Lady and the Lawsuit: Peggy Lee’s War With Disney

As the United States heads into its Labor Day weekend holiday — and with an eye to Lady and the Tramp’s 60th anniversary celebrated earlier this year — now would be a good time to remember the lesson of pop star Peggy Lee.

Not too long after its 1955 bow, Lady and the Tramp became Disney’s biggest box office hit since 1937’s phenomenal Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Film historian Neal Gabler’s biography, Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination, noted that Lady and the Tramp reestablished the warm, rounded Disney animation style, which served as a rebuke to the modernist, limited animation style that had won acclaim for UPA, its premiere stylistic proponent.

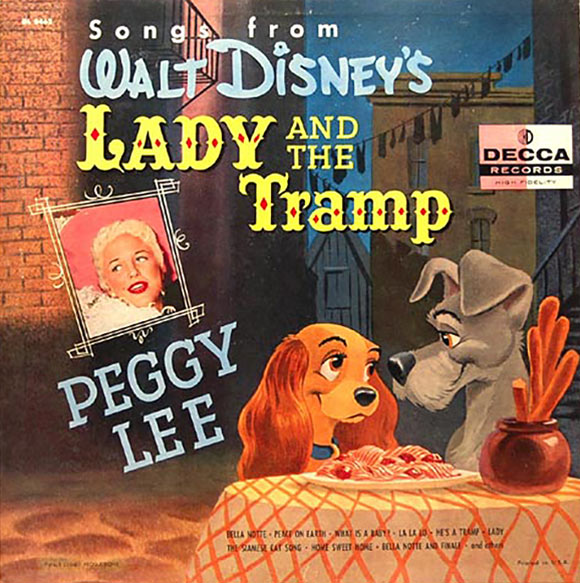

Perhaps most memorably, Lady and the Tramp’s soundtrack featured songs now considered to be key contributions to the Disney songbook, including “He’s a Tramp,” “The Siamese Cat Song,” and “Bella Notte.”

But the film’s most significant contribution to history may possibly be found elsewhere: entertainment contract law.

Is That All There Is?

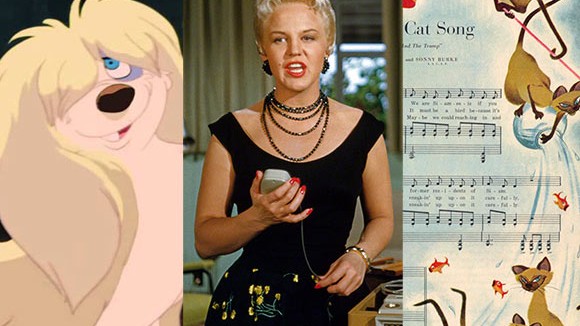

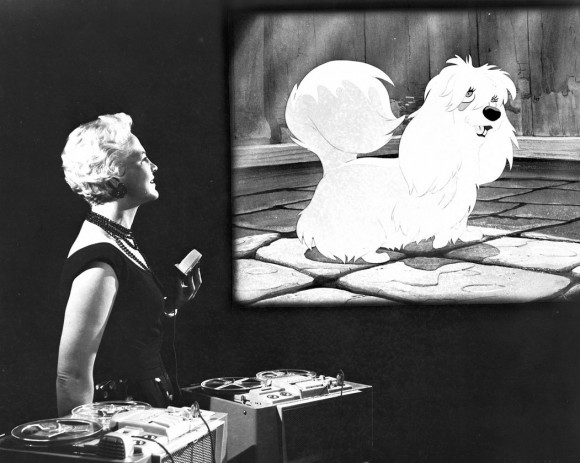

Few contributed as much to the success of Lady and the Tramp as the singer and actress, Peggy Lee, who performed the role of the sultry Pekingese Peg, as well as the twin Siamese cats Si and Am. In his recent biography, Is That All There Is: The Strange Life of Peggy Lee, James Gavin details not only her many contributions to the animated classic’s music and voice tracks, but also to its storyline.

Gavin describes how Lady and the Tramp’s script originally called for Old Trusty the bloodhound to be run over by a dogcatcher wagon and killed, to create dramatic tension. With memories of her own dog dying in her arms years before, Lee worried about the effect the Old Trusty’s death might have on children in the audience, and convinced Walt to let the beloved bloodhound live. And so instead at the film’s denouement, Old Trusty hobbles around on a bandaged leg, with Lady and her Tramp’s little puppies scrambling around before him.

