How to Look At Ad Reinhardt, The Cartoonist Who Was A Fine Artist

Ad Reinhardt (1913-1967) was an artist’s artist, renowned among critics and curators, but hard for the general public to warm up to. His most famous fine art works are his “black” paintings, from the 1960s, which at first glance appear to be solid black, but on closer inspection turn out to be blocks of black and almost-black shades. Important, but challenging.

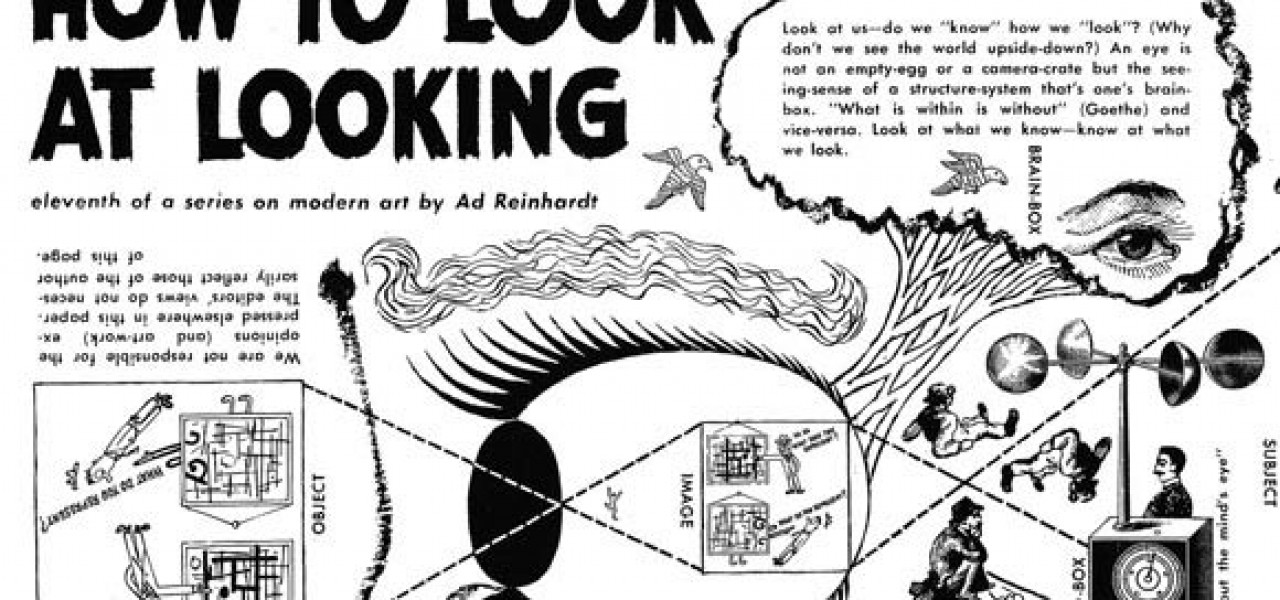

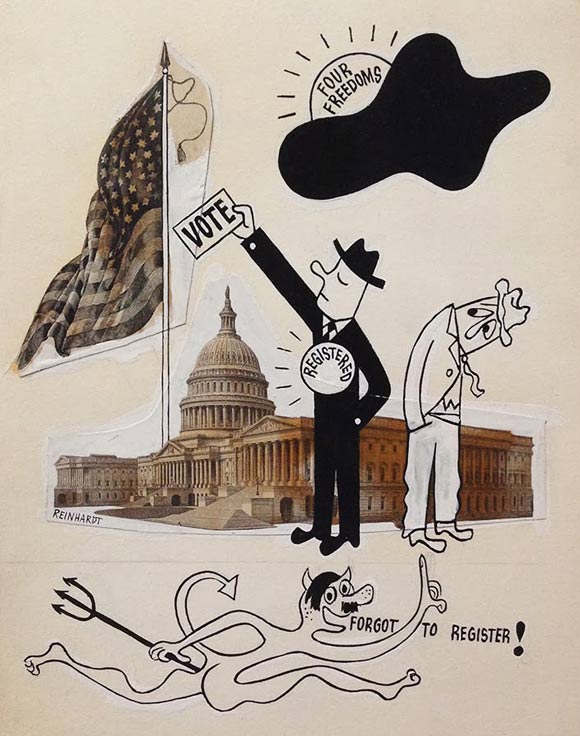

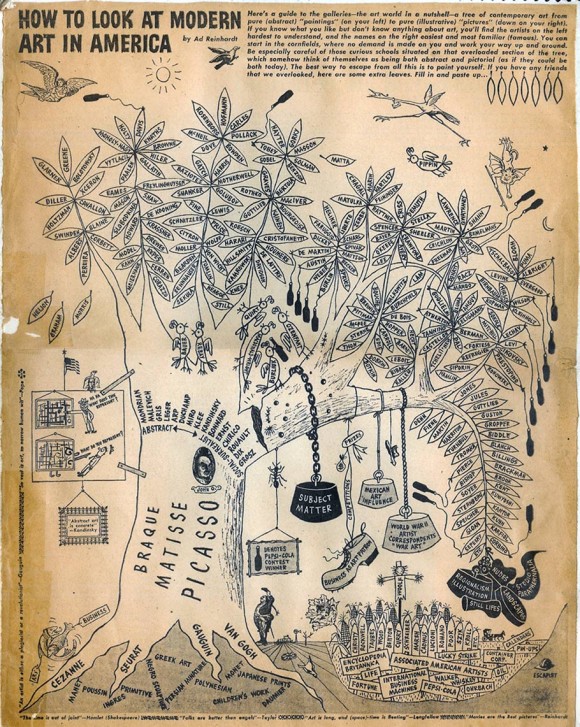

Reinhardt’s other artistic oeuvre is more easily accessible though: during the late-1930s and ’40s he drew comics and illustrations, mostly for the liberal newspaper PM, but also for New Masses, The Saturday Evening Post, and Ice Cream World, among others. His educational/editorial series, “How to Look at Art,” which championed abstract art and the ideas that would lead to Conceptual art and onward, have often been reprinted in art history textbooks. An exhibition last December at the David Zwirner Gallery in New York paired Reinhardt’s fine and comic artworks, a rare occasion when both types of work were featured on an equal footing.

In his comics, Reinhardt kept up with the changing face of cartooning, producing works that eschewed traditional perspective and realism to something much more “cartoon modern”—a style that was at the same time growing in many places, from the cartoons of Saul Steinberg to the newly formed United Productions of America animation studio. Like his fine art, Reinhardt’s comic drawings capture a number of