Have Fear, Five Animated Horror Classics Are Here

With Halloween upon us, the hordes of humanity are turning their attention to ancient favorites from the history of horror.

For the benefit of those seeking essential October viewing, here are five of Cartoon Brew’s favorite animated horror classics, based upon the literary works of Edgar Allen Poe, Franz Kafka, and more. They emerged long ago from the brains and guts of some of animation’s finest talents. Feast!

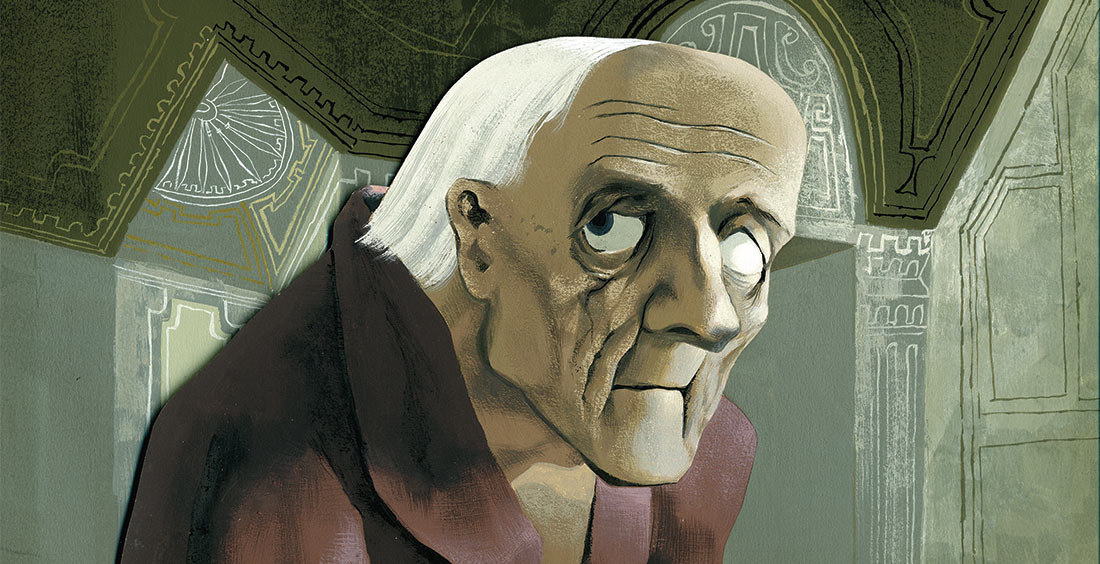

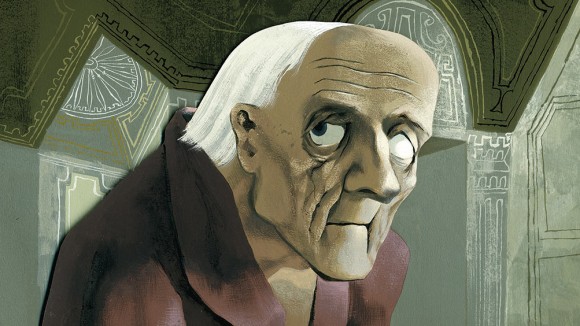

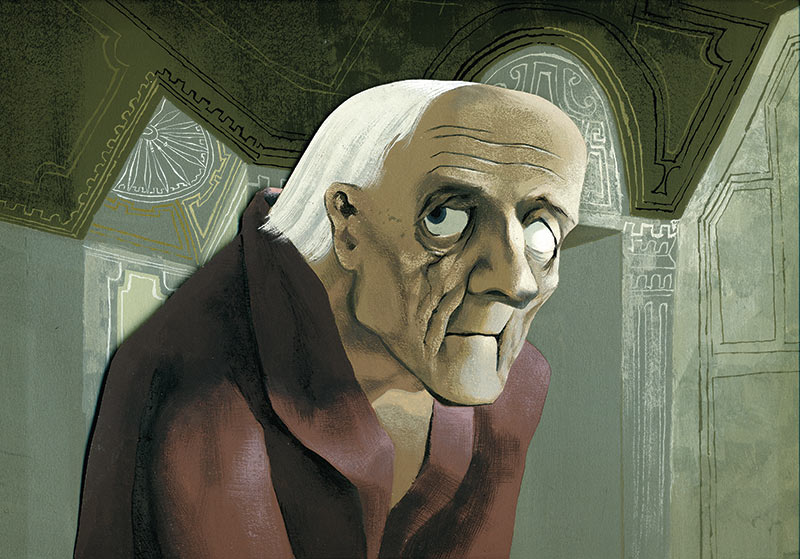

The Tell-Tale Heart

Directed by Ted Parmelee (1953)

Based on the story by Edgar Allan Poe (1843)

Poe’s stories have a checkered relationship with cinema. Many filmmakers have tried their hands at adapting Poe for the screen, mostly to find he is not cut out to be stretched to feature-length. At their best, films based on Poe’s stories manage to capture their spirit, if not their letter. At worst, they swipe Poe for name recognition.

If you’re looking for a Hollywood adaptation of a Poe story that nails its source, then look no further than UPA’s The Tell-Tale Heart.

Using animation’s non-literal potential, UPA’s adaptation is able to show the world through the eyes of Poe’s madman. We never see him, only his vision of a distorted and unsettling landscape that eventually plunges into nightmare.

