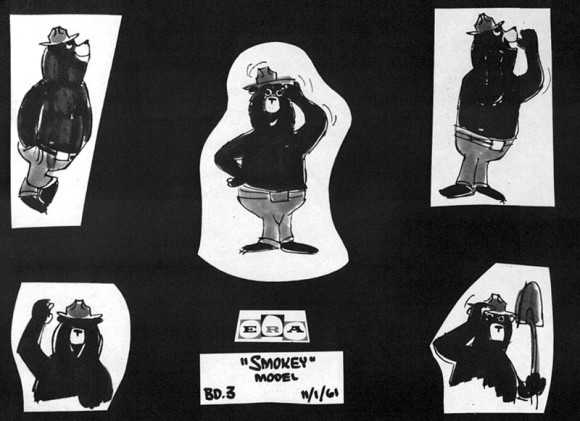

These are a few examples of commercials and films designed and laid out by Levitt:

Through the 1950s, Levitt worked as a freelancer at nearly every major commercial studio in Los Angeles including Graphic Films, Cascade Pictures, Raphael G. Wolff, Quartet Films, John Sutherland Productions, Eames Office, ERA Productions, United Productions of America, Ray Patin Productions, Academy Pictures, Churchill/Wexler Film Productions, Storyboard Inc., and Fred A. Niles Productions.

At Playhouse Pictures, Levitt worked closely with director Bill Melendez on many of the Ford spots starring the cast from the Peanuts comics. When Melendez opened his own studio in 1964, Levitt was one of the first artists he hired.

“I remember Ed as being reliable, steady, pragmatic, kind and generous,” said Melendez’s son Steve, who also worked at the studio. “I know that he helped Bill in the early days not only artistically but also financially. Bill always considered Ed to be ‘The Best’, a title he did not bestow easily or often. Ed could draw anything and had a great grasp of how a film is made. He was the best layout person I have ever met.”

Levitt played a key role in designing the first Peanuts special, A Charlie Brown Christmas. This was one of his backgrounds from the film:

He also coined the famous credit used for many years at the end of the Peanuts specials—Graphic Blandishment. “Blandishment” is defined as “something that tends to coax or cajole,” which speaks to Levitt’s modesty and his view of the role he played in the filmmaking process.

Steve Melendez recalled that Levitt was proud of A Charlie Brown Christmas even during times of uncertainty and doubt:

“When we completed A Charlie Brown Christmas, and we all had a chance to look at the answer-print, Bill, Lee [Mendelson] and everyone else thought we were the authors of a great disaster and we would probably never make a film again. Ed was the sole voice who said, ‘Don’t be silly, this film will be shown for a hundred years!’ And he was right. I don’t know if he believed it or not, but his calm confidence gave everyone hope that perhaps things were not as bad as they seemed.”

By the early-1960s, Ed identified himself as a Cartoonist-Rancher on his income tax returns. He had purchased a ranch in Lake Hughes, an hour’s drive north of Los Angeles, near Gorman, California, and had began taking animal husbandry classes at Pierce College. At his orchard, he planted cherry and apple orchards, and began to raise cattle.

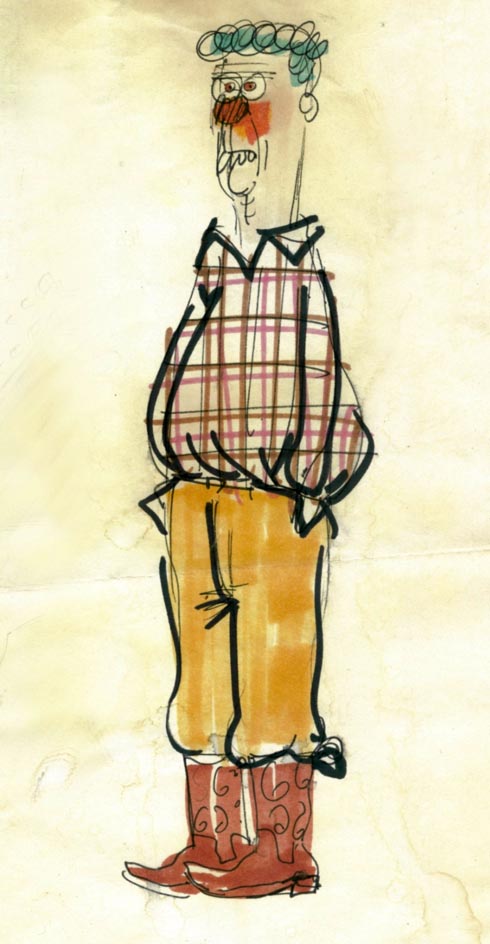

Bill Melendez made this drawing of “cartoonist-rancher Ed”:

He spent most of the 1960s working on the Charlie Brown TV specials, and also directed a couple of Babar specials for Melendez. Other Sixties projects included the titles of It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World, and the features Gay Purr-ee and The Incredible Mr. Limpet.

Levitt retired from animation in 1973 to become a full-time rancher and orchard owner. “As you get older,” Levitt told a newspaper reporter, “it just seems a lot nicer to sit up here in the forest and listen to the trees grow.”

This is a photo of Levitt (left) operating his “pick-your-own” orchard in later years:

Levitt is predeceased by his wife, Dorothy. He is survived by his brother, Julius Levitt; sister, Annette Priemer; his four children, Alan Cyders; Geoffrey, Dan and Paul Levitt, along with numerous grandchildren and great-grandchildren. In lieu of flowers, the family has requested that donations be made in his name to the Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital.