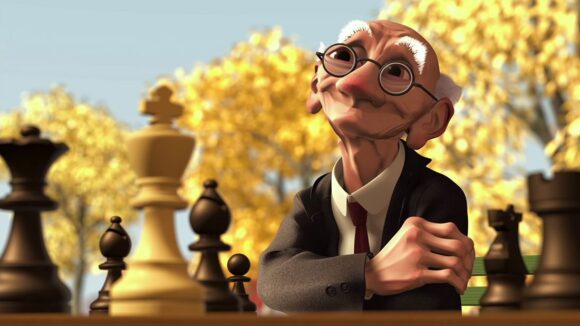

‘Geri’s Game’ Turns 20: Director Jan Pinkava Reflects On The Game-Changing Pixar Short

November 24th marked the 20th anniversary of the release of Jan Pinkava’s Oscar-winning Pixar short Geri’s Game. The short, which would on to play before A Bug’s Life in cinemas, was critically important both artistically and technically in the history of the animation studio.

Geri’s Game tells the story of an old man playing chess against himself. It was the first Pixar short to be released since Knick Knack in 1989. It was also the first Pixar production to feature a human as a main character. And it was the first project to demonstrate the studio’s new advancements in subdivision surfaces.

Now creative director at Google Spotlight Stories, Pinkava would go on at Pixar to conceive Ratatouille before Brad Bird took over the film. Cartoon Brew sat down with Pinkava to discuss the origins of Geri’s Game, how he pitched it to John Lasseter, dealing with a stylized human character, his memories of working on the film, how Giorgio Armani nearly played a part, winning an Oscar, and the short’s 20-year legacy. Pinkava also shares many of his original illustrations and boards for Geri’s Game.

Cartoon Brew: How did you find your way to Pixar, originally?

Jan Pinkava: Well, I came to Pixar because of John Lasseter’s shorts. I remember seeing Luxo Jr. and, like so many people, being inspired by that and thinking, ‘That’s what I want to do.’ I was doing commercials and idents and stings in the Soho graphics biz in London, and I applied to Pixar when it was really unusual to send a show reel and a resume by email. I sent it to Ralph Guggenheim at Pixar, and I ended up at Pixar in 1993 to really replace John Lasseter, Pete Docter, and Andrew Stanton – who’d moved on to pre-production on Toy Story – directing commercials in the Pixar shorts group.

Of course I came there with the hopes of to some extent following in John’s footsteps and to have an opportunity to make a short. Because that’s what Pixar meant to me, besides of course what was going on with this burgeoning feature film, Toy Story.

So I was directing these commercials [Pinkava’s “Arrows” spot for Listerine won a Golden Clio in 1994] but all the time knocking on Darla Anderson’s door – Darla was the executive producer of the shorts group – saying ‘Let’s make a short film, let’s make a short film,’ always suggesting in between projects to do something.

Just after Toy Story hit and everything was changing, and Pixar was going public, and A Bug’s Life was in pre-production, Ed Catmull came to Darla and said, ‘We need to re-start the short film program.’ So the idea was always two-fold: to bring on new talent, to develop new directors and help them grow, and, if possible, to focus on some particular technical development, that is, use a short film to push a technology that needed to be developed.

And at the time Ed identified the technology part of that – we needed to be able to do human characters somehow.

That meant, more expressive faces and the complexities of clothing. These things were really hard to do in the cg medium at the time. I think the perception was that Pixar was in danger of falling behind in that technology. So Ed said to Darla, ‘We need to make a short film, do you have anyone who’s interested in making short films?’ She said, ‘Well, Jan’s been knocking down my door ever since he arrived.’ And so Ed came to me and said, ‘Jan maybe you can make a short film at Pixar if it’s a good story, and it has a human character.’

What was it about doing a human character that was so important?

Jan Pinkava: Well, sooner or later, you have to be able to tell stories with human characters. There are only so many toy, bug, and fish stories you can tell. At the time Pixar was building a whole studio on this new medium of computer graphics. We used to joke there were more PhDs per square meter than anywhere else. A lot of smart guys who invented these techniques were there, and Ed Catmull himself, one of the founding pioneers of the medium. And there was a lot of focus in the cg community on the key challenges — and at the time still in the medium of cg it was all about photorealistic rendering. Our work horse renderer, the thing was called Photo Realistic Renderman, that’s what it used to be called: PR Renderman.

