Disney Artists Write Home During WWII

During World War II, dozens of Disney artists were drafted into the US military. Today I’m sharing letters written by three of those artists who served in uniform—Berk Anthony, Carl Fallberg and David Swift. The letters were all addressed to Ward Kimball, who continued working at Disney’s Burbank studio during the war. Not only are the contents of the letters fascinating but also the artists’ writing styles which exhibit a surprising level of literary sophistication. I’ve annotated the letters with some information about the artists as well as references they make in their writing. Please add your own notes if you know any more about what is described in these letters. Click on each image to see the full page.

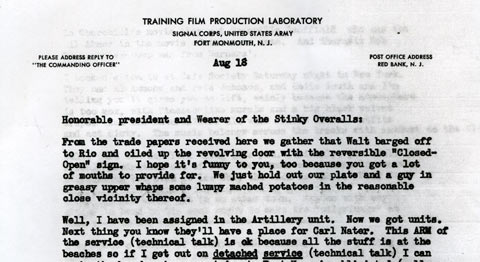

This first letter dated August 18 (presumably 1941) is written by Berkeley “Berk” Anthony. He is a mysterious figure in animation history and I haven’t been able to turn up much about his life and career. He began working at Disney in the mid-1930s. He was Ward Kimball’s assistant for a period of time before David Swift and Tom Oreb took over the assistant spots. I have no records on what he assisted on, but I’m guessing he helped Kimball with Jiminy Cricket in Pinocchio and Bacchus in Fantasia. Anthony also worked in story on The Reluctant Dragon. He was drafted while still working at Disney. I know only two random facts about his post-military career: he designed the Arizona State mascot Sparky the Sun Devil in 1946, and according to a late-’90s interview with Ward Kimball, he committed suicide.

This first letter dated August 18 (presumably 1941) is written by Berkeley “Berk” Anthony. He is a mysterious figure in animation history and I haven’t been able to turn up much about his life and career. He began working at Disney in the mid-1930s. He was Ward Kimball’s assistant for a period of time before David Swift and Tom Oreb took over the assistant spots. I have no records on what he assisted on, but I’m guessing he helped Kimball with Jiminy Cricket in Pinocchio and Bacchus in Fantasia. Anthony also worked in story on The Reluctant Dragon. He was drafted while still working at Disney. I know only two random facts about his post-military career: he designed the Arizona State mascot Sparky the Sun Devil in 1946, and according to a late-’90s interview with Ward Kimball, he committed suicide.

Notes about Berk Anthony’s letter: In the 1st paragraph, Anthony makes reference to Walt Disney’s trip to South America, which was happening during the time this was written. In the 2nd paragraph, Anthony mentions Carl Nater, who was the production coordinator for military films at Disney. (Nater later became the director of Disney’s 16mm film division and tried to suppress the release of Kimball’s Mars and Beyond to schools because he felt it “promoted evolution”.) In the same paragraph, Anthony also mentions his college background. If it’s not evident from his writing, he had an intellectual bent, and having seen a photo of the library in his home, it is also safe to assume that he was well read. In the 3rd paragraph, I interpreted one of his sentences to mean that he appeared in the live-action portions of Reluctant Dragon. I don’t have time to check the entire film right now but should anybody wish to search for him, I’ve included a photo of Anthony above from January 1939, dressed up for a costume party. In the 8th paragraph, he references Hardie Gramatky, the former Disney artist who became a well-known fine artist and author of the Little Toot series.

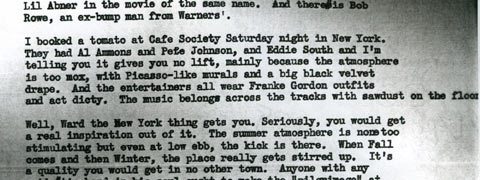

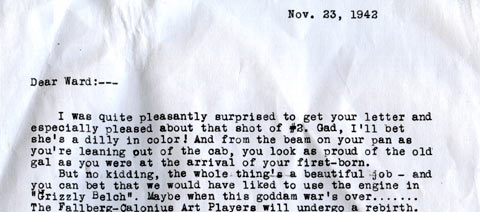

The next letter, dated November 23, 1942, is from Carl Fallberg who was stationed in Quantico, Virginia as part of the Marine Corps film unit:

