John Lautner, Architect Of The Greatest Animation Studio Building Ever Built, Was Born On This Day

When Walt Disney built a new animation studio in Burbank in 1940, it cost millions of dollars. Nine years later, when the cash-strapped upstart Modernist animation outfit United Productions of America (UPA) built a new studio a couple miles away, it was done on an “absolutely rock-bottom” budget of around $30,000. It was here that characters like Mr. Magoo and Gerald McBoing Boing came to life, and classic films like Rooty Toot Toot, The Tell-Tale Heart, and The Unicorn in the Garden were produced.

UPA’s studio was made possible thanks to architect John Lautner, who was born on this day 110 years ago. Despite having passed away in 1994, Lautner remains an iconic figure in Los Angeles architecture, mostly on the basis of his residential homes, which still impress for their technical mastery and singular sense of design. A favorite of filmmakers, his daring homes have been used as locations in numerous films, including Twilight, Diamonds are Forever, Less Than Zero, The Big Lebowski, Lethal Weapon 2, and A Single Man. Other filmmakers have used his work as inspiration for imaginary homes, like the Stark Residence in Iron Man and the Parr home in Incredibles 2. His renown is such that he was even name dropped in Dua Lipa’s recent song “Future Nostalgia.”

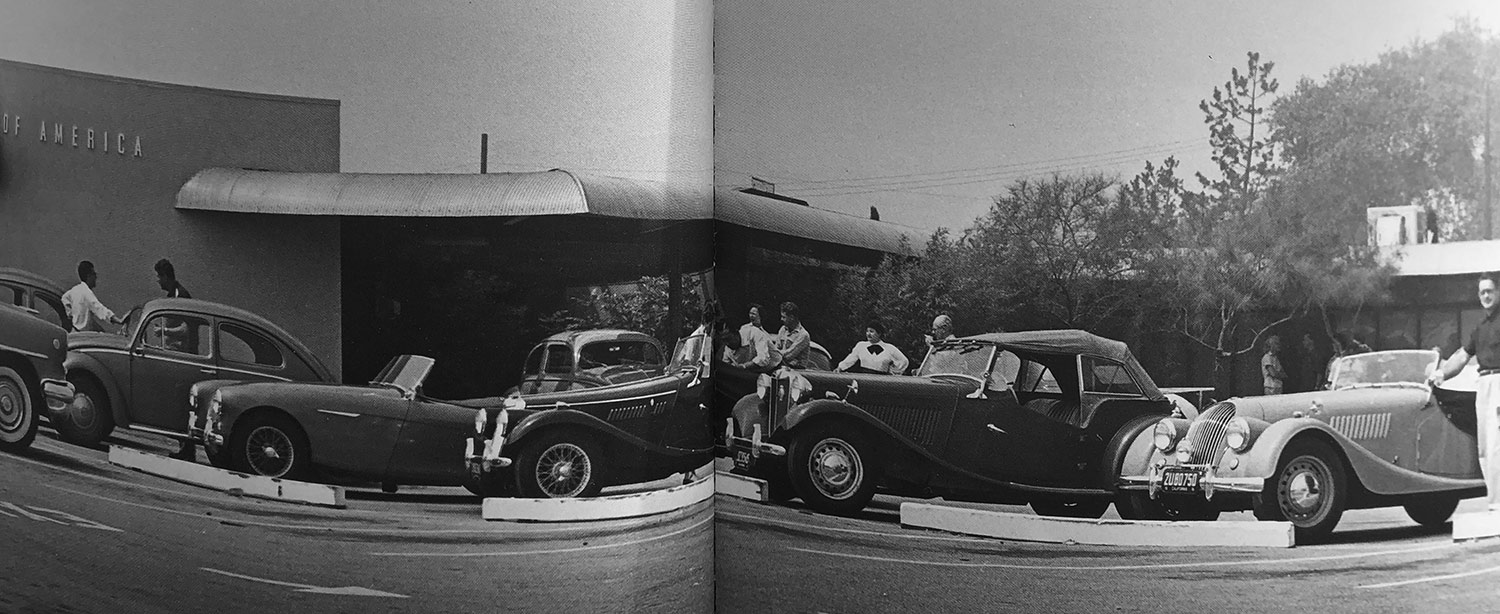

But back to UPA: Lautner was commissioned in 1949 to build the animation studio at 4440 Lakeside Drive, right next to the Smokehouse in Toluca Lake and a stone’s throw from the Warner Bros. lot. UPA, which was formed by ex-Disney artists, attempted to differentiate itself from Disney in all facets of its existence, and the company’s physical location was no different.

