Little Nemo: A 110-Year-Old Character Sparks Renewed Interest

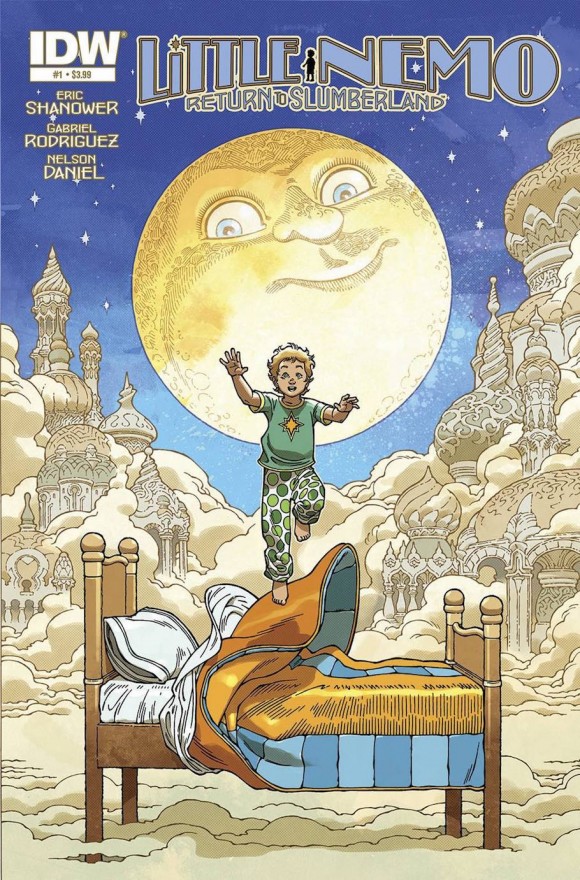

Little Nemo: Return to Slumberland

by Eric Shanower and Gabriel Rodriguez

(IDW Comics, 120 pages, pub. date: June 23, 2015)

Buy: $16.73 on Amazon

Little Nemo: Dream Another Dream

edited by Josh O’Neill, Andrew Carl, and Chris Stevens

(Locust Moon Press, 144 pages, pub. date: Fall 2014)

Buy: $124.99 from Locust Moon Press

Who’d have guessed that Winsor McCay’s 110-year-old comic strip, Little Nemo in Slumberland, would turn out to be one of the hottest properties of the last year?

McCay’s extraordinary draftsmanship and pioneering work in animation has long had admirers. A list of artists and animators who have paid tribute to McCay reads like a who’s who: Chuck Jones, Milton Caniff, Burne Hogarth, Robert Crumb, Rick Veitch, Art Spiegelman, Maurice Sendak, to name just a few. So long as there are dreamers and admirers of great comic art, Little Nemo will have fans, including, fortunately, artists and publishers.

It seems that every few years someone publishes selections or sets of Little Nemo cartoons; Fantagraphics had a multi-volume set starting in 1989, and Sunday Press followed with impressively large volumes in the 2000s. Most recently, the whole of McCay’s masterpiece became available from Taschen in Winsor McCay: The Complete Little Nemo, which has received two 2015 Eisner Award nominations.

