Interview with John Canemaker about Two Guys Named Joe

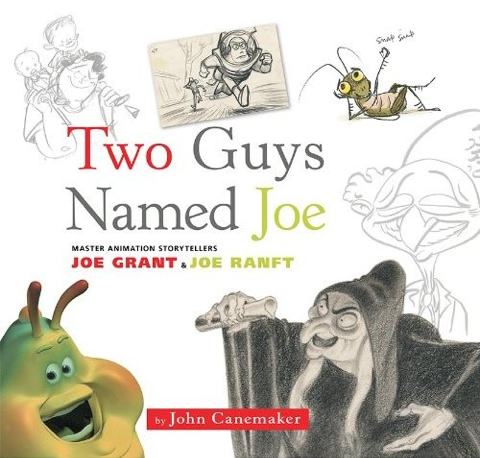

John Canemaker’s eagerly anticipated book, Two Guys Named Joe: Master Animation Storytellers Joe Grant & Joe Ranft, will arrive in stores in early August. The book focuses on the lives and careers of two master animation storytellers who passed away in 2005–Disney veteran Joe Grant and Pixar’s Joe Ranft (who also started his career at Disney). Grant was 97 years old; Ranft was 45–and that’s just the tip of the iceberg in terms of how these men were different. Their combined work has influenced animated features as diverse as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Fantasia, Dumbo, Beauty and the Beast, The Nightmare Before Christmas, Toy Story, and Cars.

As an award-winning author of books such as Winsor McCay – His Life and Art, Felix: The Twisted Tale of the World’s Most Famous Cat and Walt Disney’s Nine Old Men and the Art of Animation, we’ve come to expect nothing less than excellence from John Canemaker’s books and he delivers yet again with Two Guys Named Joe. I conducted an in-depth interview with John via e-mail a couple weeks ago about his new book. Enjoy!

Amid Amidi: Let’s start with basics–why should artists today care about the careers of these two guys named Joe?

John Canemaker: To add to their knowledge of what constitutes excellent benchmarks in animation storytelling, narrative and character development; to find inspiration in knowing the impact that a singular talent can have on an entire film; to discover a creative work ethic that they can (and should) adopt as their own.

Joe Ranft’s mantra was “Trust the Process” and Joe Grant had a sign on his office door reading, “Get to work.” Both artists held the same philosophy regarding the creative process: just do it! Sit down and start in and, if you stick with it, ideas will occur and even flow, visual/verbal connections will be made in concepts, story sketches and scripts. Be open to all ideas and criticisms, make changes, make more changes, and problems will eventually be solved. In their own ways, both Joes were extremely positive and practical in their disciplined approach toward getting beyond the artist’s eternal dilemma: confronting the blank page.

I also think readers of Two Guys Named Joe will find compelling the struggles and challenges each artist confronted, endured and overcame in his personal and professional life.

AA: How did you initially come up with the idea to connect these two artists together?

JC: I knew both Joes for a number of years and interviewed them often for various projects. I considered them friends and enjoyed visiting with them in their respective studios and homes. They were witty, intelligent, superbly gifted, fully alive individuals whose deaths in the same year (2005) deeply saddened me, as it did many around the world.

I got to thinking about how similar they were despite a half-century age gap: their positive can-do approach toward making art, their bottomless creativity, the classic films they worked on, everything from SNOW WHITE to TOY STORY; the difference they made in the art form of character animation; how they each mentored other artists, and more.

Through the art and lives of these two particular guys named Joe, I saw the possibility of an overview of the history of storytelling at Disney and Pixar through a very human story of two artists straddling the 20th and 21st centuries. I ruminated about all this at a lunch in 2007 with V.P./Editorial Director Wendy Lefkon of Disney Global Book Group and she green lit the project before dessert arrived.

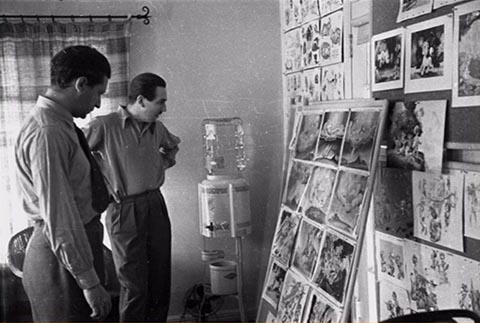

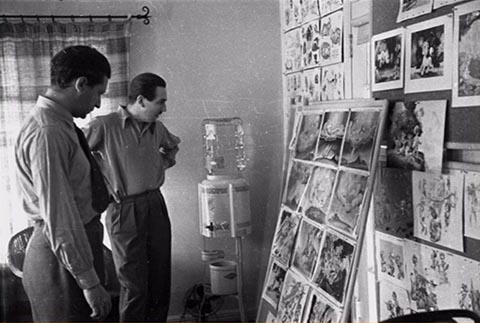

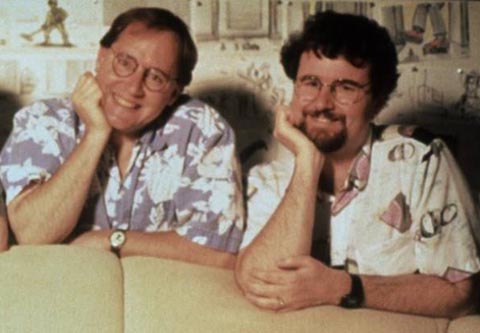

Joe Grant (l.) with Walt Disney (Image from Hans Bacher’s blog)

AA: I want to hear about the practical aspects of writing the book–how long did it take you to research and write it, how was your experience talking to friends and family (especially when dealing with the sensitive nature of Ranft’s tragic death), and what were the unforeseen challenges that you encountered even after having written nine other animation history books?

JC: The book went through five re-writes and shaping (slimming down) over a two year period. Research started during a whirlwind week in LA in July 2007. My partner Joe Kennedy hit the LA Public Library seeking examples of Joe Grant’s 1928-1933 caricatures from the defunct LA Record newspaper, as well as addresses and census records from the period that proved to be a treasure trove of information.

I researched at the Walt Disney Archives, the Disney Animation Research Library (ARL) and the Disney Photo Library. I have worked with these excellent archivists on several projects, so, with advance notice of what I sought in data and visuals, they were ready for me upon arrival and I gathered lots of material quickly. All data and pictures were copied and transferred to disks and sent to me in NYC. Much later in the process, after the text is finally set, I always work directly with a book’s art director to select and place the art and photos within chapters — in this case, the gifted designer Jon Glick.

During that week in LA, I also conducted interviews with Grant family members and his colleagues at the studio, such as Burny Mattinson, Mike Gabriel, Eric and Susan Goldberg, John Musker, Andreas Deja, among others, including Howard E. Green, V.P. of Studio Communications, to whom I dedicated the book.

I dubbed Howard “the patron saint of animation historians,” because for nearly forty years he has helped me and so many of us gain access to Disney artists, information and permissions for our books, articles and lectures. Howard also lavished personal attention on a number of elderly animation masters, such as Frank and Ollie, Ward, Marc and he was especially close to Joe Grant.

In mid-August 2007, I flew to Pixar Studios for a week perusing their archives in search of Joe Ranft visuals, and conducting interviews with his family — his wife Su, brother Jerome Ranft, and his childhood friend John Tschudin — and colleagues, including Brad Bird, Darla Anderson, Bob Peterson, Ed Catmull, Pete Docter, Andrew Stanton, Jonas Rivera, Lee Unkrich. Later, in New York, I did phone interviews with John Lasseter, Jorgen Klubien, Kelly Asbury, Mike Giaimo, Tom Wilhite, Darrell Van Citters, Dean DeBlois, Tony Anselmo, Brenda Chapman and Joe Ranft’s mother Ruth.

Most the interviews were emotional because the deaths of the two Joes were so recent. But all interviewees were forthcoming and generous in detailing their experiences with both men. As might be expected, there was always a bittersweet tinge to even humorous remembrances. My probing was a delicate task. Several Pixar interviewees choked up or came to tears when talking about Joe Ranft. The most unforgettable meeting I had was with Su Ranft, Joe’s widow. After going back and forth about a date to meet in her home, we finally settled on August 16, 2007, not realizing until we got together that it was two years to the day that Joe died.

