Q&A: Chris Landreth On 20 Years Since He Wrestled With Maya To Make The Strange and Surreal ‘Bingo’

If you’re an early Maya user then there’s no doubt you’ve seen Chris Landreth’s short film Bingo. Now 20 years old, Bingo was made while the director was working at Alias|Wavefront (now Autodesk), which used the surreal film to help test the limits of the then new software. The short caused a stir among attendees when it was shown at SIGGRAPH 1998.

Landreth had already made some pretty way-out films before Bingo, and has continued to do so. His short the end (1995), was nominated for an Academy Award, while Ryan (2004) won the director an Oscar for best short animated film.

Bingo, which was actually an adaptation of a live theater performance called ‘Disregard This Play,’ found its way onto a multitude of Maya demo discs, and early web-streaming sites. It showed users that a complex piece of software could be used for experimental animation and storytelling. With SIGGRAPH 2018 happening this week, Cartoon Brew sat down with Landreth to revisit Bingo – and the accompanying chaotic development of Maya – two decades after its release.

Cartoon Brew: What were you doing right before you started working on Bingo?

Chris Landreth: I had been an animator at Alias for a few years before Maya really started getting developed. I got there in 1994. At that point, Maya was a glimmer in the developer’s eyes — two or three developers at that time. At that point, it was to the side of anything I was working on. The idea was to develop a low-end animation tool, which at that time would have been for Macintosh computers. That was what Maya was originally looking like when I joined Alias in 1994.

Then I did a piece that you may remember called the end with Alias in 1995. That was around the time that Alias was merging with Wavefront under the guise of SGI. PowerAnimator and Wavefront Advanced Visualizer were merging into a single superpower animator product. I was using that version of PowerAnimator. By the point that the end showed at SIGGRAPH 1995, things started changing with the development of what would be Maya. It became decided that, instead of being a low-end product, it should be the ultra high-end product of Alias.

It was at that time that Alias really, really, wanted to get into the animation industry instead of just the design and CAD industries. The first alpha version of Maya, I think, would’ve been late 1996. I managed to convince people at Alias that we should do a really high-end short film with this developing product. I said, ‘Let’s see if we can intertwine them and make both of them happen at the same time’ — both of them to be released at the same time.

Was the plan always for Bingo to be a very ‘Chris Landreth-type’ short, if I can say that? Was it hard to convince the company to do something a bit more subversive and out there?

Chris Landreth: Well, the end was a weird film and non-conventional in many ways, and I look back at the actual people who were in charge of Alias|Wavefront at that time and I’m delighted that they were so receptive to weird stuff. In particular, the guy who was the manager of developing PowerAnimator and then shifted over to Maya, Kevin Tureski, and the guy who was in charge of Alias|Wavefront, Rob Burgess. They were on my side. To my surprise and delight, they were totally into this. Then when I started working on Bingo, Kevin Tureski, bless his heart, was totally my champion. But I did meet a lot of resistance on Bingo because it has this comic, but darkly comic, subject matter.

How did you start piecing out a story for Bingo?