And the goal for most people in cg research was, make it indistinguishable from photos. And similarly in the technical mindset a goal that could be described and understood by everybody was to make realistic synthetic humans. There used to be at SIGGRAPH these workshops about ‘synthespians’, about how to make hair and clothes and skin and articulation of muscles and everything else about actually making a synthetic character. The question was, how can you make a human?

For me, it wasn’t about being real at all, because Pixar is an animation studio. We were doing stylized characters. And this is where my old Czech roots came in. I grew up with Czech animation and Czech puppet theater, and those things are part of the culture of central Europe. In thinking about a human character all I did was simply rip off one of my childhood heroes, Jiří Trnka, the great Czech animator. Trnka was more than an animator. He was especially known and loved by most people in Czechoslovakia as a wonderful and astonishingly prolific book illustrator.

Everyone was raised with storybooks illustrated by Trnka. But his roots were in puppet theater. And of course he made these beautiful short and feature-length stop-motion puppet films because he came from the puppet theater, from actual marionettes, and that’s a centuries-old tradition in central Europe of people designing puppets for the stage. These are mostly human characters, for telling traditional folk tales and so on. Human characters but as stylized puppets.

So I came from an area of Europe where people have been dealing with puppet theater for centuries, and that sensibility and design thinking about stylized human characters was very well established. I wasn’t inventing anything. I was just copying what I was exposed to as a child. It felt obvious that you don’t get into the debate of making human characters realistic, never mind that, that’s a worthy goal but not for the animation studio. You’ve got to figure out a stylization for the character as if it’s a digital puppet.

Years later, Brad Bird told me that one reason why he had taken the offer of coming up to Pixar seriously was that he’d seen Geri’s Game and that was the first time, for him, that someone had made an animated cg human successfully, so he knew it was possible to use the medium to tell a story with humans.

You mentioned that you were told you could do it if the story was good. So how did that pitching process go?

Jan Pinkava: Now, when Ed said, ‘You can do it as long as it’s a good story, and it has to have a human character,’ I actually had drawers full of ideas I’d been working on since I came to Pixar with this idea of making short films. But, weirdly, none of them had a human character! But I immediately said, ‘Yes, of course I’ll pitch something,’ and then I had to go away and think, well what could I do with a human character?

Now, I have a technical background as well, that’s why I’m sort of a weird hybrid person – I was an animator as a kid, and then got a technical education and did a computer science degree and then a PhD in robotics, but I was always doing technical projects for pushing things towards graphics and being fascinated by this new medium.

So when it came to a human character, I realized straight away it was just going to be technically hard. It was going to be challenging. We were going to be doing difficult new stuff. The two main challenges that we needed to explore in this short were skin and cloth.

Luckily we had Tony DeRose and Michael Kass, they were the two main researchers on the project. Michael was a math genius doing the cloth dynamics simulation, which was far from being the push button thing it is today, and Tony DeRose who was bringing subdivision surfaces to Pixar, Ed Catmull’s invention from his days in Utah, which are now standard everywhere in cg. Tony’s was a viable implementation of something that was Ed Catmull’s thesis project under Ivan Sutherland, the ‘father of Computer Graphics’.

Despite all these brilliant minds it was going to be hard to do. I thought, how can we do something that we can actually achieve? So I started by asking: can we make a story with just one character? Because it’s going to be hard enough making just one successful stylized human character at the time. What could I do with just one? So that’s the task I set myself. Can I think of a story with just has one character in it? And of course that’s not what you usually do – you want conflict, something has to happen.

So I ended up pitching this story of an old man, sort of the opposite end of the spectrum from John Lasseter’s baby in Tin Toy. That was another human character as a baby that at the time was incredibly difficult. And Bill Reeves and everyone else who worked on it was sweating blood just to make it happen, and John himself had to make all kinds of turns and twists to get the show to the screen. But what people remember about it is the acting of Timmy, the baby, which is inspired by John’s nephew. And you’re really watching a baby, a young child behaving and playing and cooing and all those lovely things that as an animator you want to get into.

