Mexico Is Creating A Digital Database To Protect Its Animation Heritage

Mexican animation featured heavily at this year’s Annecy Festival, with the French event picking the country as its 2023 territory of honor.

One of the standout features of this year’s festival was Annecy’s Mexican Archaeology sidebar. Working in collaboration with Mexico’s Filmoteca UNAM, Annecy hosted a historical retrospective of Mexican animated films produced between 1935 and 1982. During this period, though production was non-constant, it was wildly diverse and regularly featured work that addressed timely political and cultural topics.

The program was created to feature experimental and historical works that reflect the incredible range present in Mexico’s animation production history, including notable milestones such as the first documented short film made by a woman and the first computer-created animation.

Last year, after it was announced that Mexico would be the 2023 Annecy guest country, an initiative was launched to create a digital archive of historical Mexican animation pieces that could be screened at the French festival. And, although this year’s Annecy program has now wrapped, those responsible for curating the program have more ambitious plans to continue their digitization efforts while also restoring many films that have been neglected over the decades.

The Mexican Archaeology program was curated by visual artist Tania de León and the head of the ongoing archival initiative is Ana Cruz. We spoke with both women during Annecy to find out about this year’s specially curated sidebars, the larger initiatives being executed to preserve Mexico’s animation history, and when these films will be more broadly available to audiences in Mexico and abroad.

Cartoon Brew: What inspired this mission to digitize these classic animated works?

Ana Cruz: A large part of the inspiration or excuse to start the work on the collection was the curatorship of the programs that would be presented in Annecy. Doing this work, the team realized that it was necessary to digitize some of the important short films from our history and the importance of creating an animation collection for other programmers, researchers, and professionals in the industry.

Cartoon Brew: How did you decide which films to include in the selection? What were the criteria?

Tania de León: The main thing I considered when choosing the movies was diversity. I didn’t want to focus on just one type of animation, so I made sure to select a variety of films, both regarding the topic and the techniques. The first step was to see what materials were available, and based on that, we ended up with a selection that includes some really interesting choices.