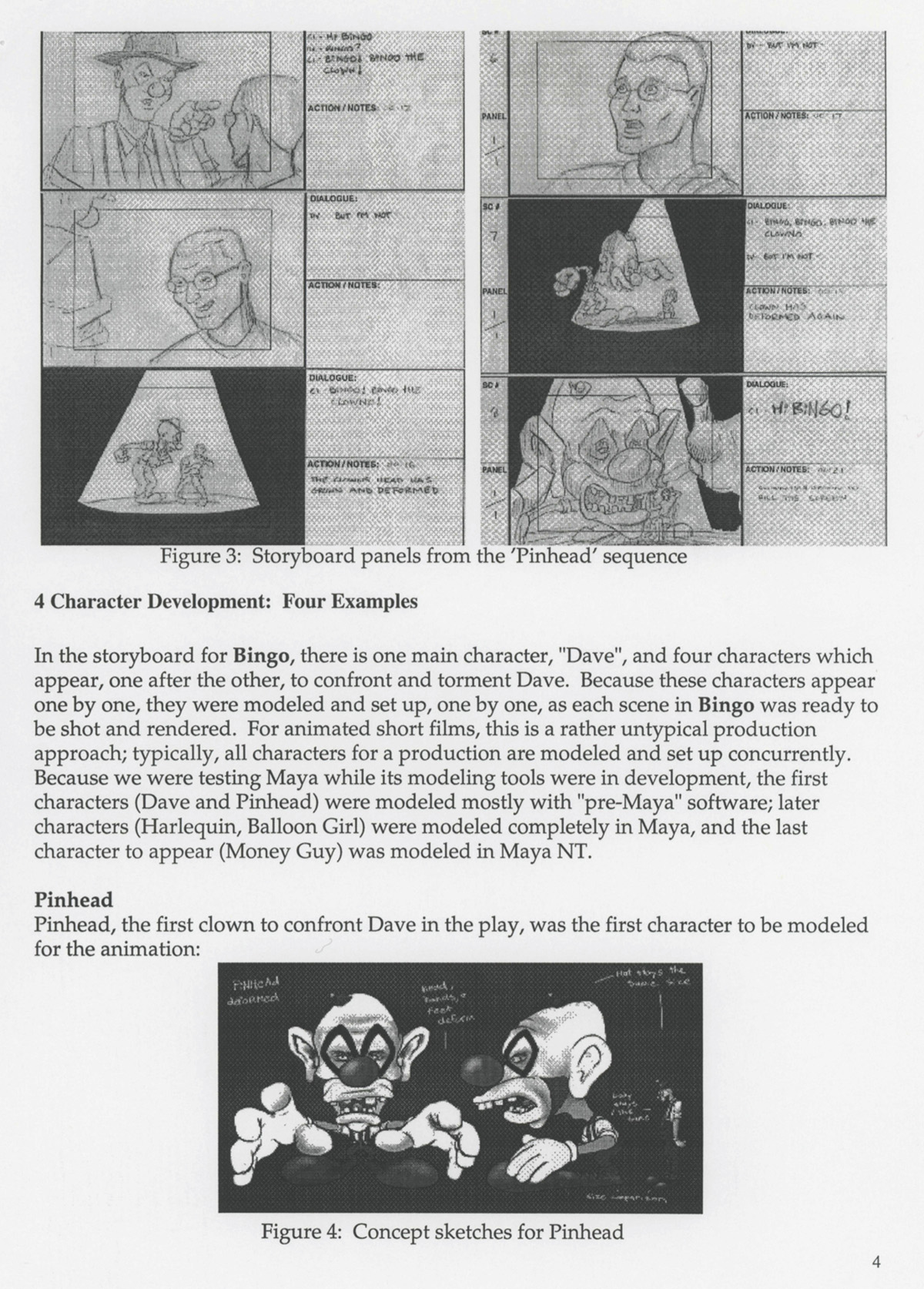

Chris Landreth: The story came pre-packaged for me, because of the fact that it is based on one of hundreds and hundreds of short plays by a group in Chicago, who had a great deal of notoriety, called the Neo-Futurists. I saw them perform many times. The idea for Bingo was their play. It stems from one of their five minute productions called ‘Disregard This Play,’ and it’s basically ‘Bingo the Clown.’ I was inspired not only by the story in that but by the idea that I could do an animated documentary of them performing this play. The voices that you hear in Bingo are actually the Neo-Futurists performing the play onstage.

When I showed this at SIGGRAPH, we actually flew down the performers Greg Kotis and Phil Ridarelli, who are from the group, and they performed the first bit of Bingo onstage. Then that segued into Bingo being performed on a big screen. It’s a very theater-based piece.

When you sat down to make the animated film in Maya, what were some of the first things you were doing?

Chris Landreth: Maya had a development schedule, when I started this, in which the managers were anticipating it would be released within six to eight months. But, no, it turned into an extremely arduous development process, building software as advanced as Maya, basically from scratch, building the core architecture from scratch. Building the way that data flows through Maya, through the thing called the Dependency Graph, is a core architecture that didn’t exist in any form ever before in a software package. At that point, Prisms by Side Effects Software was in parallel doing that.

