A Guide To Pioneering Women In Animation Who Helped Develop The Art Form

In honor of Women’s History Month, we’re highlighting just a few of the trailblazing women who made important contributions during the Golden Age of Animation.

Although it was common practice in Hollywood studios of the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s to hire women to work in the Ink & Paint department – an important role that required meticulously tracing the animators’ drawings onto cels and painting the reverse side – it isn’t often discussed how many women bucked this trend, either by making their own films or rising through the ranks of the studio system.

Women have been working in animation since the earliest days of the medium. Helena Smith Dayton was one of the first artists to experiment with clay animation in the 1910s, and Bessie Mae Kelley was directing her own hand-drawn animated shorts in the early 1920s (unfortunately, Dayton’s films are presumed lost and Kelley’s films are not available online).

The great German animator Lotte Reiniger directed the earliest surviving animated feature The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926), a silent fantasy epic told through silhouette animation, a technique Reiniger invented. Reiniger made the film almost entirely by herself, manipulating paper cutouts frame by frame and photographing her creations on multiple planes of glass to create a layered effect. Reiniger directed over 40 animated films throughout her career, and her beautifully ornate work looks as fresh today as it did in 1926.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

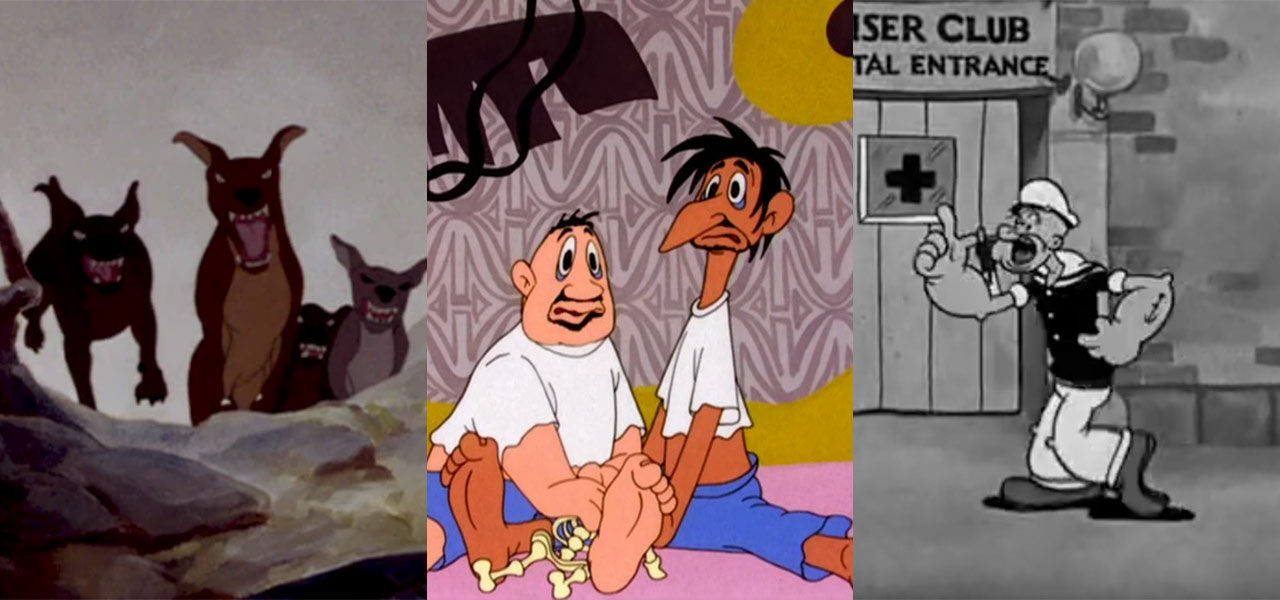

Possibly the first American female studio animator was Lillian Friedman, who worked on the Betty Boop and Popeye cartoons at the legendary Max Fleischer studio in the 1930s. She was hired as an inker, but animator James “Shamus” Culhane saw potential in her work and had her promoted to be his assistant and inbetweener, training her as an animator in secret. Nellie Sanborn – head of the Timing Department – let Friedman animate a Betty Boop test and showed it to the Fleischers “without telling them at first that it was done by a girl inbetweener.” They were impressed, and she was promoted to the position of lead animator. Here is the first scene Friedman ever animated, from the Popeye short Can You Take It (1934). Look at the way she animates those hilarious walk cycles… they’re each so distinctive and loaded with off-kilter personality.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

Another candidate for the title of earliest American female studio animator is Laverne Harding, who received her first screen credit on the Walter Lantz short Wolf! Wolf! (1934). She continued to animate at Lantz until 1960, and was one of the top talents at the studio. Her friend Tex Avery tried to recruit her to be part of his original Termite Terrace unit, and although she chose to stay at Lantz, she later animated for Tex on classic shorts like Crazy Mixed-Up Pup (1955) and The Legend of Rockabye Point (1955). In addition to her animation work, she also drew the 1930s comic strip Cynical Susie. Harding was said to be humble and quiet in person, but she let out her craziness through her work. Here’s a wonderfully wacky sequence she animated in Woody the Giant Killer (1947), featuring Harding’s favorite character to draw, Woody Woodpecker.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

Jewish artists Valentina and Zinaida Brumberg were pioneers of the Soviet animation industry. The Brumberg sisters started making animated films in the late 1920s, and they kept directing until the early 1970s, creating works inspired by fairy tales and folk art. Tsar Durandai (1934), which they co-directed with Ivan Ivanov-Vano, was an influence on the artists who later created the stylish UPA cartoons of the 1950s. John Hubley, creative head of the UPA studio, said of the film, “It was so modern and fresh and violated so many of the totems.”

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

The Brumberg Sisters were among the first artists hired at the Moscow studio Soyuzmultfilm, which became the creative center of animation in the USSR. Throughout the Soviet era, dozens of talented women-directed short films and animated features for the studio. Here are just a few:

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

Hermína Týrlová, known as the mother of Czech animation, directed over 60 stop-motion films from the 1920s up through the 1980s. She was particularly fond of injecting life into inanimate objects like handkerchiefs, snowmen, and rubber balls. She managed to continue working even through the German occupation of Czechoslovakia, and made the amazing anti-Nazi short Revolt of the Toys (1946), in which a bunch of toys fight back against a bullying Gestapo.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

In 1935, American animator and MIT graduate Claire Parker patented the pinscreen, a device with 240,000 small metal rods that can be manually pushed in and out of a grid frame by frame in order to create moving forms. She made many pinscreen animated films with her husband Alexandre Alexeieff, including The Nose (1963), which tells the story of a man who loses his nose and it runs off to live its own life (a problem I’m sure we’ve all dealt with).

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

American artist Mary Ellen Bute was one of the first woman experimental filmmakers, creating purely abstract shorts that she called “seeing sound” films. She wrote that the goal of her work was to “bring to the eyes a combination of visual forms unfolding along with the thematic development and rhythmic cadences of music.” More bluntly, a 1936 newspaper article about her work carried the headline, “Music made visible in weird movie.” Here’s a clip from her film Tarantella (1940).

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

Prior to 1942, women who applied for jobs as animators at Disney were sent rejection letters explaining that the studio didn’t hire women for creative positions. In spite of this, Walt Disney was the studio boss of the era most willing to hire women in prominent roles at the studio, including female character designers (Lorna Soderstrom, Fini Rudiger), layout artists (Sylvia Roemer), story artists (Grace Huntington), writers (Dorothy Ann Blank), music editors (Luisa Field), promotional artists (Gyo Fujikawa), camera technicians (Ruthie Tompson), assistant directors (Bee Selck), and lots of assistant animators. Three women were responsible for the storyboards and concept art for the beautiful “Waltz of the Flowers” segment in 1940’s Fantasia: Bianca Majolie (the studio’s first woman story artist), Sylvia Holland (the studio’s first woman story lead), and Ethel Kulsar (one of the studio’s finest character designers and background artists). The painterly look they achieved in this impressionistic sequence remains stunning.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