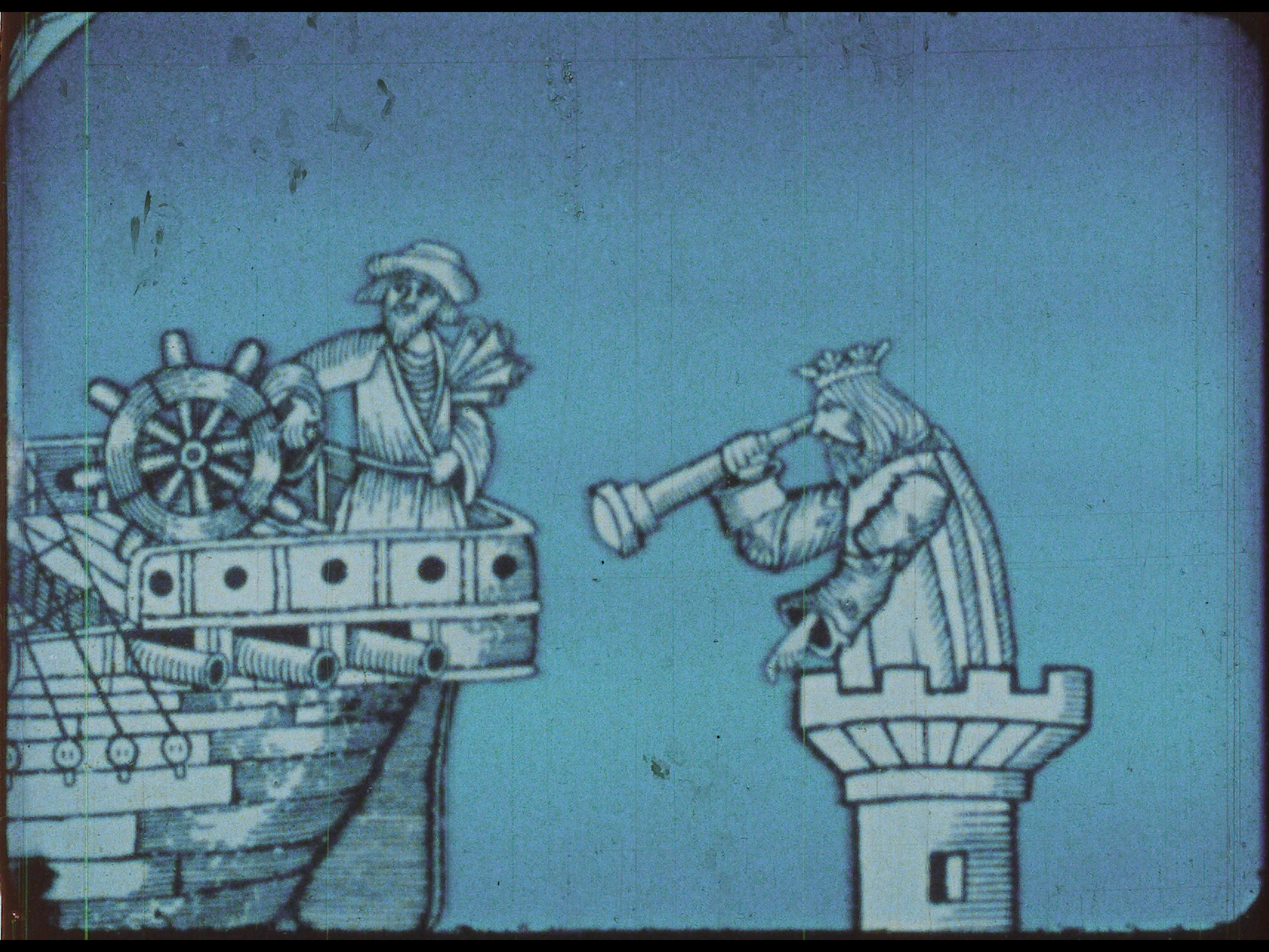

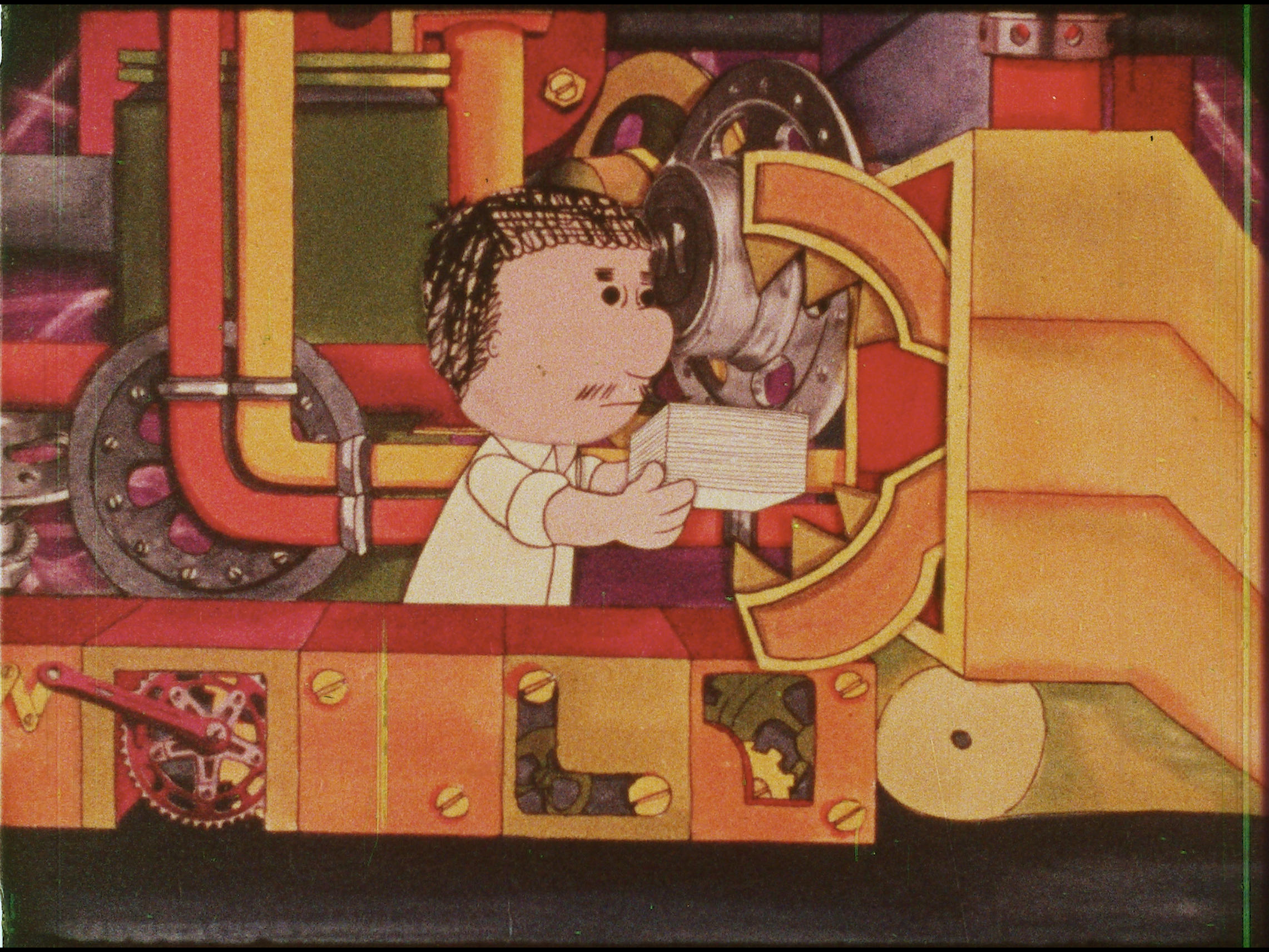

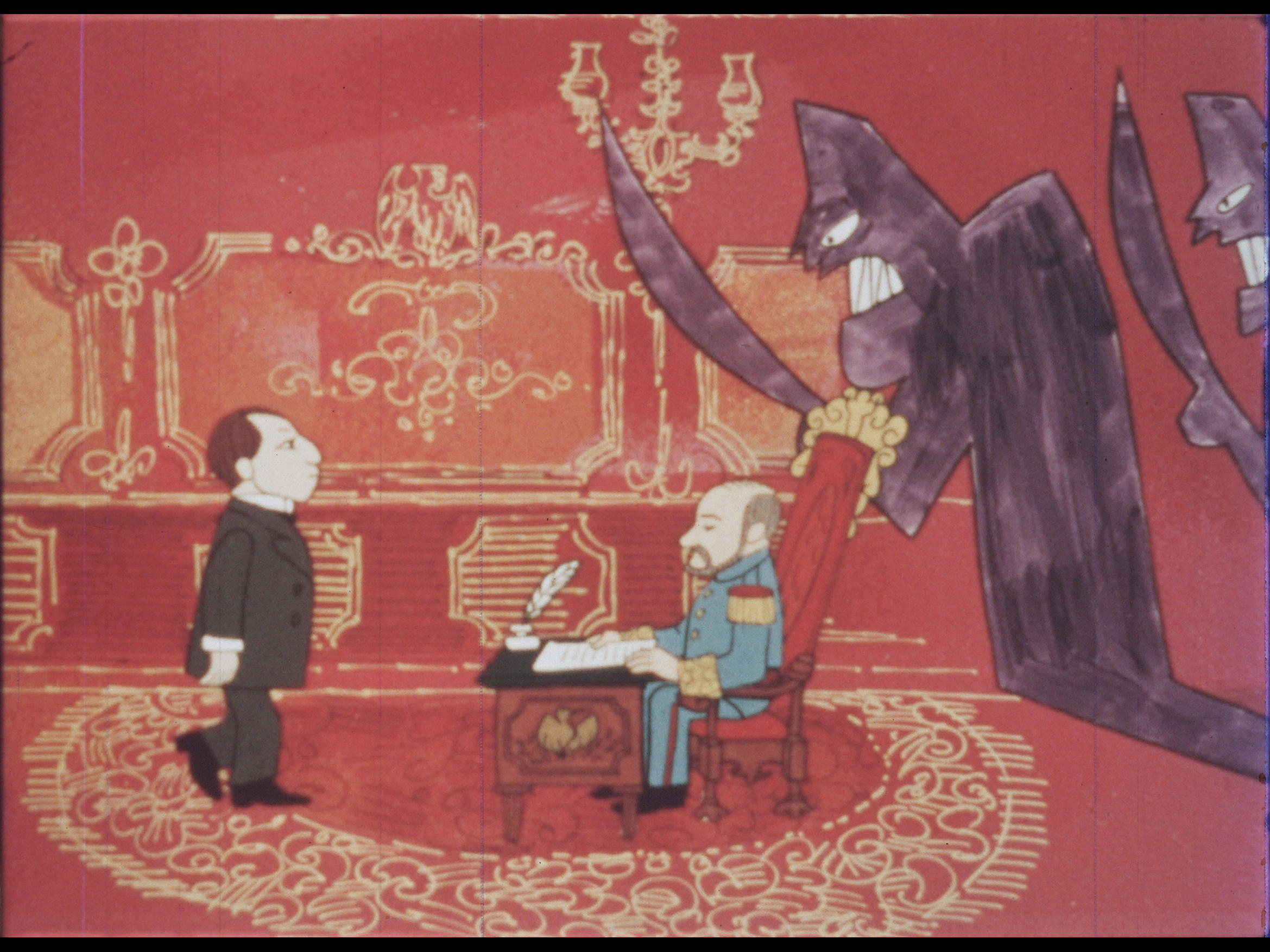

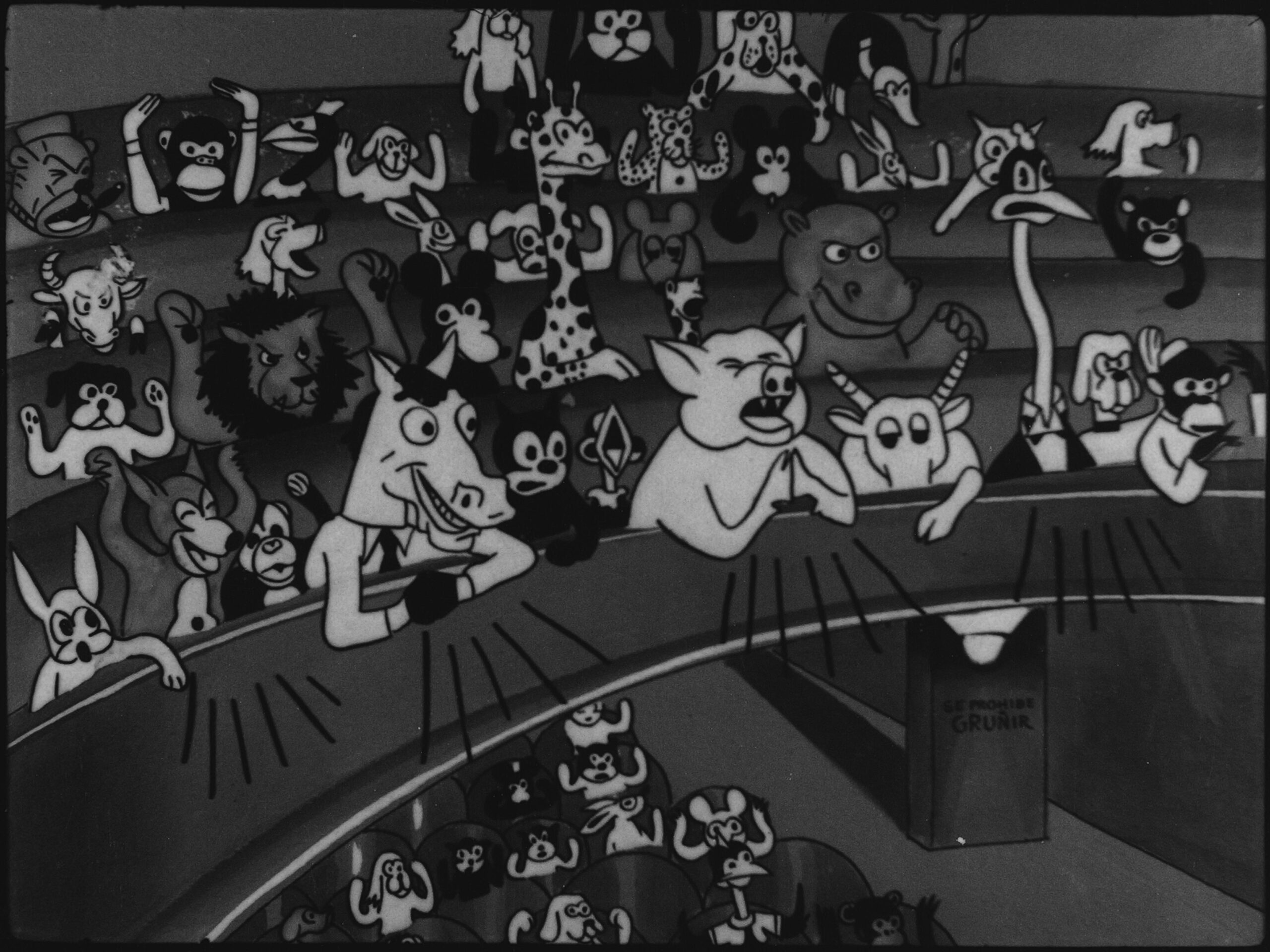

One of the films we included is Paco Perico in Premiere (1935), which is one of the earliest examples of entertainment films. Then we have Crónicas del Caribe (1982) and La Persecusión de Pancho Villa (1978), both of which have political content. El Compa Clodomiro y el Capitalismo (1981) also falls into this category. Juarez (1972) depicts the life of Benito Juarez, in a version for young audiences. Another unique film we selected is Punto, Línea y Simetría (1976), which is an abstract computer-generated film that hasn’t been shown since the 1970s. And finally, we have Y si eres mujer (1976), which is the first animated film made by a Mexican woman. So, these were the criteria I used to decide on the movies for the selection: diversity in terms of animation styles and genres, availability of materials, and the historical significance of the films.

Can you tell me more about the digitalization process that’s happening now? And are there any efforts being made to restore any of the films?