The unit housed an impressive group of people including not only the animators that Fallberg mentions in his letter but also actor Tyrone Powers, director Richard Brooks and the future Abstract Expressionist painter Richard Diebenkorn. In the 1st paragraph, Fallberg thanks Kimball for the shot of #2, in reference to the train that Kimball was restoring at his home. In the 2nd paragraph, Fallberg references a live-action feature that he had made with fellow Disney animator Lars Calonius. The one hour and fifteen minute Western parody was partly shot at Kimball’s home using his #2 train, the Emma Nevada. In the 4th paragraph, Fallberg lists the Disney artists at Quantico at the time of the letter, who were Ralph Chadwick, Keith Robinson, Walt Smith, Charles McElmurry, Art Babbitt, Nicholas J. George, Don Lusk and Jack Whitaker.

In the 5th paragraph, he says that Frank Thomas was being considered for the unit; Thomas eventually ended up directing animation in the First Motion Picture Unit of the Air Force stationed in Culver City, California. As Fallberg states in this paragraph, Disney layout artist Tom Codrick would become the head of the animation unit in Quantico. In the 6th paragraph, he thanks Ward for giving animation pointers to his sister Elinor Fallberg. In the 9th paragraph, he writes about visiting his live-action filmmaking partner, Lars Calonius, who was in the Army’s Signal Corps film unit further north on the East Coast. (Calonius stayed in New York after the war and ran a successful TV commercial studio for many years.) In the 12th paragraph, he references G.F.R.R.–the Grizzly Flats Railroad–which was the official name of Kimball’s backyard.