I first met Su back in the late 1990s when I stayed with her and Joe and their two kids at their Corte Madera home while I was researching my book Paper Dreams. Su is a strong woman and despite the difficulty of reliving so many memories, she was completely honest and candid, and trusted me with incomparable insights into her and Joe’s life together.

The writing process consisted of sifting through the research, including transcripts of interviews conducted by and generously offered to me by fellow animation historians. The writing took about a year. Then came the re-writes and whittling down. Regarding the writing process itself, as someone ruefully said, “Writing is easy. All you do is open a vein.”

Storyboard drawing by Joe Ranft

AA: In animated studio features, the impact of the individual artist isn’t always evident in the finished film but in Ranft’s case, his personal stamp appears throughout Pixar’s output. Has Pixar’s approach to storytelling and characterization changed noticeably since Ranft’s death, and do you think for better or worse? Also, what sort of an impact do you think his unexpected death had in general on the studio?

JC: Joe Ranft’s death obviously deprived the studio of the tactile effect of his presence. This is significant because his mentoring and influence at Pixar had grown into a very personal, one-on-one visiting-country-doctor approach toward every project in the pipeline. He would drop by offices and offer encouragement and advice to his colleagues, who welcomed his help and his just being there for them.

Andrew Stanton described Joe as “almost a guidance counselor” who did “rounds” of the various departments at Pixar. “As a friend and artist,” Stanton told me, “he just cared and wanted to know how you were. It was always a breath of fresh air to get that knock on the door from Joe.” “He’s the kind of guy who would set aside whatever he was doing to help,” Brad Bird said. I believe Joe Ranft’s influence is still pervasive at Pixar; after all he was a prime architect of the studio’s signature narrative style that has connected so well with audiences.

His mentoring of many who are now top Pixar story artists continues to affect the structure and content of the films. I also think the impact of his untimely and tragic death brought Pixar young artists in general to a sharp, indeed shocking, awareness of life’s dark and sad side, the fragility and briefness of our lives, the need to give everything our best shot. I see elements of that awareness of our shared humanity and mortality in WALL-E, UP and TOY STORY 3.

Joe Ranft (r.) with John Lasseter

AA: “Goofy” and “good-natured” are words more frequently used to describe Ranft than “dark” and “troubled,” but the book’s artwork and writing show that there were many sides to him. Looking through the notes in the back of the book, it appears that you had an extensive written correspondence with Ranft through the years, and I’m curious to know how much, if anything, you knew about this other side of him when you first started working on the book?

JC: I was not fully aware of the full range of either his zany humor nor his nightmarish imagination until I spoke with his family and colleagues and saw numerous examples of his personal and professional artworks.

His brother Jerome Ranft clued me in when I interviewed him. He said the laudatory tributes after Joe died were only “half the picture” because “he still hard that dark side he didn’t share with everybody.” Jerome also noted that Joe “did become a fantastic man, but [as a child] he was tough.” Family anecdotes confirmed his personal struggle to transform himself from a young hellion into the giving, caring individual and the creative man he became. “I’ve never seen anyone try to improve himself as much as Joe,” Henry Selick said. How and why he did it is recounted in detail in my book.

AA: In some ways your book can be read as a repudiation of contemporary Disney studio films. The clear parallel you draw between the strength of storytelling in classic Disney films and Pixar’s films leaves Disney feature animation as the odd man out. Was this a point you were consciously trying to make?

JC: It wasn’t a conscious point, but one that could be inferred from the book. The films of both studios speak for themselves. Storytelling strength is a virtue that all animated films should strive for, be they features or shorts, studio-made or independent productions. Perhaps my book will prove to be an inspirational roadmap of sorts toward reaching that goal.