So I wanted to try the other end of life and say, ‘Well what about an old person in this as a cg puppet?’ And then enjoy animating an old character with all the gesticulation and the timing of an old person. Just from an animation point of view, I thought that’d be interesting.

So, I had an old person, I had one character, and I started riffing on ideas from that. It was really just writing things down, drawing storyboards. In the end, I pitched three ideas. I had one idea which was about an old man who was going up and down in an elevator, playing like a kid in the elevator, which we got to a certain level and then we said no. But I was also inspired by my grandfather, my mother’s father, who used to play solitaire chess – chess against himself. As a kid I never understood how that could work. Because you know what you’re going to do next.

The first version of the story that I pitched was terrible. It was just bad. I had a lot of feeling for the character, I had a lot of feeling for the situation, and the idea of this, the fun you might have of him playing against himself, but the actual progression of the story as a story – it was awful. And I remember pitching that to John, and it was one of the worst pitches I’ve ever given, and what was amazing was that I wasn’t shut down and I was given a second chance.

What was terrible about the pitch? What didn’t work?

Jan Pinkava: It didn’t have a shape to it. It didn’t really have a structure. It was too free-flowing, it didn’t make sense as a story with a beginning, a middle, and an end. I wasn’t really following it properly as a structured story. It was too wishy-washy. There was an old man in the park playing chess against himself, but there was lots of weak fat in it like having him arriving and walking in. It was indulging my imagination of how beautiful it would be when it was finished and how we’d want to watch this character just moving, but it was bad storytelling. It really was.

I remember I crashed and burned completely in the pitch. And I realized then also that I was giving the pitch prematurely. It wasn’t ready. That was the hard lesson everyone should learn: when you’re pitching your show you don’t pitch it in a half-hearted way. You’ve got to be ready with a full pitch. It’s got to stand up on its own. You don’t want to be explaining it to anyone beyond what you’re able to pitch. You don’t want to be making excuses for it. A pitch has to be ready.

Was it just an idea at this point or was there any art or any boards you were showing?

Jan Pinkava: I’d already boarded this version roughly. And we did a rough cut animatic and it was, as I say, just terrible. The feedback I got straight away was, start again. So I did and I really worked that much harder on it. I actually changed the style of the drawing and I really worked it through in detail, and by the time I was ready for the next pitch I had a very worked-out story that was very close to what finally happened, missing some beats and moments and scenes, but really very close to the way we ended up.

And it got the green light. Karen Dufilho came on to produce and we started this very technically difficult, strange idea. Karen and I have been friends and colleagues ever since. It was actually a huge leap of faith for John and the studio to support this guy – me – who’d shown up and done well in commercials. But here was a story idea that’s certainly not an elevator pitch: ‘There’s an old man playing chess with himself in a park.’ That’s not obviously an exciting idea when you just say it. Not one of those stories that “pitches itself.”

But clearly the story had heart, and that must have been one of the things that fit into what Pixar wanted.

Jan Pinkava: I loved the idea that here was an old man on his own, and everything was happening in his imagination, and then you play a little bit with the reality of the story, going with his fantasy, and there’s one shot where both characters are in the shot for a brief moment and break the reality. It’s a little bit surreal. And I loved the idea that he was a character, a person with a really rich internal life, a very imaginative person who went through this little game, which was a fight.

I had a friend at school who was a really good chess player and he was the one who first told me that people who were serious about chess – who play at a high level – they don’t see it as an intellectual, dry, analytical kind of high-brow thing. It’s a fight. Chess is a fight. It really is. So if you look at it the right way, it’s actually a very dramatic thing.

Here’s this old man, but he’s playing, just like a kid, and constructing in his imagination a fight between two sides of his personality, and you could enjoy watching him becoming these two people and being into the fight and then being clever and faking himself out and doing all kinds of things, which if you stop to think about it don’t make any sense logically, but are part of someone’s imagination. And it’s very playful, like a child.

And at the end of it when you pull out he’s sitting there laughing all by himself, it’s a very lonely scene but he is a very happy man. And maybe he’s a bit mad, but I always said I hope I’m like him when I’m his age. I may be crazy, but I’m happy.