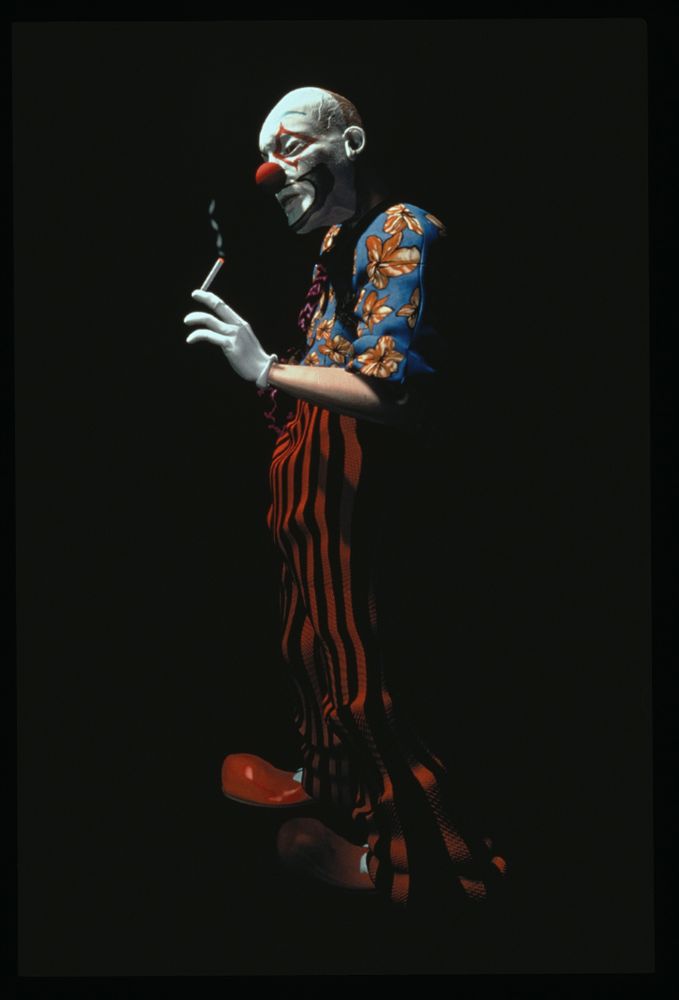

Building that for Maya from scratch meant on my end, the artist end, that I would, say, try to model an ultra-realistic clown and Maya would crash every time I moved a vertex. ‘Alright. So, let’s try something simpler. Let’s try a sphere. Let’s move a vertex on a sphere.’ Maya crashes.

Now, my official job was an expert user, not a filmmaker. My job as an expert user was to fill out bug reports. So, the whole short film Bingo, but particularly within the first few months of trying to do Bingo, instead of real progress on a cool, short film, it instead resulted in something like two or three thousand bug reports filed.

I’d try to model a realistic clown face but Maya kept crashing. Well, why did it crash? Well, I selected a vertex with a swipe, rather than point-selected, and the swipe part of Maya at that point didn’t work, for example. There’s many thousands of examples I could give you. So I’d do a bug report. ‘The swipe-select on Maya doesn’t work.’ ‘Here, try it on this sphere.’ Yeah, most of my bug reports involved, ‘Make a sphere.’

So they were pretty far from actually being able to do a film, and stress is mounting. There’s 120 people on the development team of Maya. It’s a mess. I mean, in hindsight, how it could not have been a mess? The result was that the expected release date went back another two months here, another three months there, and soon it was almost two years past when it was supposed to be out. But by a year into this ordeal, Maya was solid, and it started to get solid in a pretty cool way.

What kind of team did you have working on the film?

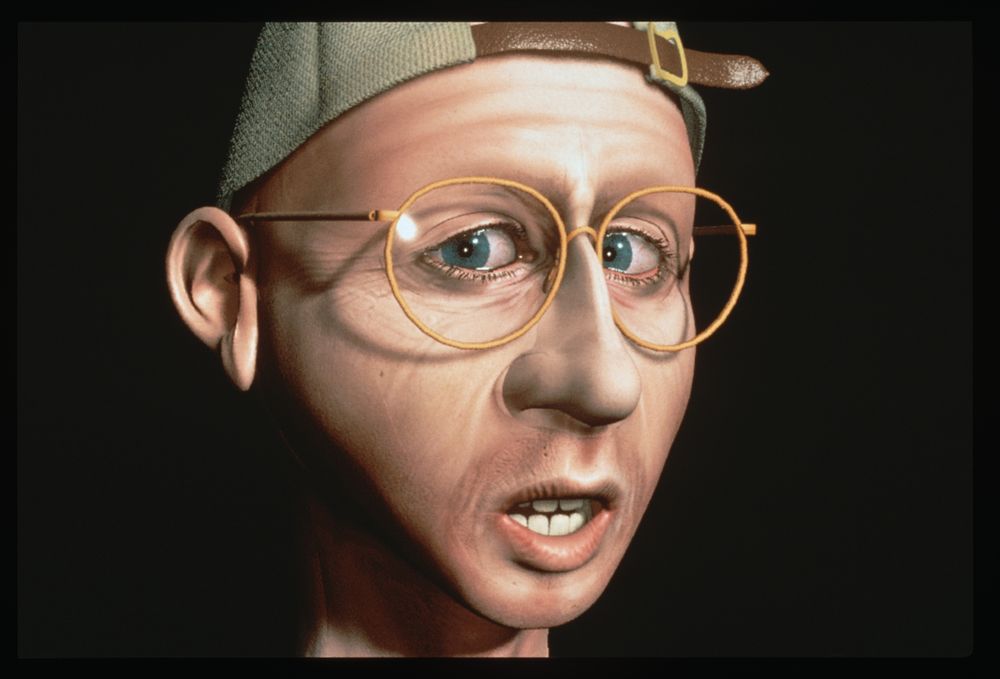

Chris Landreth: A lot of people were involved, but early on I had a team of me and three other guys. Ian Hayden was doing modeling and texturing. Owen Demers did lighting and rendering, and Dave Baas was an animator. Ian, for example, did the entire set – that huge, nightmarish, surrealistic set with the seesaw elephant type features, the video screens that pop up and fold. That was his very demented genius of a set design thing happening there. I would say that for the animation: I probably did about one third and Dave Baas did the other two-thirds.