AA: Moving on to Joe Grant, the anomaly about his career is that he is revered almost to the point of hero worship by the younger generation that worked with him at Disney in the Nineties, but remains a controversial (and often disliked) figure by those who worked with him at Disney in the Thirties and Forties. In the book, you talk about how even his close creative partner Dick Huemer refused to speak with him in later years. How do you reconcile these vastly different takes on the same individual?

JC: Basically, there were aspects of his personality that rubbed some people the wrong way and endeared him to others throughout his career. This is gone into in detail in the book. But to briefly answer your question: Joe Grant arrived at the Disney studio in the 1930s as a young man (age 25) full of ambition for both himself and the medium of animation, which he truly loved. He was confident — he had local fame as a caricaturist of note at the LA Weekly newspaper, where Walt Disney discovered him — and energetic, a force to be reckoned with. Walt trusted his taste and judgment and placed him in various influential positions as a designer, story artist, producer, supervisor of a department (Character Model) and writer.

Joe admitted in interviews that he could be arrogant and disdainful toward some co-workers (mostly animators), and over-protective of his crew of concept artists. In turn, there was jealousy on the part of some of his power at the studio, his forceful personality, and his influence on Walt Disney himself. It was a volatile mix.

After he left the studio in 1948 he gradually adopted a placid, Zen-like attitude toward life and his former associates, including Walt. He never uttered publicly an unkind word about any of them. In later years, with a couple of exceptions, former colleagues had a change of heart about him, including Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, who often dined with Joe in later years. And Bill Peet, another supposed “adversary” from the old days, who often phoned Grant to chat.

When Grant returned to Disney after four decades in 1989, the young people at the studio were amazed by the living history in their midst and by his vital creativity — a link to the legendary period they hoped to emulate. He was no longer “management,” but exclusively one of the working artists. However, although he had mellowed in many ways, Joe at age 81 hadn’t changed in terms of his competitive nature or his aggressive selling of his ideas and concepts, or his energy. His outspokenness and persistence made him new “enemies,” especially among the corporate reaches. Read the book for a more detailed dissection of all the above.

One of the things that I’ve always admired about Grant is how he gathered some of the most unique and individual artists at Disney in the late-Thirties and Forties and gave them an opportunity to experiment in a relatively pressure-free environment. Is such a set-up feasible and does it make sense for contemporary studios to replicate? The flip side of that question is how important do you think the character model department truly was at Disney? His unit ceased to exist in later years as the animators assumed more control over the Disney films, and yet the studio continued to turn out features that became classics. Was it an absolute necessity to the success of the studio or should Grant consider himself lucky to have carved out that particular niche within the studio?

Joe Grant great taste in graphic designers included J.P. Miller, Martin Provensen, Mary Blair, Albert Hurter, Kay Nielsen, Aurelius Battaglia, James Bodrero, Helen Nerbovig, Charles Cristadoro, John Walbridge, Campbell Grant, Bill Jones, Duke Russell, Bill Wallett, among others, all of whom he brought into the Character Model Department, which also functioned as a “think tank” affecting story/character research and development.

A separate department may not be economically feasible for many contemporary studios, but all films have viz dev artists who conceptualize and explore the look of a film at the start of a project. Grant’s department wasn’t absolutely necessary to the studio’s success, obviously, but it is an example of how Walt lavished attention on aspects of storytelling during the studio’s great Golden Age, as he did all other areas of the production processes. I do think the style and production value of films such as PINOCCHIO, FANTASIA and DUMBO were enormously enhanced by the diversity of unique artists working under Joe Grant in his Character Model Department,

Interestingly, Provensen told Michael Barrier that Joe Grant “was a remarkable man, and Disney never knew how to use him very well because he wasn’t in the mainstream of the Disney cartoon point f view. He was more European, more . . . interested in the peripheral aspects of drawing . . . and I think he might have done the studio a lot of good if he had had the opportunity to pursue that.”