Do you think the film also taps into how feel people feel about their own parents, or grandparents, and can laugh at that kind of behavior because it reminds them of their family members?

Jan Pinkava: I was really moved by how many people had an unexpected response to the film and that it seemed to mean something to them. This was a nice little idea and I loved it, but I didn’t know if other people would like it in the same way. And imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, all these Youtube videos of people recreating the story started popping up, doing shot-for-shot remakes of Geri’s Game with their grandfather or someone in the park. So it clearly struck a chord.

And on the other side, I was amazed how many people told me that little kids, young kids, were into it. I thought it was maybe a bit too clever, you know, with this idea of you have to get into the joke that it’s just one character as two, and maybe that’s a little cerebral. But because it’s a fight and because it’s a straightforward conflict, I guess, again it surprised me at the time how young kids really liked it as well.

There were things about the acting that I remember pitching and feeling like they were really important, but they’re not the sort of things you can easily explain. Like when Geri gets up for the first time and walks slowly as the old man he is, a little hunched over, taking slow careful steps, to the other side of the table, and then he sits down slow and then suddenly he moves like lightening and goes, ‘Hah!,’ making that first move. I thought that would be funny, but couldn’t really say why.

I mean, that was going to be there from the very beginning, that idea where he takes on this other more aggressive, sharper personality straight away. And the timing is the joke. Suddenly you’re expecting this old man to be an old man, and now he’s suddenly this very cunning guy, and everyone sort of laughs and giggles at that moment. And it’s one of those things that’s just a timing gag. You can’t really explain it. You just do it and it works.

Since this was a film that was meant to illustrate that Pixar could do these human characters, at what point did you know you could pull that off?

Jan Pinkava: The hardest thing was the cloth dynamics. Now it’s a push-button thing in everybody’s animation software, but back then there were relatively few people who could do the math to actually do the cloth simulation. And we knew we had to simulate cloth because you wanted to take that burden from the shoulders of the animator. You don’t want your character animator spending their time tweaking folds in cloth. You just want it to work, like you’re really moving a digital puppet and all the clothes behave properly. So we had to let the machine do that.

Michael Kass worked on the cloth dynamics, and it’s a hard coding and math problem, and it was just not working and not working and not working. One morning we’d come in and look at the overnight renders and there was Geri walking in with mushy stuff on him and suddenly it popped two feet to the left – it was software exploding in random ways. So every morning we’d come in and we’d see some weird cloth disaster; sometimes it looked like oozing concrete, sometimes like Jell-O.

Then finally after just pushing and pushing and pushing and tweaking the parameters of the code and re-writing and re-writing, Michael figured it out, and we suddenly started getting stuff that looked like cloth. We were like, ‘It’s not quite right, it’s still a little bit weird, it’s still a little bit plasticky or wobbly,’ but we were in the ballpark of something that was moving and folding like cloth, and it was really exciting!

And then once we got real cloth-like behavior on this thing we realized what lousy tailors we were. Because we’d completely ignorantly modeled the jacket that Geri’s wearing in this standard crucifix pose of the default character just sticking these tubes of cloth in as the sleeves. And of course that’s not how a real jacket is made. We didn’t think about how we had to tailor this jacket properly. But when it’s all looking like real cloth and he puts his arms down, he’s suddenly got all this extra cloth bunching up under his armpits and it looks stupid. We had this great software that was making cloth look like cloth, and telling us what idiots we were as tailors.

At about that time Steve Jobs came by because he was interested in our work, and wanted to see what was going on. And I remember showing him this test at the moment where we had just figured out the cloth dynamics, I said, ‘Look, we’re really excited, the cloth is working out, but it’s telling us what lousy tailors we are.’ And he looked very thoughtful and said, ‘So your problem is your tailoring, you don’t know how to do the tailoring.’ I said, ‘Yeah, that’s our problem.’ And he said, ‘So what you need is a tailor?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ And he goes, ‘Well, I know a tailor.’ And I said, ‘Oh really, who?’ He said, ‘Giorgio Armani.’