De León: Filmoteca UNAM, which is responsible for preserving and restoring historic Mexican films, played a key role in digitally preserving these movies, specifically for the Annecy Festival. While the focus, for now, is on digitalizing the films, the curator team I am part of is aware of the importance of restoration for animated Mexican films. In the near future, we will be exploring possibilities for restoring these animated films, ensuring their preservation and bringing them back close to their original version. So, the digitalization process carried out by Filmoteca UNAM was crucial for the preservation and accessibility of these films, and our curator team is committed to furthering the restoration efforts for animated Mexican films in the future.

How long have you been working on the database and how much longer do you think it will take to finish?

Cruz: The curatorial team has worked from September 2022 until now with this historical compilation work. Over the next six months, we will continue working on creating a database together with the UNAM Film Library and diagnosing the short films that are in 16mm and 35mm that most urgently require digitization and restoration. Over the coming year, we will seek to carry out this recovery work.

Can you see influences from these films in the animation being produced in Mexico today?

De León: While it may be challenging to directly pinpoint influences from these specific films, considering their relative obscurity, it’s important to note that political themes have always been present throughout the history of animation in Mexico. Although contemporary animators may not be consciously drawing inspiration from these particular movies, the broader tradition of addressing political and cultural topics in Mexican animation can be observed. An excellent example of this was presented in The Untold Stories (Mexican animation tribute), which also screened at Annecy. This program showcased the enduring presence of political themes in Mexican animation and served as a testament to the ongoing exploration of these subjects by contemporary animators.

Aspects of Mexican culture can also be observed in the programs we presented. While direct influences may not be easily discernible, the rich cultural heritage of Mexico undoubtedly permeates the work of today’s animators, contributing to the unique artistic expressions found in Mexican animation.

Will there be any way for people in Mexico to access these restored films in the future?

Cruz: The plans for after Annecy are to find spaces to exhibit the cycles created in national and international festivals and in embassies. One of the first is the Pixelatl Festival to be held in September. Similarly, the completion of the database will continue to make the content and information accessible.

Each of these films is a treasure, but are there any that you think hold particular historical significance?

De León: While all the films in the selection hold significance, I would like to highlight two titles that are particularly important for their unique contributions. The first is Y si eres mujer (1976, pictured at top) by Guadalupe Sánchez Sosa. This film is of special importance because it represents the work of women in animation, which has often gone unrecognized and underrepresented. It is crucial to shed light on the history of animation in Mexico and give visibility to the contributions made by women. Y si eres mujer serves as a reminder that women have been involved in both the industry and independent filmmaking, and their names and works deserve recognition and appreciation.

