Louis Zamperini, Hero of Angelina Jolie’s ‘Unbroken,’ Has An Animation Connection

Opening tomorrow, Angelina Jolie’s film Unbroken recounts the true-life story of Louis Zamperini, an Olympian who barely survived a plane crash during World War II, spending a month-and-a-half adrift in the ocean before being captured as a prisoner-of-war by the Japanese. Zamperini’s story seems far removed from anything animation-related, but he did have a significant, and previously untold, connection to an individual who later became an animator.

After competing in the 1936 Olympics, Zamperini joined Coach Dean Cromwell’s all-star track and field team at the University of Southern California. One of his teammates on the team was a high-jumper named Clarke Mallery.

Zamperini identified Mallery and sprinter Payton Jordan as his two “close friends” at USC, and in the late-1930s, they helped lead USC to two national collegiate team titles. Zamperini was especially close to Mallery; a newspaper article of that period called Zamperini and Mallery “inseparable pals.” When Zamperini needed to write a press statement about his withdrawal from an athletic event, it was Mallery and his mother who took Zamperini to a family friend who helped craft his statement.

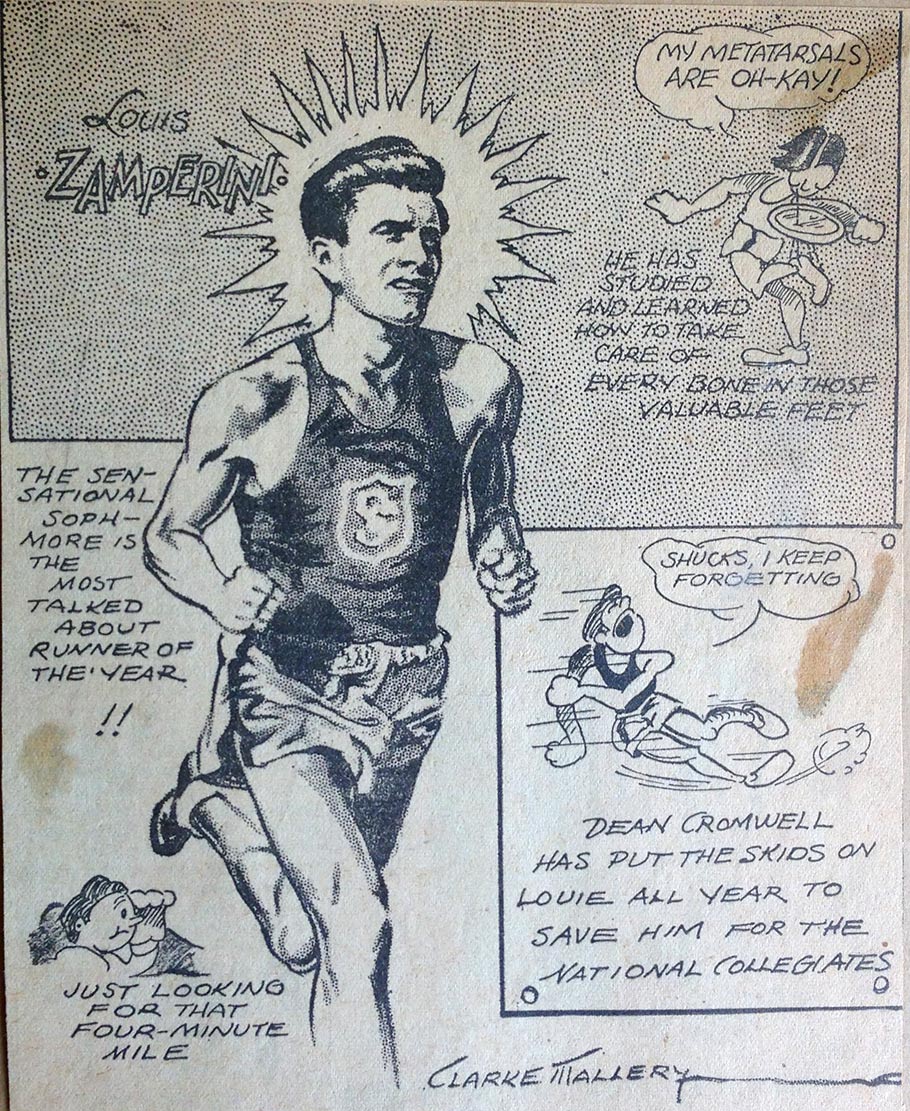

An automobile crash ended Mallery’s athletic career prematurely. Thankfully, for the highly driven Mallery, he had a plan to fall back on. For he was not just a star athlete, but also an artist. Throughout his college years Mallery had drawn illustrations for local Los Angeles papers, and his artistic skills paved the way for an animation career. He was hired at Disney around 1940.

Mallery often drew comics and illustrations of his athletic teammates, including this one of Zamperini:

Mallery and Zamperini’s careers pulled them apart following their collegiate years. Zamperini’s is now the subject of Jolie’s film. Meanwhile Mallery worked as an assistant animator at Disney for much of the 1940s. He was especially proud of one of his earliest assignments, working on Mr. Stork in Dumbo. By the mid-1940s, Mallery had become one of Ward Kimball’s key assistant animators.