Mildred Rossi, who later changed her name to Milicent Patrick, had a fascinating career as an animator, model, makeup artist, and designer of legendary movie monsters. While working in the effects department at Disney, she developed the “pastel effect” used in Fantasia, and arguably became Disney’s first woman animator, tackling clouds, abstract forms, and prehistoric creatures. She later worked on special effects for live-action films at Universal Studios, designing the iconic Gill-man in Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954). Following a press tour where she was dubbed “the Beauty Who Created the Beast,” she was abruptly fired and denied screen credit by Bud Westmore (head of Universal’s make-up department), who was jealous of the attention she was getting. You can see Milicent Patrick’s color animation on the devil himself (primarily animated by Bill Tytla) in this shot from Fantasia, the first of many monsters Patrick worked on.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

Disney’s first credited woman animator was the great Retta Scott. She was originally hired in the story department, but her storyboard drawings of the dog fight in Bambi (1942) were so commanding that Walt Disney and director Dave Hand felt she should animate the sequence herself. Scott said she spent weeks developing the hunting dogs into “vicious, snarling, really mean beasts” and estimated that she drew 56,000 dogs for the movie. Her fellow animators were in awe of her skill, with Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston writing in their book The Illusion of Life, “Retta was strong, had boundless energy, and drew powerful animals of all kinds from almost any perspective and in any action. No one could match her ability.”

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

The Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies cartoons are rightly acclaimed for their brilliant comedy, but they don’t get enough credit for their endlessly inventive background art. Bernyce Polifka worked with her husband Eugene Fleury on backgrounds at the studio in the early 1940s, and she was Chuck Jones’ layout artist for a brief period. Her background designs on the Bugs Bunny short Wackiki Wabbit (1943) might be the wildest and most boldly modern layouts of the pre-UPA period.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

No one understood color better than Mary Blair, the genius designer and color stylist of classic Disney films like Cinderella (1950), Alice in Wonderland (1951), and Peter Pan (1953). She was said to be Walt Disney’s favorite artist at the studio – he had several of her paintings hanging up in his own home – and her eye-popping artwork is still a major source of inspiration to animators today. She was a frequent illustrator of Little Golden Books and designed the It’s a Small World ride at Disneyland. Here’s a striking scene Blair designed for The Three Caballeros (1945).

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

The talented Thelma Witmer was a background artist for dozens of Disney shorts and features, including Lady and the Tramp (1955), Sleeping Beauty (1959), and The Jungle Book (1967). The studio even named a paint color after her: Witmer Red. You can see her incredible work in the Disney short Bootle Beetle (1947).

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

Jean Blanchard was an artist at Warner Bros. in the 1940s, working in Robert McKimson’s unit during his best period. Blanchard was well-liked at the studio, writing for the in-house Warner Club News magazine (she filled her column up with funny caricatures of the rest of the staff) and organizing a bowling team for the WB artists (their first match was against the MGM cartoon studio). Here’s a classic scene from the Bugs Bunny short Easter Yeggs (1947), a film Blanchard worked on.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

Joy Batchelor was a major figure in UK animation. She and her husband John Halas founded the animation company Halas and Batchelor in 1940, and together they produced countless entertainment shorts, instructional military films, commercials, arthouse films, tv series, and full-length features. Halas and Batchelor’s most famous film is their George Orwell adaptation Animal Farm (1954), the first British animated feature released to theaters. Batchelor served as co-director, co-producer, co-writer, and character designer on the film.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