UPA’s short seems to have been influenced by the iconic illustrations of Harry Clarke. In his visualization of Poe, Clarke depicts the killer as a wild-eyed figure in a strangely organic building, with floorboards hiding a body bearing the chessboard pattern, an element which turns up again when the killer hides the body under a chessboard-patterned blanket.

The Tell-Tale Heart pulls off a neat trick. Taking animation to new and unusual places, it still remains true to its literary roots.

“The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad

Directed by Clyde Geronimi and Jack Kinney (1949)

Based on the story by Washington Irving (1820)

Washington Irving’s 1820 story “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” has undergone quite a metamorphosis in the public imagination. Despite some gentle spookiness, it is at the end of the day a comical yarn about a man pulling his collar up over his head to scare off a romantic rival. Irving deemed it light-hearted enough to include alongside “Rip Van Winkle,” yet most today seem to view it as horror, from Tim Burton’s Hammer-influenced adaptation to the current television series, Sleepy Hollow.

The point of transition would appear to be Disney’s animated adaptation, which formed one half of the 1949 anthology feature, The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad. Disney’s adaptation is still played primarily for laughs, but it made significant decisions that helped to nudge Irving’s tale towards horror.

While Disney’s film hints that the Headless Horseman is just prankster Brom Bones in disguise, the implication is nowhere near as strong as is in its source text. Viewers unfamiliar with Irving’s story could easily miss this plot point.

Disney’s Horseman has a pumpkin for a head, as in the original, but here it is carved to resemble a flaming skull. Compare that to the 1922 live-action version, in which a less-than-fearsome Horseman is clearly brandishing a vegetable. In addition, Brom Bones’ musical number establishes that the Horseman is looking for a victim to decapitate. This gruesome element is not found in Irving’s story, but it became a mainstay in more macabre adaptations, such as Tim Burton’s Sleepy Hollow feature.

Disney did a good job of transforming a ghostly character who could have been a joke, such as in Ub Iwerks’ 1934 cartoon, into an enduring slice of family-friendly horror.

The Castle of Otranto

Directed by Jan Svankmajer (1977)

Based on the novel by Horace Walpole (1764)

Although significant in the history of literary horror, Horace Walpole’s 1764 gothic novel The Castle of Otranto has badly aged. Few today will be chilled by a haunted house whose ghost materializes as a giant foot.

That said, Walpole’s clumsy supernatural imagery can still be spun into gold by a filmmaker with a good handle on the strange. Enter Jan Svankmajer.

Svankmajer’s 1977 short includes a potted adaptation of the novel, animated in Terry Gilliam-esque cutout using illustrations from a nineteenth-century edition of Walpole’s book. However, Svankmajer avoids a simple retelling of his source, and anyone who has seen his films knows of his fondness for found objects. Which is essentially how he adapts Walpole’s novel, as a found object in a larger work.

The main body of Svankmajer’s short is a live-action mockumentary about a researcher who claims to have found the exact location of the events described by Walpole. The film switches between these two strands until fantasy and reality collide, in a climax that would make Charles Fort proud.

The Metamorphosis of Mr. Samsa

Directed by Caroline Leaf (1978)

Based on the novella by Franz Kafka (1915)

Leaf’s film is another fine example of using animation to convey the more subjective elements of a literary work that live-action might struggle with.

Kafka’s story revolves around a man who has turned into a giant insect, an idea with obvious potential for a horror film. But transforming Gregor Samsa into something too grotesque would miss the point of the story; he is meant to be a sympathetic everyman. As illustrated in Leaf’s delicate paint-on-glass animation, the insect Samsa, whose convincingly insect-like appearance recalls the movements of silent cartoon characters, is perhaps even endearing.

Leaf’s film also plays with our sense of space, as characters and locations freely fade in and out of another in sparingly used cuts. The overall effect is claustrophobic, anchored by confined characters inhabiting a small location. Leaf’s film also examines the feeling of loss of control, as its world shifts around its characters, no matter how hard they try to stabilize it.

Samsa’s family conquers its initial fear and comes to accept his transformation, only to gradually give up on him. That foundational fear of abandonment is more cerebral than the typical horror flick.

The Fall of the House of Usher

Directed by Jan Svankmajer (1980)

Based on the story by Edgar Allan Poe (1839)

“The Fall of the House of Usher” contains one of Poe’s favorite themes: the premature burial. Most directors would use it as their central image, but Svankmajer instead situated the film on one of his personal favorite themes: Roderick Usher, the tragic central character, believes that the stones and plants on his estate are sentient, a hypothesis that is seemingly borne out when Usher’s death is followed by the collapse of his mansion. Svankmajer takes this idea as the starting point of his film, which does not show a single human character.

As the film’s narrator reads Poe’s story, Svankmajer’s wandering camera finds deep fascination in inanimate objects, from the stones of the mansion’s walls to the flaking varnish of a household chair. This being a Svankmajer film, the inanimate quickly becomes animate. A stone slides itself from the wall and drops to the ground below. A lump of clay is kneaded by unseen hands, while a coffin slides itself into a crypt. Finally, as the house crumbles, the furniture scrambles out of the building like rats abandoning ship.

Those intrigued by Svankmajer’s interpretations of Poe should also have a look at his live-action short, The Pendulum, the Pit and Hope.