different styles. His occasional use of repurposed older images looked back to Max Ernst’s Une semaine de bonté (1934), a graphic novel made of of recycled, collaged Victorian-era illustrations, and forward to the animations of Terry Gilliam or David Malki!’s Wondermark comic strip. One of Reinhardt’s most famous cartoons, “What does this represent…” manages to straddle different periods of cartoon history, presenting a modernistic blank background and childlike human figure, such as would become more common in following decades, with an old-fashioned painting coming to life.

Many people knew Reinhardt’s drawings through the illustrations he did for anthropologists Ruth Benedict and Gene Weltfish’s 1943 pamphlet, The Races of Mankind. Despite being banned from sale at Army bases and U.S.O. clubs by the government—its earnest, even liberal, discussion of the commonality of all races (and Reinhardt’s drawings) having troubled some in Congress—it sold very well, was adapted for use in schools, and provided inspiration for UPA’s seminal work, The Brotherhood of Man (1946).

A companion book to the recent Zwirner exhibit, Ad Reinhardt: How to Look: Art Comics, with text by Robert Storr, dean of the Yale School of Art and curator of the exhibition, was published last month. The Brooklyn Rail also published a 172-page tribute issue to Reinhardt, which is available for $10 in their online store.

Below is an informative video of Storr leading a walk-through of the Reinhardt exhibit:

All Ad Reinhardt images © 2013 Estate of Ad Reinhardt/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

.png)