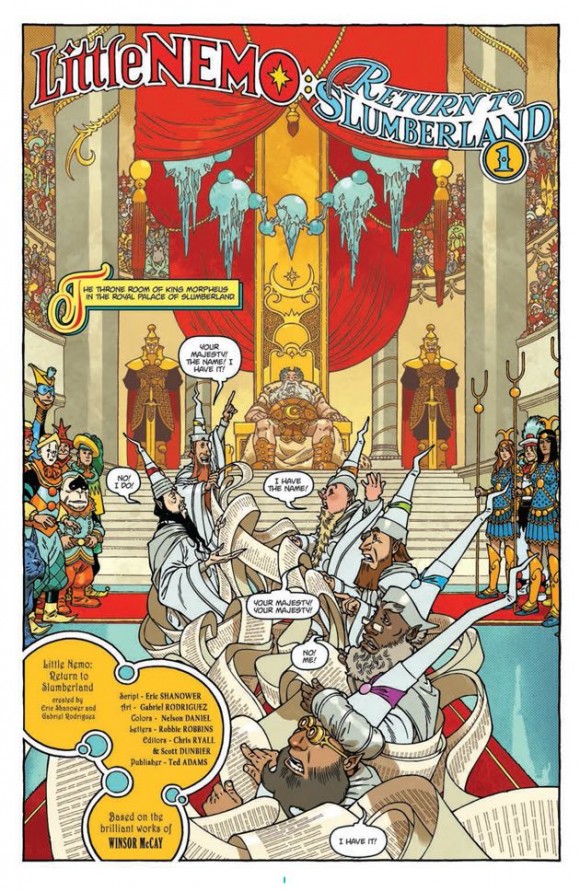

In March, IDW Comics completed their initial four-issue run of Little Nemo: Return to Slumberland by writer Eric Shanower (Adventures in Oz) and artist Gabriel Rodriguez (Locke & Key), with a hardcover omnibus volume to be published in June.

Shanower and Rodriguez have produced a credible, respectful Slumberland, pleasantly reminiscent of McCay’s style, with a few alterations: this is a new Nemo, set years after the original, following a boy named Jimmy Nemo Summerton who is not as eager to be the Princess of Slumberland’s playmate as his predecessor. This allows for contrast between the old-fashioned fantasy of Slumberland and Jimmy’s contemporary sensibilities. McCay’s supporting cast, including Flip, Doctor Pill, and the King of Slumberland remain, but the racial African stereotype “Jungle Imp” character has been tactfully omitted, replaced by a new character called the Frunkus. It’s an enjoyable, child-friendly series, that recently earned three Eisner Award nominations, and IDW could do a lot worse than give the go-ahead for more issues.