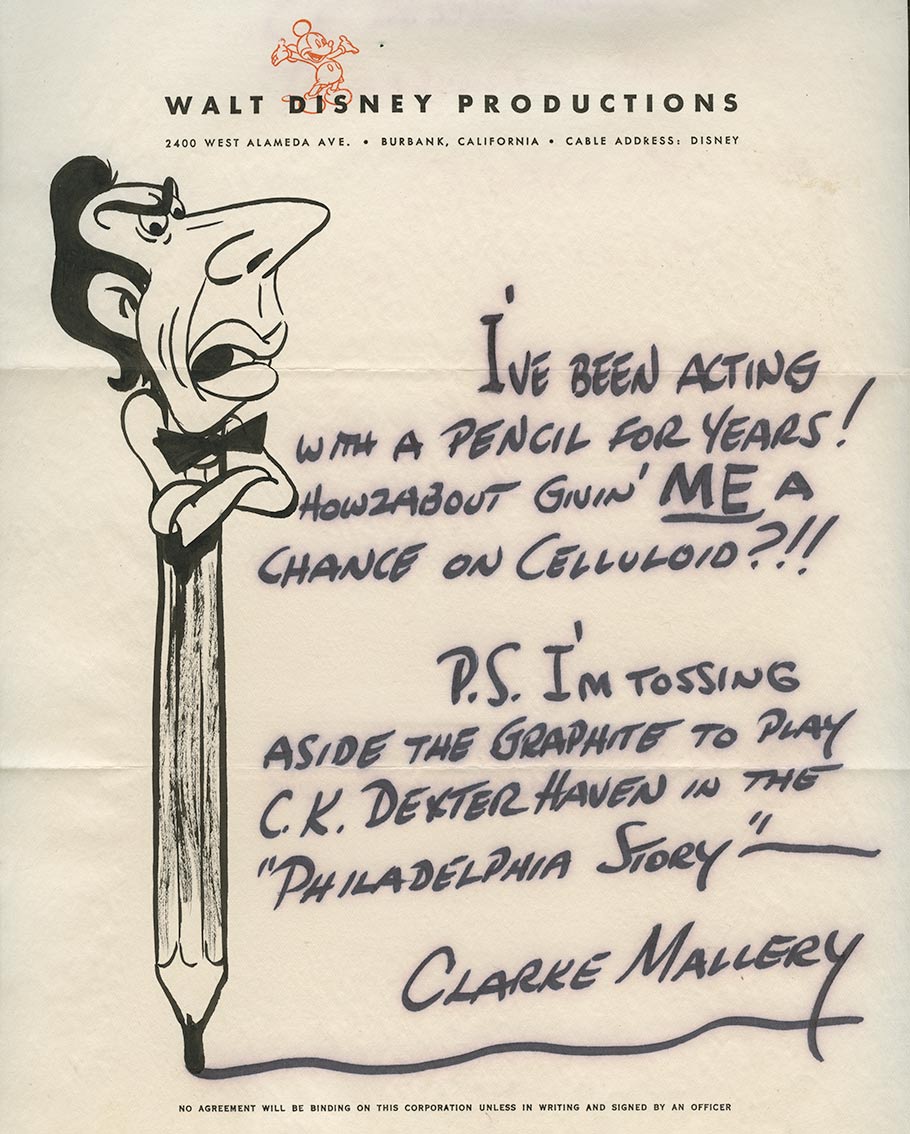

Mallery was a performer in every respect. He acted in theater plays and tried for a long time to break in as an actor in Hollywood. Here’s a letter he wrote to a Hollywood agent in the mid-1940s, after he landed a role in a theater production of The Philadelphia Story:

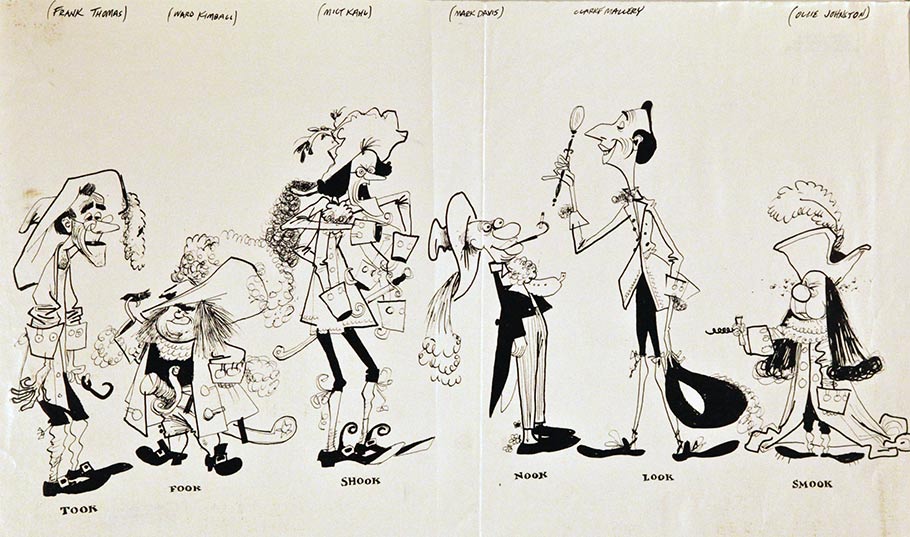

Mallery was also a musician, and Ward recruited him to become the clarinetist in his band The Firehouse Five Plus Two:

Mallery had been promoted from assistant animator to animator by the time he left Disney in the early-1950s. He later worked at studios like UPA and Hanna-Barbera. There’s a whole lot more to his story, which will be told someday in my Ward Kimball biography that the Disney Company doesn’t want you to read.