Six Things We Learned From Steve Alpert’s New Tell-All Studio Ghibli Memoir

Having launched on the brand-new streaming service HBO Max, the Studio Ghibli catalogue is now poised to reach new corners of the American market. What better time to release a colorful memoir by the man who helped bring Ghibli to the world in the first place?

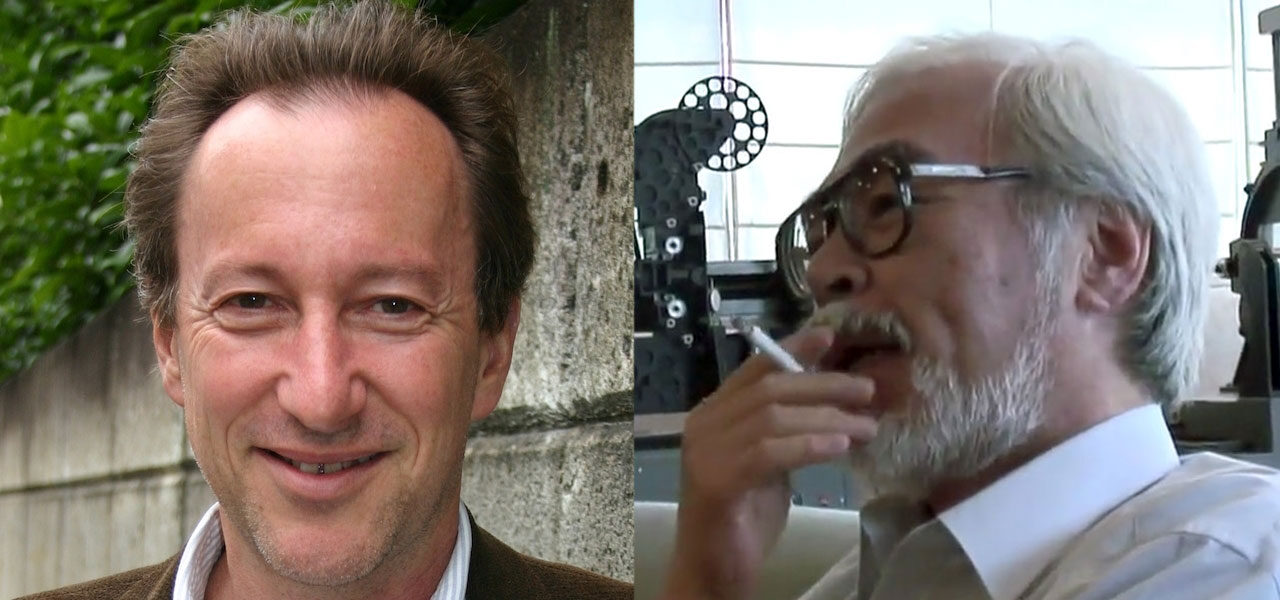

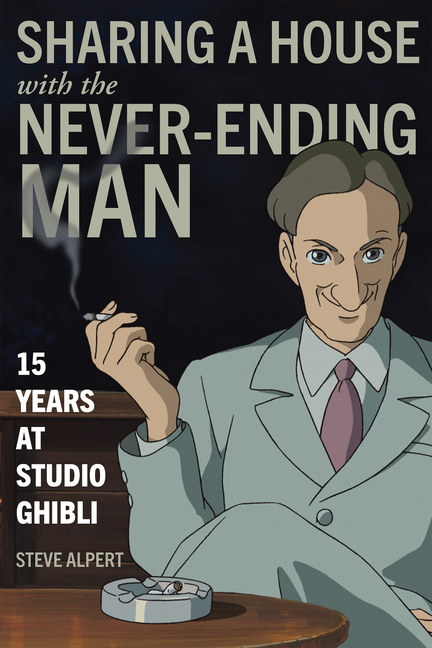

Steve Alpert (pictured top left) led the Japanese studio’s international division between 1996 and 2011, spearheading its efforts to widen its global audience. As Ghibli’s resident foreigner, he was able to observe its culture, and the habits of its mercurial creative leader Hayao Miyazaki (top right), with a certain remove. His massively entertaining account of the period, Sharing a House with the Never-Ending Man: 15 Years at Studio Ghibli, will be published by Stone Bridge Press on June 16.

The book focuses on the first six years of Alpert’s time at Ghibli, detailing the releases of Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away, and the studio’s groundbreaking distribution deal with The Walt Disney Company. The author doesn’t hold back, dishing out new gossip, adding details to stock anecdotes from Ghibli lore, and openly criticizing practices at both Ghibli and Disney.

We’ll publish an interview with Alpert next week; in the meantime, here are six choice anecdotes and revelations from the book’s trove of stories.

Ghibli violated labor laws on Miyazaki’s productions.

Staff would put in “an illegal number of hours” during crunch time. Alpert outlines the studio’s working conditions during his time there: a six-day week, unpaid overtime, a reluctance to take vacations. “And duties such as cleaning the office and serving tea or coffee were mandatory for all female employees (only).”

In the 1990s, anyone could stroll into Ghibli and watch Miyazaki work.

“During the production of Princess Mononoke,” Alpert writes, “I once watched astonished as two local junior high school girls in their school uniforms walked upstairs and interrupted Miyazaki to have their picture taken with him. They made V for victory signs as they posed for the camera. No one objected and they politely left with their mission accomplished.”

Harvey Weinstein made aggressive threats over Princess Mononoke.

Weinstein’s Miramax, then a Disney subsidiary, was the film’s U.S. distributor. At the premiere, Weinstein told Alpert that he wanted to cut the film from 135 to 90 minutes, despite having promised not to do so. When Alpert said that Miyazaki wouldn’t agree, Weinstein flew into a rage: “If you don’t get him to cut the fucking film you will NEVER WORK IN THIS FUCKING INDUSTRY AGAIN! DO YOU FUCKING UNDERSTAND ME?!! NEVER!!” Ghibli resisted and the film was released uncut.

Yet Disney made changes to other Ghibli films without permission.

For example, they released the English-language version of Kiki’s Delivery Service with added music, sound effects, and dialogue, despite a contractual agreement not to make substantial changes. Alpert pointed this out to a dismayed Disney executive, who hadn’t been aware of the changes. He promptly gave the producer in charge of the English version “the kind of verbal lashing that makes grown men cry.”

Miyazaki wasn’t impressed with Fantasia 2000.

On a visit to Disney’s Burbank studio, the director was shown clips from the film, which was then in production. “Asked what he thought of the film so far,” Alpert recalls, “Miyazaki replied simply ‘hidoi … totemo hidoi’ (terrible … really terrible), which I translated as ‘interesting … Mr. Miyazaki finds the animation very unusual and very interesting.’”

Miyazaki refused to meet Martin Scorsese during a trip to New York.

Scorsese invited the director for drinks at his apartment, hoping for the chance “to discuss filmmaking,” but Miyazaki was uninterested. Alpert had to break the news to a desperate press agent. “Can’t you get him to please do this? I don’t want to lose my job,” she entreated. “I think he might just be tired,” replied Alpert.