Why Audiences Loved Pixar’s First Film ‘Toy Story’

BOOK REVIEW

Toy Story: A Critical Reading

by Tom Kemper

(British Film Institute, 112 pages, pub. date May 2015)

Buy on Amazon

One of the many praiseworthy things about the BFI’s Film Classics series is that it has not shafted animation. This line of slim books has previously covered Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Akira, and Spirited Away. Now, thanks to author Tom Kemper, its coverage of the animation canon has expanded to include Toy Story.

A central theme in Kemper’s analysis is how Toy Story differs from the animated features that preceded it, particularly the Disney canon. As well as the obvious difference in animation technique, Toy Story has a very different tone than most of the animated films that were familiar to audiences at the time. Song-and-dance numbers are out; the nineteenth-century source materials favored by Disney are replaced with more up-to-date reference points such as TV merchandising and the Alien films; and the script uses multi-generational humor more reminiscent of The Simpsons than Beauty and the Beast.

Kemper makes a wide range of comparisons when analyzing the film. He argues that its appropriation of familiar mass culture images gives it a connection to the Pop Art movement, while its approach to physical comedy owes more to Looney Tunes than to prior Disney animation. As is often the case with the BFI Film Classics series, the book is intelligently illustrated. As well as stills from the film itself, Kemper backs up his arguments with paintings by Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein; frames from Chuck Jones, Bob Clampett and Tex Avery cartoons; and even a still from the legendary Twilight Zone episode “Living Doll.”

This last image comes into play when the book discusses the “mutant toys” that inhabit Sid’s house. Even today, when Toy Story has been so widely imitated by other films, these creations stand out. How many animated family comedies have presented us with anything quite as bizarre as that mechanical spider with a one-eyed baby doll head?

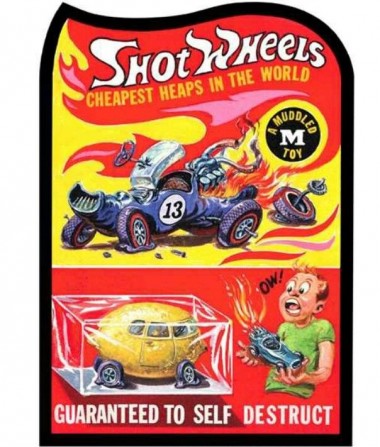

Kemper finds fertile ground when writing about Sid’s weird creations. As well as the obvious nods to The Exorcist and zombie films in the scene featuring the toys’ revenge, Kemper draws parallels with Surrealist art, Bob Clampett’s influential short Porky in Wackyland, and the Wacky Packages trading cards that made their debut in the Sixties. Kemper’s book quotes Wacky Packages co-creator Art Spiegelman as explaining that they were “a young child’s first exposure to subverting adult consumer culture,” while Kemper adds that “if Toy Story celebrates a nostalgic vision of popular consumer toys, the Sid sequences unleash the filmmakers’ nightmarish rendition of this consumer world.”

Kemper finds fertile ground when writing about Sid’s weird creations. As well as the obvious nods to The Exorcist and zombie films in the scene featuring the toys’ revenge, Kemper draws parallels with Surrealist art, Bob Clampett’s influential short Porky in Wackyland, and the Wacky Packages trading cards that made their debut in the Sixties. Kemper’s book quotes Wacky Packages co-creator Art Spiegelman as explaining that they were “a young child’s first exposure to subverting adult consumer culture,” while Kemper adds that “if Toy Story celebrates a nostalgic vision of popular consumer toys, the Sid sequences unleash the filmmakers’ nightmarish rendition of this consumer world.”

This may be an elaborate way of phrasing things, but it is hard to disagree. Toy Story taps into an area of childhood imagination that much of children’s entertainment prefers to overlook. Kemper quotes Toy Story co-scripter Joss Whedon as saying that Sid is the easiest character to relate to because of his imagination, and includes an anecdote about how Andrew Stanton used to mistreat his own toys as a child in much the same way as the film’s villain.

This detail sums up one of the main things that made Toy Story such a success: John Lasseter and his crew were, essentially, kids playing with toys. The kids had trained at CalArts, and their toybox included cutting-edge digital art software, but the basic impulse was the same. And the members of the audience, young and old, shared the same desire to spend time playing with those toys.

SEE ALSO: Toy Story Will Get The Academic Conference Treatment

SEE ALSO: Toy Story Will Get The Academic Conference Treatment

Because of the book’s modest size—it reaches just over a hundred pages—Kemper inevitably neglects a few potentially rewarding topics. He mentions Who Framed Roger Rabbit as a turning point for Disney, but he does not explore just how close a precedent it, or Toy Story, was. Both films have similar senses of humor, along with the same basic premise: familiar childhood characters who are actual actors playing roles. And while the book touches upon the pop culture references found in Aladdin, it does not mention the influence of 1960s pop music on The Jungle Book, or the contemporary setting and visual style of 101 Dalmatians; the modern emphasis of Toy Story’s script, while unusual at the time, was not entirely unique amongst animated features.

Yet Toy Story inspired so many as to be genre-defining, so it is often easy to lose sight of what made the film stand out on its first release twenty years ago. With Toy Story: A Critical Reading, Kemper has given the film the in-depth analysis it deserves.

Order Toy Story: A Critical Reading: