An Appreciation of Chuck Jones’ ‘One Froggy Evening’ On Its 60th Birthday

Sixty years ago on this day — December 31, 1955 — a short masterpiece was released into movie theaters: Chuck Jones’ One Froggy Evening. No one said anything at the time because hardly anyone ever said anything about animation at the time.

Eventually the short gained due recognition. “The Citizen Kane of animated shorts,” Steven Spielberg once called it, but even if Spielberg had remained silent, this wordless wonder would still qualify as one of the finest of Jones’ couple of hundred Warner Bros. shorts.

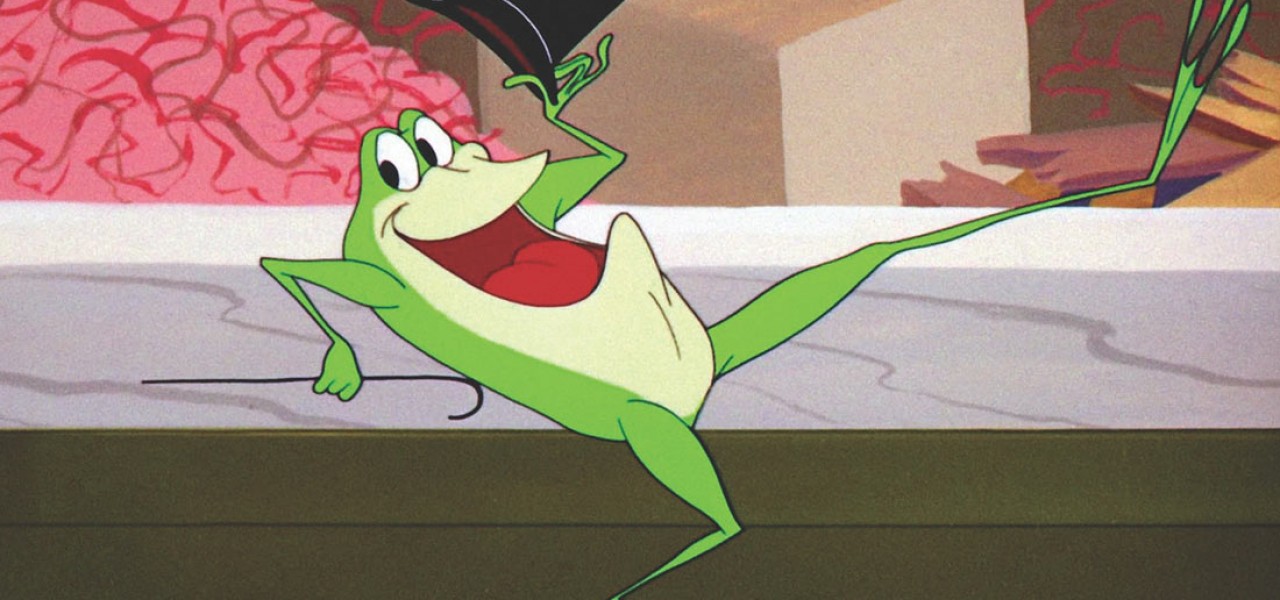

Before we proceed any further though, here’s an excerpt:

Let me admit: as many times as I’ve watched this film, I still cannot understand how it was made. Technically, I get it, but there’s something else going on that is impenetrable. Every member of Jones’ team is operating at the peak of their craft, a level achieved through decades of toil and refinement, yet their collaboration is so seamless and absolute that it does not seem possible for the cartoon to have been created by mere mortals. As the skies above us and the ground below us, this cartoon is a perfectly formed natural wonder that cannot be improved upon.

The credit is due to a few handfuls of individuals: Michael Maltese’s story structure reveals just enough but not all of the mystery; Abe Levitow, Richard Thompson, Ken Harris, and Ben Washam bring the characters to life through perfectly timed and funny animation (it’s funny because it’s perfectly timed); the layouts of Bob Gribbroek and background paintings of Phil DeGuard drop us into the middle of a believable mid-20th century American metropolis. And let’s not forget the musical stylings of Milt Franklyn, the sound effects of Treg Brown, and certainly not the voice of Michigan J. Frog himself, Bill Roberts.

And consider this: Jones’s crew made a new short every three weeks or so. These guys didn’t labor over this film for years, and they certainly didn’t have time to reflect or be precious about it. They simply churned it out, as they did countless others, over and over again. Lather, rinse, repeat, and eventually retire.

But it is director Jones himself who reminds us why he is considered one of animation’s greats. The presence of Jones, who created more layout drawings per film than almost any other Golden Age theatrical short director, can be felt in every frame of the film. Jones doesn’t rely on standard poses or stock expressions; he is a cartoonist of the highest order, a master of his universe, and he effortlessly creates custom poses and expressions for each and every scene, in his inimitable style that can only be described as Jonesian.

Jones’ advantage is that he has something most comedy animation directors, then or now, don’t have, which is an obsession for detail. When he couldn’t find the proper ragtime tune for his singing frog, he wrote his own from scratch with the help of Maltese, resulting in “The Michigan Rag.” The song sounds so authentic that to this day people wonder which songs in the film were pre-existing and which were created specifically for the film (this site explains it all).

His gift for observation extended to his amphibian star. As a frog owner myself, I’m routinely annoyed when animators don’t take the time to get frogs right. When a frog swallows his food, his eyes sink deep into his head. Few animators seem to notice this. But there is no such laziness in Jones’s work. “I remembered from when I was a kid,” Chuck Jones once explained. “Any boy that’s ever picked up a frog knows how the body sits and the limbs hang down. So we had to be certain, in those first few seconds on the screen, that when [Michigan] appeared he looked like a frog. Even that his eyes blinked upward.”

Perhaps audiences didn’t notice every single directorial choice that Jones made during the course of the production. Eyes blinking upward certainly won’t make or break any cartoon. But it’s a reminder that any film, animated or otherwise, is a collection of hundreds upon hundreds of individual creative choices, and all of these choices eventually add up into what the audience experiences on the screen. When an audience views a film, they don’t consciously tally the merits of each of these choices, but they feel these choices and they intuitively understand one thing: Whether the director cares or not.

Jones cared. He obsessed. And in this rare instance, he made all the right choices, resulting in a flawless creative gem.

Frankly, I’m content with the fact that I may never understand how he and his crew made it.

.png)