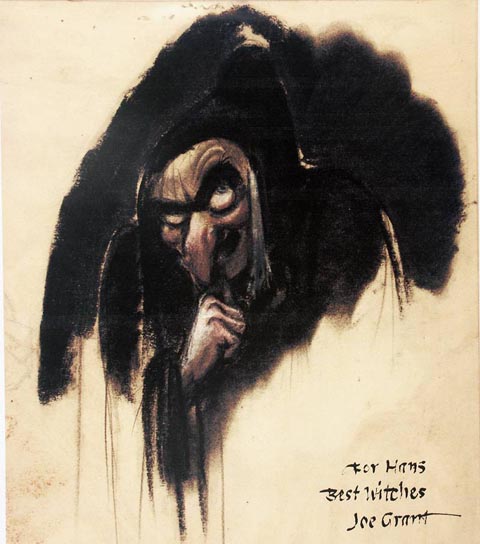

Drawing by Joe Grant (Image from Hans Bacher’s blog)

AA: Though Grant never directly addressed the issue, do you personally believe he wanted to leave Disney on his own accord in the late-1940s or was he forced out of the studio?

JC: I go into detail in Chapter 11 (“Good-bye to Pixieland”) enumerating and speculating about all the reasons why he either left of his own accord or was asked to leave. I feel that Grant could have survived all the studio jealousies, petty backbiting, squabbles, and rumors if he and Walt were on the same page regarding the Disney studio’s future. But they were not.

Walt’s interest in diversifying his product into live-action and eventually television and theme parks was “anathema” to Grant. Joe told me in 1994 he considered animation “the greatest medium in the world.” Indeed, he joined Disney’s in 1933 because he’d fallen in love with the medium itself and its enormous potential at that particular studio.

When Walt made it clear that animation was no longer the focal point of his interests, Grant, the pragmatic survivalist, realized it was time to go. We’ll never know for certain because neither he nor Disney ever went on record about it, but I personally believe he chose to leave.

AA: My favorite part of the book was reading about Joe Grant’s second act at Disney in the 1990s and 2000s and the influence he had on the studio’s output, which was more significant than I’d imagined. In a studio as political and business-oriented as modern Disney, how do you think Grant was able to have such a long stint without any seeming job title or official role at the studio?

JC: Joe Grant delivered. His ideas were of proven value and he was a never-ending source of ideas for gags, situations, personality touches, bits and business — an instinct for enriching the entertainment value of the films. He was also revered and protected by top echelon execs, such as Roy E. Disney and Tom Schumacher, who brought him back to the studio.

It wasn’t easy for him because there were some (directors, producers, marketing types) who didn’t “get” Joe Grant or like his style — his persistence was once compared to that of “running water” which wears stones down. But a greater number of his young creative colleagues “got” him and loved his collaborative, open creativity, his young thinking, and his vast store of knowledge and experience.

AA: Which part of researching Two Guys Named Joe was the most personally interesting to you? Were there any facts or stories that you would have liked to include, but couldn’t fit into the book?

JC: Getting to know the personal side of each Joe and conveying it to readers was most fulfilling to me as a writer. In the people of animation that I write about, I try to find their varied human dimensions, and sincerely try tell their stories with compassion, fairness and truth. This project was fascinating and difficult, but one of the most satisfying I’ve ever had.

I believe I managed to fit in all the major facts and stories I wanted to. In this book, as in my “Nine Old Men” book, I insert a goodly amount of information about the creative process of each Joe. See Joe Grant on “essential questions for filmmakers” on p. 181, and his discussion about the art of caricature in Chapter Four (“Art Director of Myself,” pp. 119-121). See Joe Ranft’s legal pad doodles for NIGHTMARE on pp. 58&59; or his succinct rules for storyboarding (on p. 50), and his blueprint for teaching storyboarding (pp. 83-85).

AA: Has your take on the two Joes changed since you began writing the book?

JC: I do feel I know them better since starting the project and that knowledge has only confirmed the admiration I held for them originally. Personally, I miss them both greatly. So it was a privilege and a joy through this book to really get to know them. I hope readers of Two Guys Named Joe will feel the same way.

Our sincere thanks to John Canemaker for taking time out of his busy schedule to speak with Cartoon Brew about his latest book.

Pre-order Two Guys Named Joe on Amazon for $26.40.