And he was totally sincere, he was ready to call Giorgio Armani, and to this day I’m kicking myself that I didn’t ask Steve Jobs to call Giorgio Armani to tailor Geri’s jacket.

You didn’t do it?!

Jan Pinkava: I didn’t. But he was honestly going to pick up the phone and get Giorgio Armani to teach us how to tailor a jacket. And I thought it was such a great insight into Steve’s character. He would always go for the best he could imagine. Who’s the best tailor in the world? Giorgio Armani. I’ll pick up the phone and call him.

How did the research into subdivision surfaces then come into it, and what did that give the character in your view that hadn’t been done before?

Jan Pinkava: Well, in this short film you’re up close to this one character, and it relies completely on really good acting. It totally depends on enjoying being with him and understanding what he’s thinking and feeling, without dialogue. The digital puppet has to be very expressive so the animators can really act with it. So we knew we had to have more flexibility and more control in the puppet than ever before.

Now, back then we were stitching things together out of NURBs, non-uniform rational b-splines, which are basically squares of rubber. And they were difficult to stitch together in ways that allowed for very expressive characters, especially in hands and faces. So here was a story that’s all about hands and faces, his face and his hands are the main thing and you have to have a very strong performance. Thankfully we were working with Tony DeRose who implemented subdivision services at Pixar. It also didn’t hurt that we had a truly dedicated rigger like Paul Aichele who handcrafted the hundreds of controls that made Geri’s face move so convincingly for the animators. A digital puppet needs good puppet strings.

It was in the middle of making Geri’s Game that everyone could see this new way of making the models, this old new way of making the models, was such a good idea and it immediately went into production on A Bug’s Life. For me it was especially fun because I designed the character, and I got to do a lot of things on the film. It was like making an independent film with so much support. I got to write a story, design the character, sculpt the character, animate a bit on the film, direct it. But of course it’s really the team, everyone making their contribution, and it was a real pleasure to be part of a small and talented team.

I remember working with Pixar sculptor Jerome Ranft who sculpted the clay maquette for Geri’s head, and hands, which we then digitized. And I remember I was noodling him like crazy giving him all kinds of notes, ‘a bit more like this, a bit more like that’, and frankly becoming a bit obnoxious, and then I learned how smart he was from his experience in the business; there came a point when he just handed me the tool and said, ‘You do it.’ No irritation, just a knowing smile.

It was a great way to tell me I was being a lousy director, but also he knew it was a constructive way of moving forward because he knew I was getting into the persnickety detail because I’m a little bit of a sculptor myself – I love sculpture, I’m an amateur sculptor – and I would be better at just doing it than saying it. So I was able to do a bit of work on the sculpture with Jerome to rough it in and directly tweak it rather than noodle him to death with my inept notes.

By the way, once again, the look of the character I completely ripped off from Jiří Trnka. The way he’s proportioned, his nose, his chin, the way his head works, the way the eyes sit in the face, all that absolutely owes a debt to the stylizations of Trnka. All I did was say, ‘What would Trnka do?’ I did a bunch of physical maquettes of different versions of the design before settling on that one, which were just made in wet clay. Jerome took the time to fire that wet clay – solid lumps of wet clay, which would have crumbled to dust as soon as they dried out – very, very slowly in his kiln. And they ended up at the Pixar exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in New York years later among all the other artwork that came from Pixar in that show.

Do you recall how long the production time was for Geri’s Game and what sort of team was on it?

Jan Pinkava: It was like a lot of short films and studios, done with a part-time team, apart from the core research group. The whole project took about a year, which at the time seemed long to me. It was that long because of the R&D, all of the cloth and the surfaces. And I think that we had fifteen animators come through the show. That was one of the challenges for me as a director to try and keep it consistent. It’s a three-and-a-half minute short film, with one character who’s supposed to be the same character even if it’s two different personalities. And some of the animators just came in and did one shot and left.

Pete Docter did a couple of shots because he was just interested; he did a moment at the end where the loser Geri has his little, ‘Pfft, what just happened?’ moment.