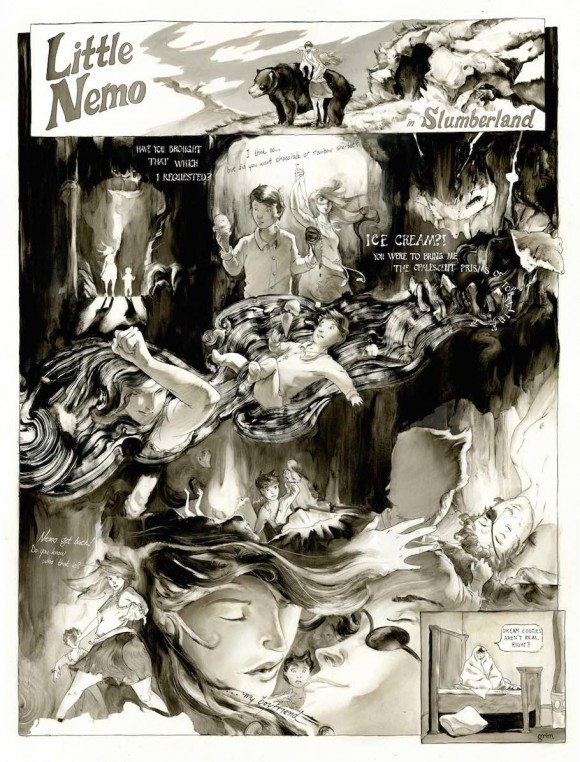

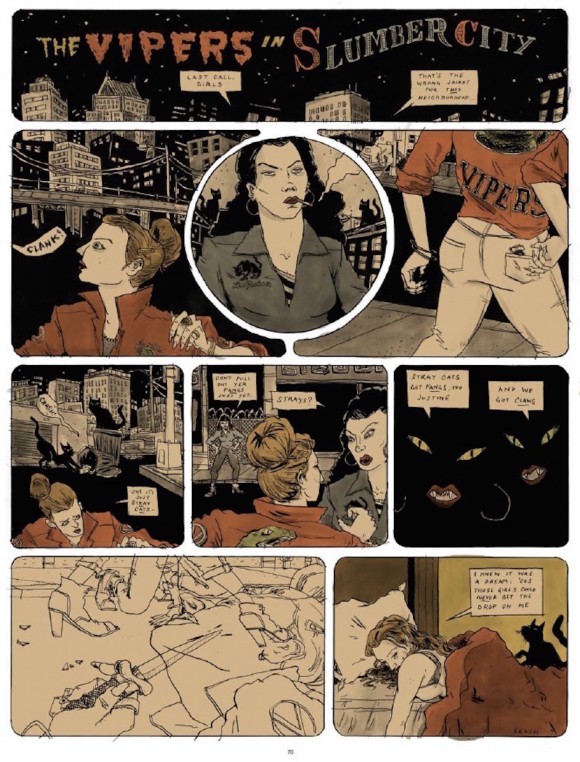

Little Nemo: Dream Another Dream, also nominated for two 2015 Eisner Awards, is another gem: a large format book (16×21 inches) filled with new Little Nemo pages by more than a hundred contemporary comic artists.

With so many creative minds at work, there is considerable room for reinterpretation and pastiche. Nemo becomes a song for artists to riff on—a jazz suite in many movements. Some have produced credible imitations of McCay’s style while others had the sense to let their own strengths shine instead.

Characters and situations cross over: Art Baxter’s depressed stoner Chadley Fowler, from his comic We Three Ghosts, makes an appearance, as does Jill Thompson’s Scary Godmother. Jeremy Bastian, of Cursed Pirate Girl fame, sets his Nemo adventure at sea, while Stephen Bissette takes his Tyrannosaurus rex character Tyrant and recasts him as a Cretaceous-period dreamer. The decades between Nemo and today have brought a lot of new inspiration, and in these Nemo strips are references to Raggedy Ann, Tom Waits, Freddy Krueger, Neil Gaiman, Krazy Kat, and, naturally enough, “Row Row Row Your Boat.”

There are moments of violence and fear, and occasional sexuality—though certainly nothing like Vittorio Giardino’s softcore Nemo-inspired Little Ego comics of the 1980s. Further worthy contributions come from David Petersen, Farel Dalrymple, Yuko Shimizu, Peter Diamond, Maelle Doliveux, and Paul Hoppe. (There’s a complete list of artists involved on the Locust Moon website.)

So how to account for the continuing appeal of Winsor McCay’s work, and Little Nemo in particular? McCay’s draftsmanship is exemplary, but drawing well is only part of the formula for Nemo’s success. Little Nemo is set in two separate recognizable worlds: the mundane one, and the fantasy world of dreams. Though difficult to pull off, dreams are the perfect platform for storytelling: the place where realism and surrealism meet, where allegory, parable, comedy, and tragedy are shuffled and dealt at the storyteller’s command. McCay’s love of late-Victorian decor, fashion, and occasional gadgetry also makes him one of the many grandfathers of steampunk.

It wasn’t all whimsy, either: when Nemo and his friends visit Mars in a 1910 strip, they encounter a sci-fi dystopian nightmare of modern capitalism, where everyone works for one man and even air must be bought.

But wait, not everyone’s done with Nemo. Last year Belgian cartoonist Frank Pé published Little Nemo: Wake Up! but no English edition is currently available. Still to come is Alan Moore’s Big Nemo, with art by Colleen Doran, dealing with the adult life of the little dreamer boy. No release date has been given for Big Nemo as yet, though it has been announced that it will be released through Electricomics.

In case seven Nemo-related Eisner Award nominations wasn’t enough, there is an eighth, in the Best Scholarly/Academic Work category: Wide Awake in Slumberland: Fantasy, Mass Culture, and Modernism in the Art of Winsor McCay, by Katherine Roeder (University Press of Mississippi), which examines McCay’s work in art historical and socioeconomic contexts.

Little Nemo became an essential part of art history long ago, but he’s far from dormant. He is destined to be summoned from his sleep, again and again, by new generations of artists and dreamers.