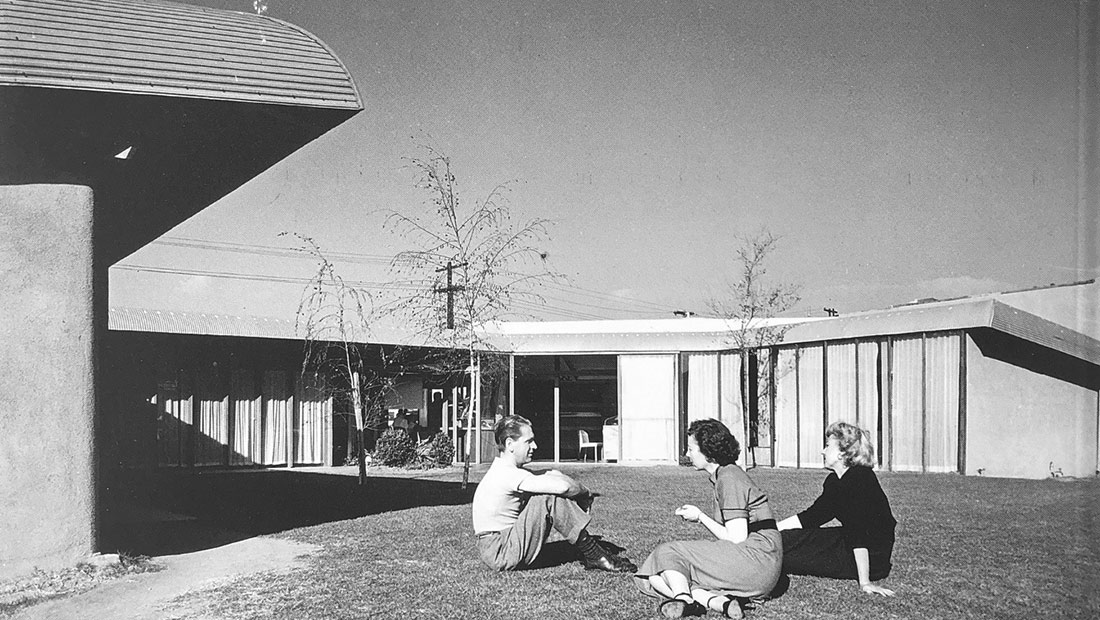

Disney’s massive three-story eight-wing animation building was described by one artist as being “like a combination colossal maternity ward, World’s Fair administration plant and Alcatraz – all pretty austere and unfriendly.” UPA wanted to go in the opposite direction: a single-story building that was surrounded by open space and the concrete Los Angeles River running behind it.

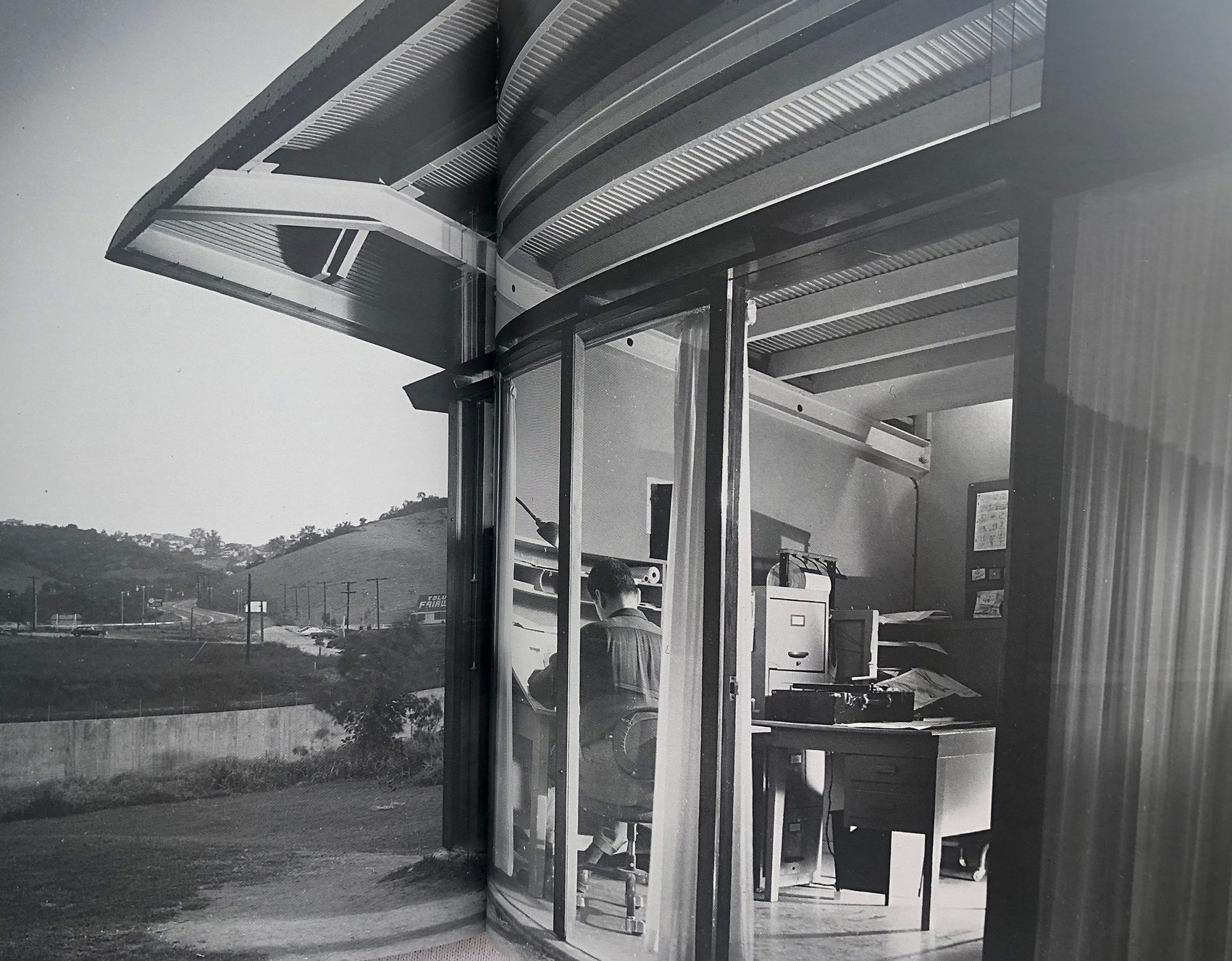

Lautner, an apprentice of Frank Lloyd Wright, was a proponent of organic architecture, and the UPA building was a modest and gentle building that reflected the values and aspirations of the artists who worked within its walls. Far from being a monolith, it was a fluid and light structure that achieved warmth and distinction through a mix of traditional and modern materials: steel, wood, corrugated aluminum, and concrete.

Lautner spoke about the building in a 1986 oral history project, in which he explained the building’s genesis and how the limitations of UPA’s budget inspired him to get creative:

Steve Bosustow, who was the president for years and really the running force of the UPA Studios, saw my house, the first house I did in 1939. And it was about ten years later he came to me because he remembered that house. He loved the house, and he knew there was something there. So that’s how I got the job, which is the way I’ve been getting work ever since, is from the work that I’ve done.

So he came, and they had no money. So he said, “Can you,” you know, “get us, like forty artists’ rooms” and all this kind of stuff that they need, “for thirty thousand dollars?” or something like that.

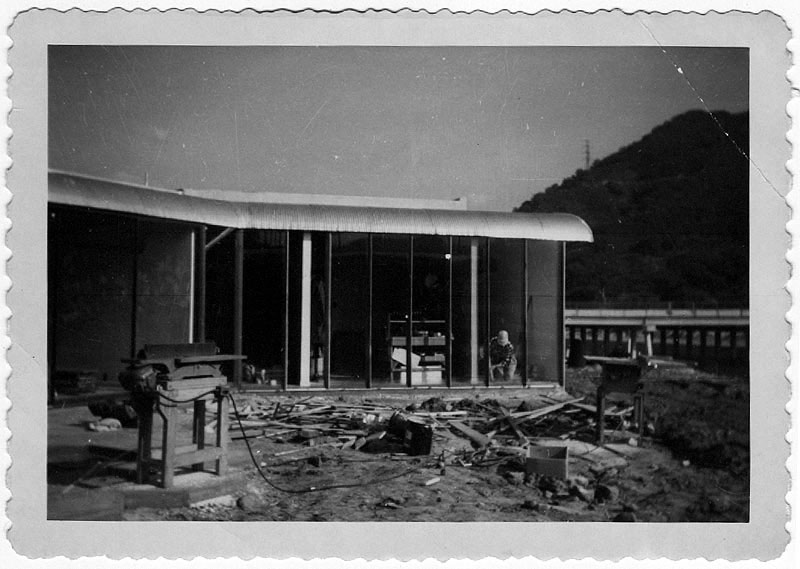

I said, “Well, I don’t know, but I’ll try.” So my challenge there was to get a decent artist’s working space for absolutely minimum money, and I did. I did a rigid steel frame which was minimum structure, and then the whole roof was corrugated aluminum, which was the ceiling as well. So there was no duplication of anything. And because of the way it was detailed – I detailed it [with] a curving, overhanging fascia, that made a very good looking building. And it was absolutely rock-bottom – like a garage, almost-construction. Then, a radiant-heated concrete floor, and so it was a very successful thing. It’s still operating, but it’s been added [to] and remodeled and all that.