What do you remember about some of the advancements in Maya that were advantageous to your film?

Chris Landreth: Well, blend shapes was myself and a guy named Karan Singh, who I still work with here at the University of Toronto. The workflow for doing blend shapes was Karan writing the code and me saying what it should do and testing it out.

But man, everywhere you look in character design, rigging, and animation – just a lot of stuff came out of the development from Maya 1.0 from scratch. The use of clusters, what’s called smooth bindings, smooth skin, came out of those early years of Maya development. The various stuff that became simulations. Hair and cloth. Cloth was first introduced in Maya 2.0, so that was six or eight months after the first release. But, yeah, things involving lattices, what was at the time called freeform modelling, things called the wrap deformer – stuff that had not existed in any software package before, maybe in some plug-in or some proprietary software like Pixar’s Marionette, for example, but no, as far as widely available stuff off the shelf, yeah, we were putting stuff in there that wasn’t there before. Yeah, it was way cool to be able to use that in Bingo.

The balloon girl character has a swinging, flowing dress. It was a prototype of what became a cloth simulation – ‘You mean I’m putting this into software that is soon going to be commercially available?!’ Very cool stuff was coming out of that latter part of the development, and it totally exhausted everyone. By the time Maya was released – it was released in the spring of 1998 – and then a week later, Bingo was submitted to SIGGRAPH. By that point, you had a lot of extremely exhausted people.

Tell me a bit about crunch time on Bingo, when you had got up to speed on some of the new tools and you really needed to submit to SIGGRAPH and get it finished. What was that like?

Chris Landreth: Well, you remember the happy moments. What I remember was that, yeah, it was a terribly major crunch to get it done. Six months before we had to submit to SIGGRAPH, Maya started really coming together in late 1997. It was like, ‘This is pretty cool. We’re actually using cool, working software, and we’re making stuff out of this, and we’re animating and being actually artistically creative,’ which was amazing to be able to do that. That made the pain of the year before dissolve because we’re getting shit done. The four of us worked, yeah, pretty fast towards the end. It was a five-minute long piece. We had three minutes done for the submission deadline, and we finished the piece in time.

What was the renderer that Maya had at that time?

Chris Landreth: Maya had its own render, which it still has. You can still use Maya’s renderer. And that was and is perfectly fine in some cases. It had ray-tracing and depth map shadows. It actually was fairly well developed. With respect to the Maya renderer today, the focus went onto third party rendering solutions, like Mental Ray and then now, of course, Arnold. I would say that the renderer came mostly formed when Maya 1.0 was released.

What do you remember about the initial reaction to Bingo?

Chris Landreth: It started getting notoriety. People, much to our surprise at SIGGRAPH ’98, were just going, ‘Hi, Bingo!,’ to each other. That was pretty cool. I’ve been very flattered to think that, yeah, there was an element of the film that suggested that you could do stuff that’s high-end but not necessarily commercial. If that inspired people to think in those terms, I’m happy to know that film contributed to that being possible — that people could think of that as being possible. But at the time, the reaction to Bingo was extremely mixed.

The end, my film before that, I think people generally liked it because it’s funny and a bit more fluffy perhaps. But Bingo has some dark stuff in it. It’s got an element that’s disturbing and uncomfortable. This caused a lot of rejections in festivals and stuff.

I was saying before, I was alluding to the vibe at Alias as being a little bit less warm than it was with the end. Yeah, there was this real sense that, ‘Here’s our flagship product, and we’re going to be putting it out there, and now we’re going to be marketing it with a film about disturbing clowns?’ There was definitely that question about the validity about having a film like this happen. Again, I’m going to give a lot of credit to a person I mentioned before, Kevin Tureski, for championing and defending the production of Bingo from quite a few people who were really anxious about it being out there and the film that it was going to be.

The general vibe was that this is not what you would call a happy piece. It definitely made for a lot of reservation in its being shown and it being accepted. It didn’t win a whole lot of awards, I’ll say that. Not nominated for Oscars and stuff. I think that its enduring appeal was well after it was released. It was probably not until about 2001 or 2002, I started getting the impression that this film is actually not going away despite of the fact that [the reception] was, I would say, lukewarm. But there was definitely reservation about it when it came out.

Much to my surprise and happiness, years kept going by and people still wanted to see it and talk about it, and festivals that had rejected it when it came out were now highlighting it as a big moment in computer animation.

Anything else you wanted to share about your memories of working on Bingo?

Chris Landreth: I’m very proud to have been part of the Maya team. I’m very proud to have a gold-plated cd on my wall. I think it is number 26 of all the pressings of Maya 1.0. It’s still there. I haven’t opened it. I haven’t tried installing it, I wonder if it would work…?

.png)