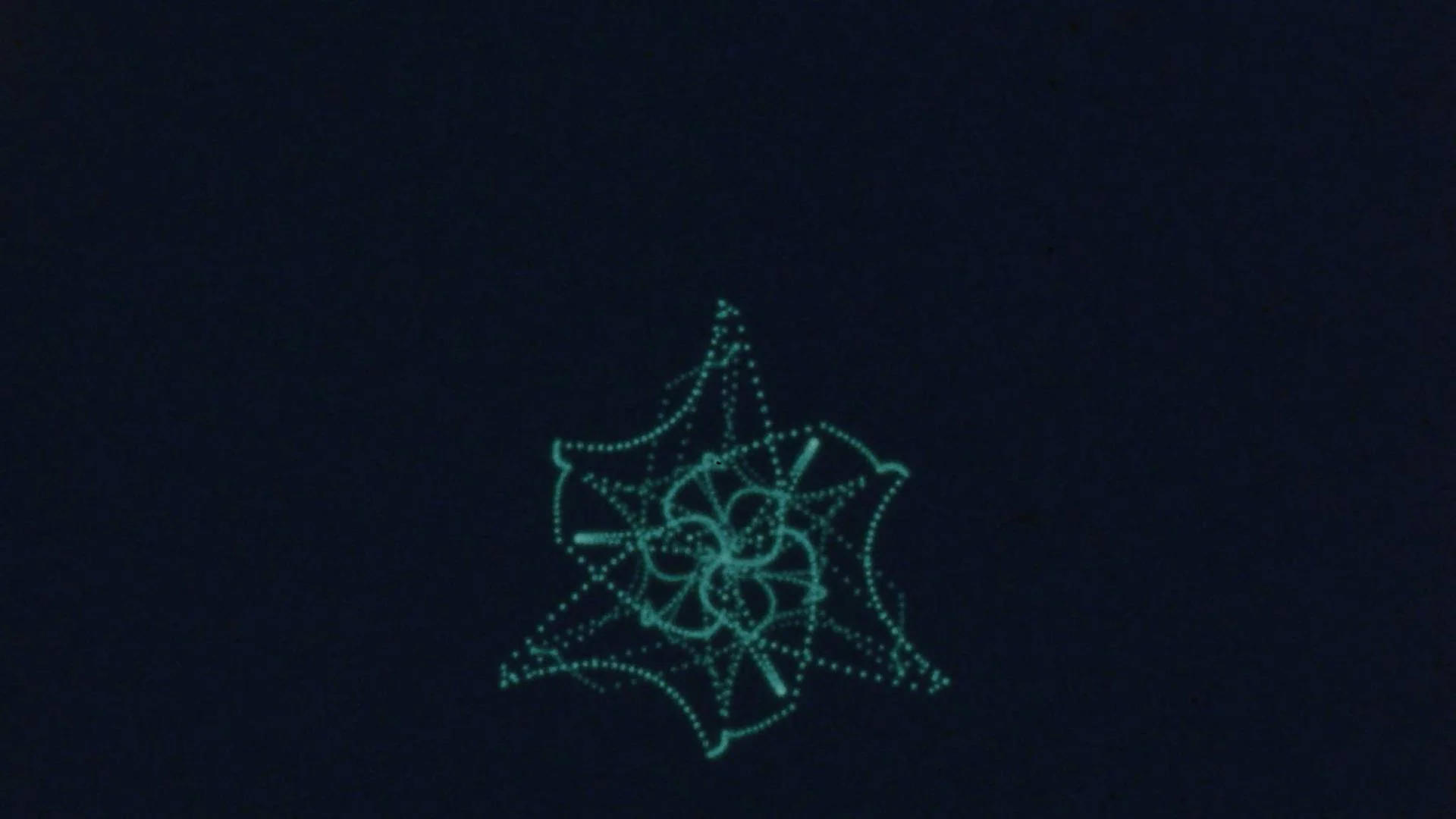

The other is Punto Línea y Simetría (1976) by Gerardo Lastra and Héctor Carranza. This film holds a unique place in the selection as it can be considered the first Mexican digital abstract film. Its significance lies in its exploration of abstract visuals created through digital means, which was groundbreaking at the time. Punto Línea y Simetría showcases the innovative spirit and experimentation within Mexican animation, pushing the boundaries of artistic expression. By including this film, we aim to recognize its pioneering role in digital abstract animation in Mexico and its lasting impact on the evolution of the art form.

Pictured at top: Y si eres mujer

.png)