The studio wasn’t just a success in Lautner’s opinion. UPA artists loved it too. Everyone who worked in the building remembered it fondly years later as a place where ideas flowed naturally and creativity flourished. While UPA’s glory days didn’t extend past the 1950s, for those who experienced working at the studio in its prime, it was a magical experience that would never be replicated elsewhere.

Sadly, unlike many Lautner buildings that have been lovingly preserved, the UPA studio remains alive only through photos. Disney’s nephew Roy Disney Jr. tore it down in 1983 so he could build an undistinguished office building for his investment firm Shamrock Holdings. But today, we can look back on it and remember that animation studios don’t need to look like generic office buildings where businesspeople work. Besides being functional for the purposes of production, an animation studio also has the capacity to be as beautiful, visually stimulating, and creative as the work produced inside of it. Lautner’s UPA studio serves as a model for how it can be done.

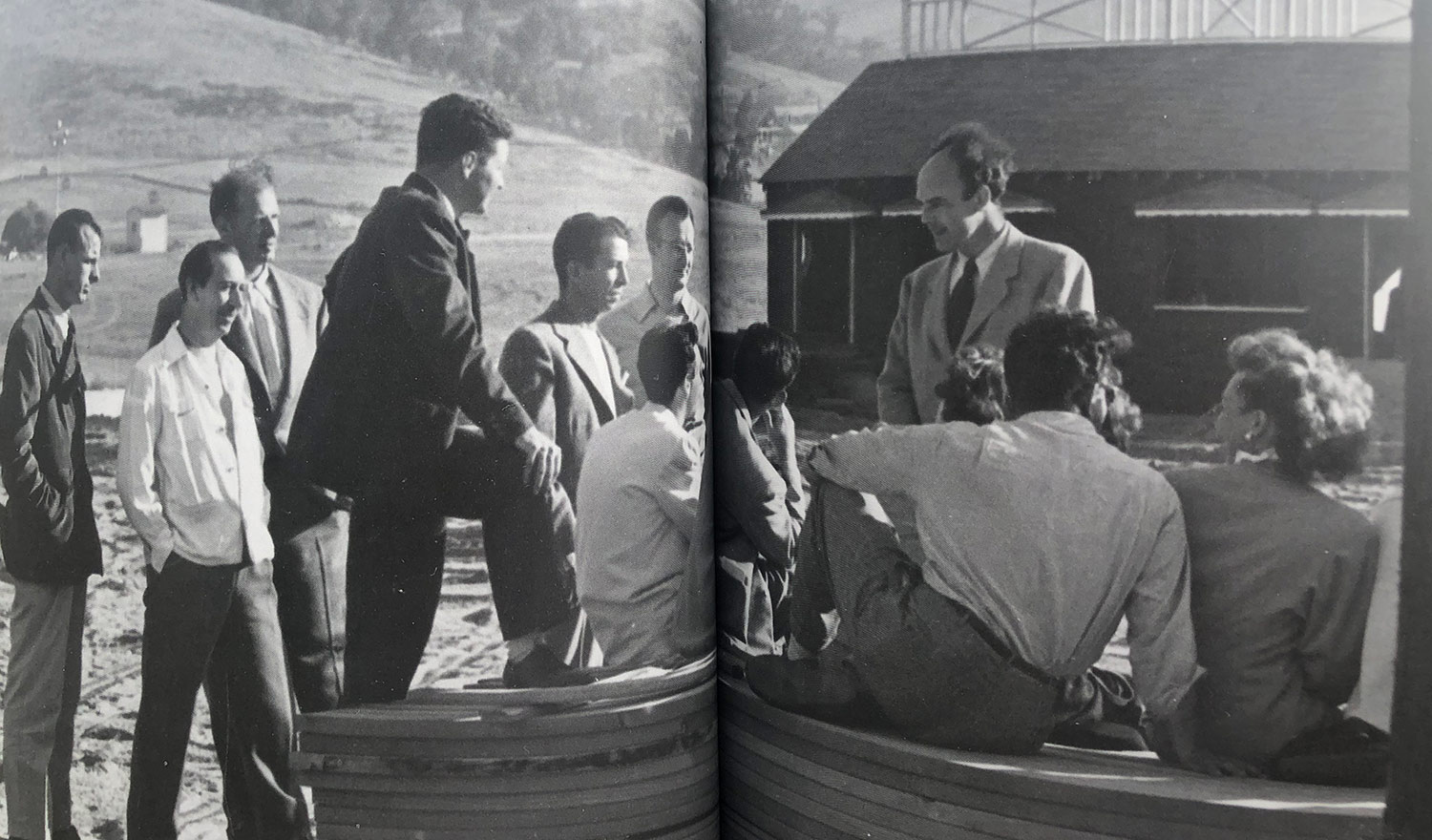

Here are some photos of the UPA studio during its construction and after it was finished: