The Largest On-Line Stash of Robert Osborn’s “Dilbert”

I’m not much for compiling lists of favorites, but if I had to ever list my favorite cartoonists, there’s no question that Robert Osborn would appear high atop the pantheon of greats alongside other cartooning heroes like Ronald Searle, Otto Dix, Vip Partch, Rowland Emett, and Miguel Covarrubias.

Osborn’s work has been on my mind recently. His name came up in a conversation a few days ago, and then there was Jerry’s post about Grampaw Pettibone, a character that Osborn designed and drew for a long time.

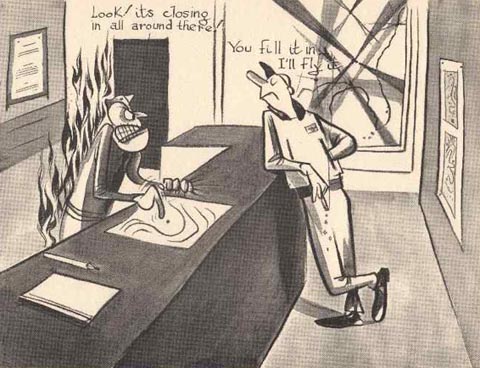

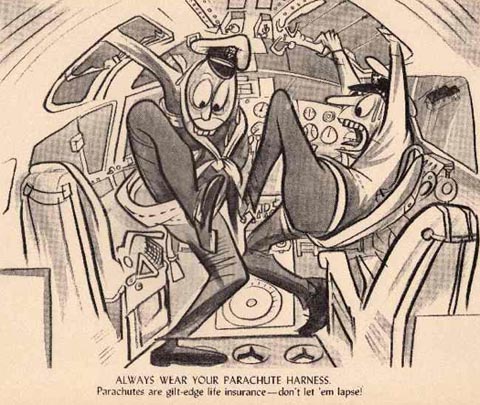

Osborn is the definition of late bloomer. He was approaching forty years old when he began drawing cartoons for the Navy, his first major body of work. He created between 2,000-3,000 drawings for posters and military training booklets, many of them featuring Dilbert, a goofball pilot who did everything incorrectly. It’s a crime that these drawings have not been collected nor reprinted anywhere since their original publication seventy years ago.

Thankfully, there’s the Ask a Flight Instructor website, an unlikely repository of Osborn’s work, collecting nearly 600 of his drawings from that era. It’s easily the largest collection of Osborn’s wartime work that I’ve ever seen and it’s a real treasure. The drawings are all related to the operation of aircraft and aimed squarely at pilots, but from a cartooning standpoint, they can be appreciated by all.

The first thing that strikes me about these drawings is the quality of Osborn’s line. The texture, the dynamism, the intensity–diminished somewhat by the low-res scans on-line, but still plainly evident. In my opinion, he had the most exciting line of any cartoonist.

Years ago, I had a conversation with cartoonist Eddie Fitzgerald and he theorized (quite eloquently, I might add) that the content of Osborn’s work was overshadowed by the sublime beauty of his line. I wouldn’t go quite that far, but the point is well taken–Osborn’s line is that of a master draftsman’s; we’d be more accustomed to seeing such elegant work hanging in an art museum than reprinted in instructional booklets for aviators. Osborn, said art historian Russell Lynes, “has never been one to observe too closely the distinction between cartooning and pure painting.”

The real thrill, however, is seeing how Osborn applies that line to the art of cartooning. He doesn’t hesitate to twist and distort forms, caricature expressions, anthropomorphize airplanes, and gag up an idea. And he does it all using a naturally funny and inventive drawing style which evolved to even greater heights in the years following his Navy cartoons.