Six Insights On Montreal’s Lively Indie Animation Scene

Montreal’s Les Sommets du cinéma d’animation is a festival with a sense of fun and a notion of art that extends beyond animated film. At this year’s edition (December 3–8), veteran filmmaker Theodore Ushev’s masterclass ended in a group maypole dance. One competition screening was hosted by a local drag queen. A rapper sat on the jury. Even as festivals go, there was a buzz about the place.

All this reflects the tastes of Marco de Blois, the artistic director, who imprints his effervescent personality on the festival. But Les Sommets also gains in liveliness from being set in Montreal, one of the global hubs of artistic animation. This is, after all, the home of the monolithic National Film Board of Canada (NFB), the publicly funded powerhouse producer of short films.

Inevitably, the NFB’s presence was felt across Les Sommets: its filmmakers were everywhere, and its productions scooped the prize for best Canadian film, as well as the honorable mention in the same category. Yet the NFB, for all its reach, can hardly work with every indie animator in Montreal — especially at a time of upheaval within the organization. (Cartoon Brew will publish a multi-part interview with the NFB’s producers next week.)

While some animators lamented to me that the NFB dominates, even stifles, the city’s indie animation scene, Les Sommets pointed to many ways around it. What follows is an overview of other systems and institutions in Montreal that facilitate the creation of artistic shorts. This isn’t an exhaustive list — merely my impressions of a week spent at the festival.

1. Animation residency at the Cinémathèque québécoise

The Cinémathèque québécoise, which hosts Les Sommets, runs an annual residency around the festival. Half a dozen filmmakers come to develop an animated short over five and a half weeks. Each is given a mentor and other benefits, such as visits to the NFB. The cohort then present their projects at the festival. This year’s were a vividly eclectic bunch, from Boris Labbé’s philosophical video installation to Lora D’Addazio’s zany occult sex drama.

The program is technically open to all, but Marcel Jean, the Cinematheque’s director (and the artistic director of Annecy Festival), stresses that some knowledge of French is preferred. At least two places are reserved for Canadians, with the rest going to international filmmakers.

Those who stay in Montreal to produce their short receive support. “We try to present them to either private co-producers or the NFB,” Jean tells me. He adds that private producers are relatively rare in the city, and cites Unité Centrale, where he has served as a producer, as one example.

2. Pitching contest at Les Sommets

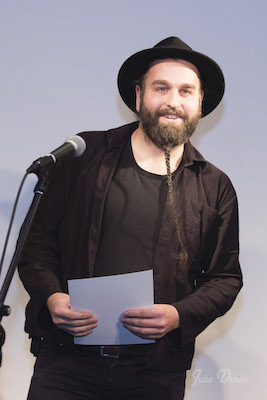

This year saw the festival’s inaugural pitching contest, which Cartoon Brew co-sponsored. Selected filmmakers had ten minutes to pitch a short film in development to a jury (on which I sat). Of the five projects, we picked Max Vannienschoot’s O, a beautifully drawn homage to a friend who committed suicide. Vannienschoot won a package of prizes, including $1,000 CAD from Cartoon Brew, production services, and assistance with his distribution strategy.

By day, Vannienschoot is an animator at Montreal’s Blue Spirit studio. He started developing O on his own, and researched opportunities available to him on advice from friends at the NFB. Eventually, he discovered the pitching contest. “The fact that I was going to present my project really gave shape to my approach, by providing me with a new perspective on production and distribution, and above all by enabling me to meet fantastic people.”

3. Concordia University

Under the banner “the talents of tomorrow,” Les Sommets ran a networking session in which eight Quebecois schools presented their animation courses. The majority are tailored to Montreal’s thriving industry, training students for careers in the city’s vfx, video game, and 2d and 3d animation studios.

Concordia alone prioritizes artistic exploration. The course, at the university’s Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema, welcomes students from all ages and backgrounds — no animation skills required — and helps them produce festival-bound short films (all for far less than the cost of a U.S. degree). Sure enough, Concordia dominated Les Sommets’s student programs with around 15 films in competition.

According to Shira Avni, associate professor of animation at Concordia, graduates end up all over, from the NFB to storyboarding roles in major studios. “We encourage our students to apply to targeted programs [for emerging filmmakers] at the NFB,” she tells me. “We walk them through Canada Council grant processes, we talk to them about artists’ residencies.” She notes that the proportion of international students is growing, and estimates that more than half of all graduates stay in Quebec.

4. Grants

One well-attended event at Les Sommets was Jocelyne Perrier’s talk on funding for short films. Perrier, an experienced producer, reeled off institutions that can provide filmmakers with financial or other support: CALQ, SODEC, MAI, Canada Council for the Arts (whose budgets have grown significantly in recent years), Conseil des Arts de Montréal, and the NFB’s ACIC program, as well as various competitions and artists’ centers.

But there are caveats. Perrier noted that these initiatives are subject to constant change. She also recognized that the institutions she mentioned tend not to have dedicated grants for animation. One filmmaker in the room, Marie-Josée Saint-Pierre, said that the funds are generally biased toward live action, and animation filmmakers are expected to justify their choice of medium — a common grievance among animators applying for grants the world over.

Speaking to me later, Saint-Pierre didn’t mince her words: “Auteur animation isn’t valued here [in Montreal].”

5. Self-production

Filmmakers looking to sidestep the vagaries and constraints of grants and production companies can always go it alone. An exemplar of this approach is Steven Woloshen, who’s been making drawn-on-film animation in the city for 40 years, almost all of it self-financed. Over the decades, he has worked as an insurance salesman, a driver in the feature film industry, and an archivist at the NFB (his current post).

“When you do things for yourself,” said Woloshen in a masterclass at Les Sommets, “it’s easier to finish your film, without any fuss.” He certainly wasn’t the only filmmaker at the festival who works in this way, and the boom in Montreal’s animation and vfx industries has created a wealth of day jobs for artists. At the same time, living costs in the city have skyrocketed, heaping pressure onto self-financed filmmakers.

6. Les Sommets

It almost goes without saying, but the festival itself, which broadly favors indie over industry, is instrumental in bringing all these filmmakers together. Given its proximity to Ottawa, home to one of the world’s major animation festivals, Les Sommets is under pressure to define itself. It does this firstly through the performative aspect I mentioned above, and secondly by restricting its international competition to films that haven’t played at Ottawa (or other festivals in Montreal).

More importantly, the festival remains small-scale and predominantly local — an ideal environment for networking. Finally, it gives exposure to the region’s work through a number of excellent Quebec-Canada panoramas, not to mention the various fringe events described in this article. Les Sommets has been going for 18 years. Long may it continue.

(Image at top: “Pourritude” by Jesse Santerre of Concordia University.)

.png)