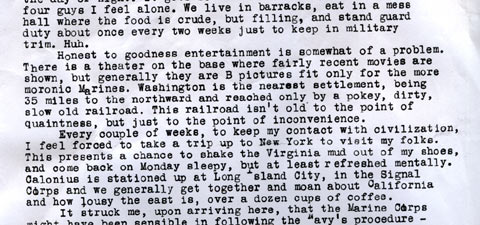

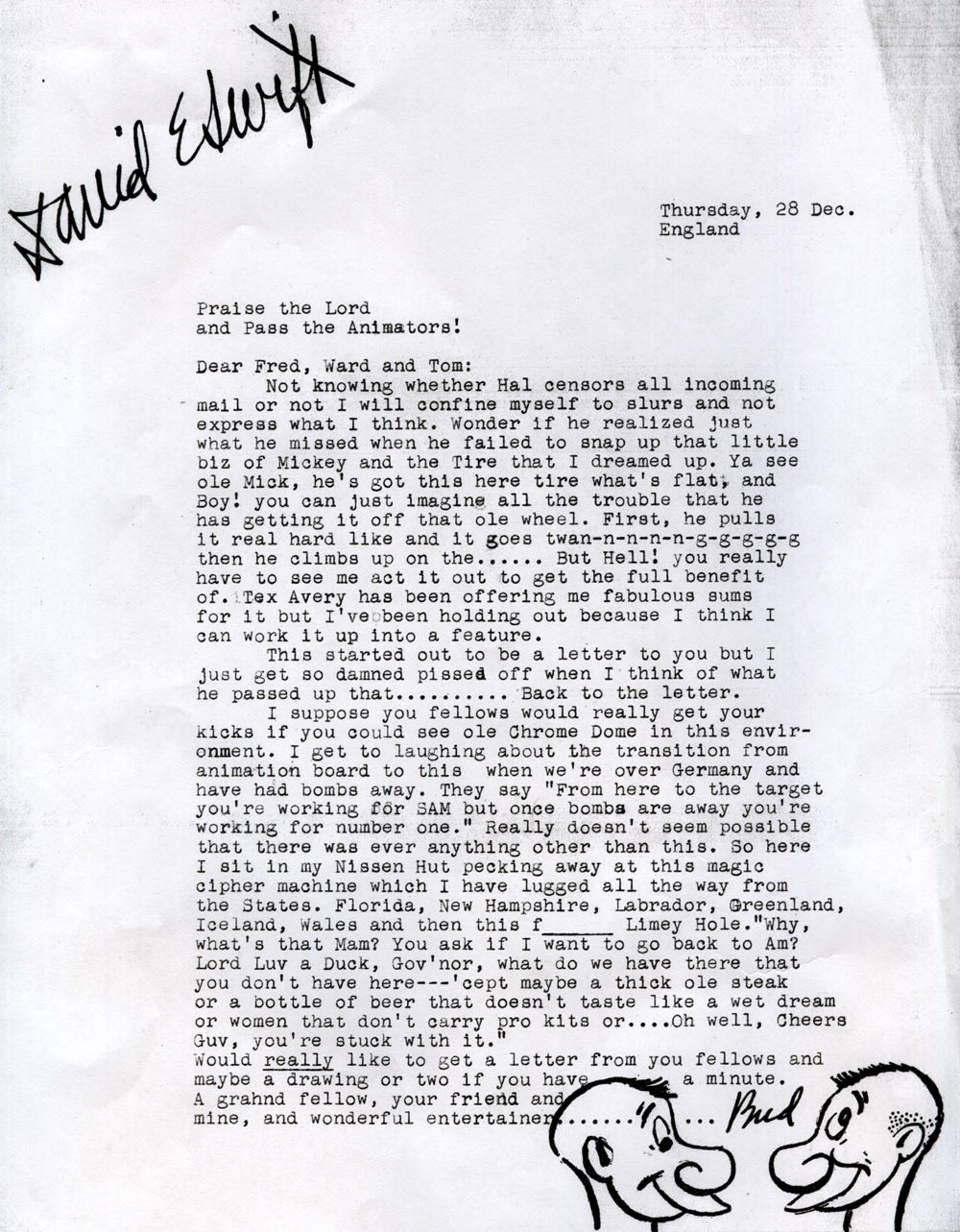

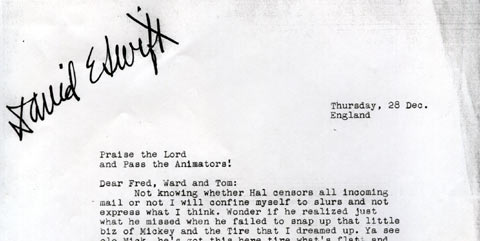

The final letter is from December 28, 1945 from David “Bud” Swift, who was Kimball’s top assistant on Dumbo, The Reluctant Dragon and Education for Death among other projects.

Swift’s letter, written from England, is addressed to Fred [Moore] and Tom [Oreb] as well as Ward. Unlike Anthony and Fallberg who were working in film divisions during World War II, Swift was flying a B-17 Flying Fortress in the Air Force. In fact, he flew thirty-four bombing missions into Germany in 1945; the Germans had already surrendered by the time he wrote this letter. In the 1st paragraph, Swift’s mention of “Hal” refers to Hal Adelquist, the head of Disney studio personnel. In the 3rd paragraph, he writes that he wished he were back in the States, where women didn’t “carry pro kits.” A description of pro-kits can be found in this book excerpt on Google Book Search. Swift has a way with words, and after the war, he became a writer at Warner Bros. Later, he created the TV series Mr. Peepers and directed features like The Parent Trap and How to Succeed in Business without Really Trying.

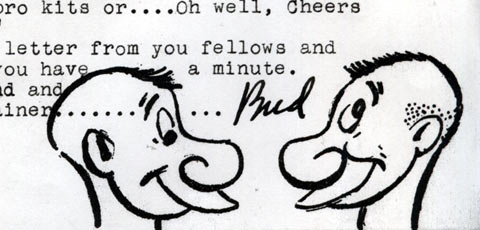

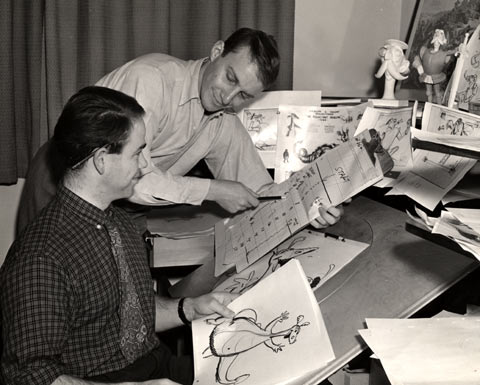

Here is a photo of Swift (standing) and Kimball during the production of The Reluctant Dragon.

.png)