Evelyn Lambart, known as the first woman Canadian animator, was nearly deaf from an early age, so she focused her attention on communicating visually through drawings and paintings. She joined the National Film Board of Canada in 1943, collaborating with Norman McLaren on experimental films, and later directed her own paper cutout shorts. The ultra-cool Begone Dull Care (1949), which she and McLaren co-directed, is a masterpiece of abstract animation. The various squiggles and splotches, painted directly onto the filmstrip, pulsate in perfect synchronization with the jazzy score by the Oscar Peterson Trio.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

The UPA studio, which spearheaded the midcentury move towards stylized animation, had many women designers within their ranks, among them Dolores Cannata, Michi Kataoka, Charleen Petersen, Rosemary O’Connor, and Barbara Begg. One of the best artists at the studio was the shy but supernaturally talented Sterling Sturtevant, an in-demand designer of short films and tv commercials. She was responsible for streamlining the design of Mr. Magoo, giving him a bigger head and more appealingly cartoony proportions (she apparently based his look on her husband), and she became the lead designer and layout artist of the Magoo series in 1953. Sturtevant’s layouts in Kangaroo Courting (1954) are dazzling eye candy, and the string bean body of Juliette is a masterful bit of cartooning.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

Vera Ohman was a background artist at MGM in the 1950s, painting gorgeous backdrops for the likes of Tom & Jerry and Droopy. She later worked on several Hanna-Barbera tv series, including Huckleberry Hound, Yogi Bear, and Snagglepuss. Ohman’s backgrounds in the hilarious Tex Avery masterpiece Deputy Droopy (1955) would look right at home in a 1990s episode of Ren & Stimpy.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

Faith Hubley, alongside her husband John, forged a new path for independent animation in the 1950s. After John Hubley was blacklisted and forced to leave UPA, he and Faith created their own company, called Storyboard Studios. The two vowed to make one independent film per year, and their shorts won three Oscars, making Faith the first woman animator to win an Academy Award. Faith continued to direct films after John died in 1977 – one per year – until her own death in 2001. The modern visuals, jazzy soundtracks, and improvisational dialogue in the Hubleys’ films made them distinctive and original. As Faith herself said, “My choice as a working artist is not to play to the marketplace. It’s not because I don’t know how. I’ve chosen another path.” Here’s a scene from the Hubleys’ Oscar-winning anti-war film The Hole (1962).

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

Shirley Silvey, known for her delightfully flat and goofy drawing style, was a major figure in the early days of tv animation. She started her career as an artist at UPA in 1956 and was a character designer and layout artist on Rocky & Bullwinkle, George of the Jungle, and the Cap’n Crunch commercials. She also conceived and pitched her own tv series Space Granny, which was sadly never picked up. Here’s a characteristically silly episode of Super Chicken that Silvey designed in 1967.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

Xenia DeMattia, often credited only as “Xenia,” might hold some kind of record for the amount of Golden Age studios she worked for. She started at the Ub Iwerks studio in 1933, and hopped around to Charles Mintz, MGM, Walter Lantz, Max Fleischer, Disney, and UPA, usually as an assistant animator. She was given her own scenes to animate on the Disney short Paul Bunyan (1958), and she worked as a full-fledged animator in tv and features throughout the ‘60s and ‘70s. She animated the Ghost of Christmas Past in Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol (1962), the first animated Christmas special ever produced for television, and she drew the character on her Christmas cards that year.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

Ruth Kissane started her career at Disney in the 1950s and went on to work on a wide range of projects. She’s most famous for her work with Charlie Brown, having animated for all of the Peanuts specials of the 1960s. Here’s an oft-quoted bit Ruth animated from the holiday classic A Charlie Brown Christmas (1965).

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

The great Czech puppet animator Vlasta Pospíšilová started her career in the late 1950s, working under stop-motion legend Jiří Trnka. Her talent was such that Trnka regularly assigned her the hardest scenes to animate. She started making her own films in the 1970s, directing nearly 50 in all. She said of her work, “It’s like a disease, but I could not live without it. As an animator, you can do anything. You can be a child, a cloud, water, a parrot, or a line, simply anything. That’s who I am – I’m nervous and trouble seems to follow me around all the time. But then I arrive at the studio and suddenly I’m singing, I feel great, I’m confident. It’s an obsession really.” Here’s a spooky scene from her film Maryška and Wolf Castle (1979).