Just going back to the production of it, everyone was so busy in the studio making A Bug’s Life that our small crew doing Geri’s Game was pretty much left alone. But also I think there was a big bit of trust there. I remember one particular review with John, and I only saw him a handful of times in the whole thing, and it was he who came up with the beat in the story where after Geri fakes his heart attack, when he comes up again, the bad Geri makes that gesture – you okay? – and the other one goes – yeah I’m fine, I’m fine. That was John’s idea. A lovely little human moment. I remember him acting it out, and I immediately thought of course, that’s great. It gives you a feeling of the character, it’s a lovely idea. And that was an example of bringing in ideas wherever they come from to make it better. Everyone was pitching in improving it, making it better. It was just a great experience. I learned so much.

Geri’s Game went on to win the Oscar for best animated short, but what do you remember about the immediate reaction to the film?

Jan Pinkava: Well, we had a qualifying run for the Academy Awards in L.A. and we had a nice party with all that, which was fantastic. And I remember at the time Aleksandr Petrov had just come out with The Mermaid, a beautifully painted oil painting short film, which blew me away. I was just astonished by the artistry of that. And I was sure he’d win the Oscar. So it was sort of disappointing at the time, it’s like, ‘Ah damn, we had to come out this year when this other film’s up.’

But to get all the support from the studio to make Geri’s Game and to be able to bring it to the screen and to have it get all that wide distribution as the short in front of Pixar’s second feature film, that was amazing. I believe in Europe it didn’t get theatrical distribution with A Bug’s Life, it was only in North America. Nevertheless, it’s on the DVD, so suddenly to have this little film be everywhere was amazing. And it did artistically, theatrically, what the purpose of Pixar’s short films was, what the old shorts in Disney’s day did – to give the audience more entertainment – to be your overture, the little thing that gets you in the mood, the warm-up act for the big feature.

Clearly the tradition continued and continues today at Pixar, and Disney’s doing them as well, as are some of the other animation studios. What do you feel about that history of shorts and whether it should continue, and also what you brought into Google in terms of that short filmmaking experience?

Jan Pinkava: First of all, I think that it’s just a wonderful thing, a really good idea. Obviously it’s a cost to the studio, making short films. Now the question is whether a studio that makes short films can justify that cost and the answer to that depends on whether you take a long-term or a short-term view. If you really take a long-term view and you’re trying to build an audience and you’re really trying to tell an audience we care about you and we want to bring you good work, I think making short films that play before the feature is the right thing to do. Because it pays off in the end just on a cold hard business level. You’re showing the audience you care and you’re giving them more than they paid for. You’re saying we are interested in entertaining you.

And quite apart from that, it’s the means by which a studio that’s trying to be in here for the long run has a way of bringing up new talent, giving new directors an opportunity, and in a technical medium like computer graphics it’s a way of figuring out stuff that you just have to figure out. Because not every major production that you’re involved in is going to push on the things you need to push on to make them happen, technically. So there are all these good reasons on paper why it works, but more than anything, that good will and just giving the audiences more is so important.

What was your Oscars experience like?

Jan Pinkava: Oh, it was such a great thing. I remember being up on the stage with the countdown and it’s a short film, it’s one of the categories that people go off and make a cup of tea and they play you off really quickly. And of course I was nervous and I remember forgetting the name of our lead TD, Dave Haumann, and I was stuck on his name for some very long seconds and then our crew from the balcony shouted the name out and everyone in the theater laughed. It was sweet.

The shorts awards that year were given by Matt Damon and Ben Affleck who just burst out onto the scene with Good Will Hunting. And what was lovely was that they actually bothered to watch – they cared to watch all the short films. And when they were reading out the names of the nominees on stage, the way they said Geri’s Game it was obvious they were rooting for it. It was such a nice gesture.

And so that was a pleasure to receive the little gold man from their hands. And then when I got off stage, Robin Williams was there waiting for them because he’d just won the Oscar for Good Will Hunting, and so we were butting Oscar heads and having a good laugh. I remember having no idea what I was doing and what it meant, because an Oscar is such a symbol of success to so many people in the world.

When we went back to the studio we had an Oscar loan-out program where everyone in the crew got to take it home and share it with their families, because they certainly earned it. I think that’s important, especially in animation, which is all about so many people working together.