But Lee also directly influenced the story’s characters, particularly the dog pound vamp, Peg, who was originally named Mame. When Walt Disney asked for Lee’s permission to name Peg after her, she quickly agreed. Animator Eric Larson even studied Lee’s movements as she strutted around his office, to get Peg’s attitude just right.

According to Gavin, Lee made all of these contributions for a grand total of $4,500 in fees: $3,500 for the voices, and $1,000 for the songs she wrote — which was split with her co-songwriter, Sonny Burke. Gavin noted that this was a respectable sum in 1955, as no one at the time foresaw the fortunes to be had in home entertainment. Because Lee had an exclusive recording contract with Decca Records, her contract with Disney specified that Disney “retained no right to ‘make phonograph records and/or transcriptions for sale to the public.'” As used in the recording industry, “transcriptions” commonly referred to audio discs produced for radio broadcast, not for commercial sale.

That usage in Lee’s contract would prove unfortunate.

You Say Transcriptions, We Say Copies

In 1987, Disney released Lady and the Tramp on VHS, selling 3.5 million units in one year. The film soon became the best-selling home video of all time.

Disney reported $90 million in profit from Lady and the Tramp’s VHS release and, reluctant to share its windfall, offered Lee only a nominal fee for promotion of its release. Insulted, Lee hired New York copyright litigator David Blasband and his partner, Alvin Deutsch, who brought Disney CEO Michael Eisner’s attention to the contractual language about rights to “transcriptions.” In their view, “transcriptions” was synonymous with “copies,” meaning that Disney had already contractually agreed they had no right to sell copies of Lee’s works to the public. By selling VHS copies of Lady and the Tramp to the public, Lee’s lawyers contended, Disney had violated that provision of the agreement.

Envisioning every artist they had contracted now demanding shares of their vast video bounty, Disney rejected Lee’s argument. Disney already employed a large legal staff, the finest lawyers money could buy. Gavin quotes Eisner as explaining that, “When it comes to intellectual property, you can’t be too litigious.”

Indeed, the law arguably demands it: The doctrine of acquiescence requires that a party with rights defend those rights. Otherwise, that party is deemed to have acquiesced to an infringement of those rights. Disney often argued it had no choice but to be litigious.

But it was that litigiousness that tripped up Disney in its battle against Peggy Lee.

Gavin recounts Lee’s lawyer David Blasband researching a lawsuit Disney had pursued against Alaska Television Network in 1968, for airing copies of its films without consent. In the suit, Disney relied on a definition of “transcription” from the 1909 Copyright Act, which defined it as a “copy.” Blasband confronted Disney with this earlier case in court: “transcriptions” meant not just audio discs but also “copies,” which Disney recognized on record.

The argument persuaded Judge William Huss of the Los Angeles County Superior Court to rule for Lee, finding that Disney has breached its contract. Only the value of damages remained to be determined.

The Performance Of a (Legal) Lifetime

For two weeks, lawyers argued about the value of Lee’s contribution.

Lee herself showed up to testify. Frail and bound to a wheelchair, she was still able to give “a performance as shrewd and winning as any from her musical heyday,” Gavin wrote in his biography. Cheech Marin, who had been recruited by Jeffrey Katzenberg to testify on Disney’s behalf, observed that the only way Lee’s legal team could have made her look more compassionate was “if they’d brought her in on a stretcher.”

Another Disney witness, Jodi Benson, the voice of The Little Mermaid’s Ariel, was supposed to testify that actors worked with the company for prestige (not money) and that the voice actor’s role was minor within the overall context of the film. But Benson was so starstruck by Lee’s presence that her testimony ended up hurting Disney’s defense. “I remember her testifying to the effect that whatever the jury wanted to give [Lee], she deserved that and more,” recounted Lee’s lawyer Blasband. “She greatly weakened Disney’s position. She was probably the best witness we had except for Peggy herself.”

In the end, the jury awarded Lee $2.3 million.

Lee was vindicated. She proved Disney, and its army of lawyers, could be beaten. “I’m not being a saint, saying I don’t want the money — I want it,’ Lee told the NY Times. “I think it’s shameful that artists can’t share financially from the success of their work. That’s the only way we can make our living.”

For its part, Disney also learned something quite well. Now, its standard contractual language requires that artists surrender rights to their work for exploitation in “all media, now known or hereafter devised.”