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

Kazuko Nakamura was one of the first woman Japanese animators, starting in 1956 as an inbetweener at Nichido before it was absorbed by the legendary anime studio Toei Doga. Osamu Tezuka – known as the Father of Manga – was impressed by Nakamura’s work, and she was hired on numerous Tezuka productions; she was a key animator on Astro Boy and animation director of the Princess Knight series. She was also the supervising animator of the character Bokko (a pretty Galaxy Patrol Leader who gets turned into a rabbit) in the pilot episode of the 1960s series Wonder Three.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

Another trailblazer in the anime world was Reiko Okuyama, who applied to the animation studio Toei Doga in 1957 because she mistakenly believed that they published children’s books. She was an inbetweener on the watershed early anime feature The White Snake Enchantress (1958), and her skills got her promoted to lead animator position on classic films like Little Prince and the Eight Headed Dragon (1963) and Horus: Prince of the Sun (1968). She was an animation director on 1960s series like Wolf Boy Ken and Rainbow Sentai Robin, and later worked on the Studio Ghibli film Grave of the Fireflies (1988). She was a strong advocate for women’s rights and she helped push the Toei studio to unionize. This fight scene she animated in The Wonderful World of Puss n’ Boots (1969) shows off her expertise in action and cartoon comedy.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

Just about everyone who worked with Tissa David considered her to be an animation genius, and she worked with greats like Richard Williams, Michael Sporn, and John Hubley. Born in Hungary, she moved to the United States in 1955 and – despite barely speaking English – she became an assistant to Betty Boop creator Grim Natwick at UPA. Among her many accomplishments, she was the lead animator of Raggedy Ann in Raggedy Ann & Andy: A Musical Adventure (1977) and she drew Princess Yum-Yum in the unfinished masterpiece The Thief and the Cobbler. Tissa could evoke reams of personality with only a few frames, a skill you can see at work in this Electric Company segment she animated by herself. As Tissa said, “You don’t do many drawings, but you know how to use them.”

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

The first African-American woman I’m aware of to work as a professional animator was the reclusive Brenda Banks. She started her career as an animator for DePatie-Freleng in the early 1970s, working on a pair of Flip Wilson TV specials and Dr. Seuss’ The Hoober-Bloob Highway (1975). She was head animator of the goons in the Ralph Bakshi movie Wizards (1977), and later a character layout artist on The Simpsons and King of the Hill. She was never interviewed, but her peers remembered her as a shy person with immense drawing talent. She would often chuckle at her own work while drawing, and would rush home to watch the Three Stooges on tv. Here’s a scene Banks animated for Daffy Duck’s Quackbusters (1988).

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

The era of theatrical cartoon shorts came to a close in the early 1970s, just as a new group of animation auteurs like Caroline Leaf, Alison de Vere, and Suzan Pitt started gaining attention and winning awards for their deeply personal independent films. Sally Cruikshank’s cult classic shorts blend the anything-goes surrealism of early ’30s Max Fleischer and Van Beuren cartoons with colorful post-’60s psychedelia, creating an aesthetic totally unique to her. Here’s a scene from my favorite of her films, Face Like a Frog (1987), featuring music by Danny Elfman.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

This overview barely scratches the surface of the many women who contributed to the art of animation in its early days, and obviously doesn’t even begin to cover the countless talented women who came later. To close things out, here’s Retta Scott herself drawing an elephant in the behind-the-scenes Disney feature The Reluctant Dragon (1941).

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) March 22, 2023

Thanks Mindy Johnson, Devon Baxter, and Animation Obsessive

Special thanks to:

Mindy Johnson – https://www.mindyjohnsoncreative.com

Devon Baxter – https://www.patreon.com/devonbaxter/posts

Animation Obsessive – https://animationobsessive.substack.com