Interview: John Canemaker on Discovering Disney’s Moviemaking Secrets

If John Canemaker had not written his latest book The Lost Notebook: Herman Schultheis & the Secrets of Walt Disney’s Movie Magic, he would still be considered among the very finest chroniclers of the animation art form. But he did write the book—a monumental biography of the unlikeliest of figures—and thus, Canemaker has added to his long list of accomplishments one of the most fascinating and informative volumes ever published about Disney artistry.

It’s a rare feat at this late date in history to write something that makes the reader see the Disney studio of the 1930s in completely new terms. The Lost Notebook does that by upending the animation-centric view of the studio’s films and revealing the inter-departmental teamwork and coordination that made the Disney films possible.

I’ve already praised the book effusively on more than one occasion. Now it’s time to hear from John himself on the process and challenges of creating this unique book.

Los Angeles readers, take heed: John will be lecturing about Schultheis tomorrow evening at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. There are still some tickets left. For more details, see this earlier post.

CARTOON BREW: You first wrote about Herman Schultheis in a 1996 issue of Print magazine (read the original article HERE), and have wanted to write a book about him since the mid-1990s. It seems like such an obvious idea. Why did it take so long to get a book published?

JOHN CANEMAKER: Frankly, no publisher was interested at the time. “Too expensive to produce;” “limited audience;” “too complicated;” “too special;” “Herman who?” were typical reactions. In the mid-1990s, when Howard Lowery, who discovered the books after their half–century of dormancy, first showed me the scrapbooks, we both hoped that a facsimile, annotated version could be published.

That was the purpose behind my writing “Secrets of Disney’s Visual Effects: The Schultheis Notebooks” for the March/April issue of Print, a graphic design magazine. Eighteen years later, the article turned out to be a sort of template for The Lost Notebook. In the meantime, Howard found the perfect archival home for all of Schultheis’ scrapbooks: the Walt Disney Family Museum in San Francisco, which opened in 2009, now owns and preserves the books and showcases the photographic effects scrapbook (which is the subject of The Lost Notebook) in an interactive digital display.

CARTOON BREW: Was Walt Disney’s daughter, Diane Disney Miller, who ran the Disney Family Museum before she passed away last year, involved in the making of this book?

JOHN CANEMAKER: “There is so much interest in the Schultheis notebooks, and you’ve already written about them,” Diane emailed me in October 2010. “Should there be a book,” she asked me, “and, if so, would you be interested in doing it? It doesn’t have to be done NOW, but if you are interested in doing it when you’re schedule permits I can’t think of anyone I’d rather entrust it to.” Needless to say, I wanted to write the book.

Diane and the Disney Family Foundation found a top quality publishing company (Weldon Owen) in San Francisco, who agreed with the format that Diane and I proposed – a profusely illustrated biography of Herman Schultheis, followed by detailed analysis and annotations of the effects notebook itself. I delivered the manuscript to Diane and Weldon Owen’s editors on May 28, 2012 (my birthday) and it was published two years later (May 27, 2014).

Diane was the creative motor who jump-started this project and gave it life, as she did for many projects, including the Walt Disney Concert Hall in LA. It was a great experience working with her – she had the can-do intensity of her father, as I imagine he might have been, and I miss her greatly.

CARTOON BREW: Looking back at your Print article, there was very little information about Schultheis at that time and the main attraction was the notebooks. But in the new book, you expanded the concept to also include a biography of the man behind the notebooks. How, and when, did you make decision to create a biography of Schultheis, in addition to documenting the notebooks.

JOHN CANEMAKER: During the years between the Print article and my starting on the book, tantalizing bits of information about Schutheis began to appear online, especially about his mysterious death in Central America. I love to write biographies. I am fascinated by people—how they choose to live their lives; how luck or fate intervenes in those lives and their reactions to it. When I decide to explore and write about a person, I try to find out who that someone is. And I have always been lucky in unearthing information, be it about Otto Messmer or Vladimir Tytla or Joe Ranft. Herman Schultheis was an empathetic character to me, and I felt that once I started digging into who he was I felt confident that I’d find enough material to write his story. I took a chance that there would be a definite story arc and I was right. During the research phase, things quickly fell into place.

CARTOON BREW: Can you talk about your work from the standpoint of a biographer. Unlike your earlier biographies of people like Winsor McCay, the Nine Old Men, and Mary Blair, Schultheis is a virtual unknown. He worked at Disney for only a couple years and disappeared decades ago in a Central American jungle. Yet you managed to flesh out his life in vivid detail. How challenging was it finding archival materials about Schultheis and what sources did you have to consult to learn about his life?

JOHN CANEMAKER: It was an exciting challenge. Almost every day a discovery was made. But it takes work and persistence. Joe Kennedy, my husband, searched on-line immigration databases, which told us when and how Schultheis arrived in the USA in 1927 and where he came from. Census reports and business records told us where he lived in New York City and his occupations. Ship manifests gave us dates and ship’s names for the trips he took. Knowing he was from Aachen, Germany, we guessed correctly that Herman went to the technical university in town. Joe speaks German and communicated with the university archivists, who provided Schultheis’ school records and information on his family.

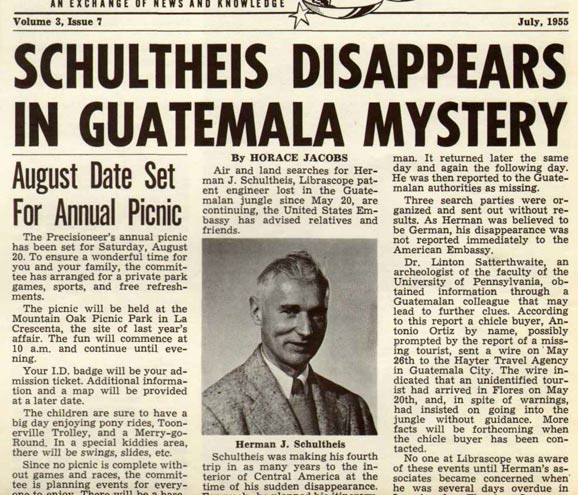

The company newspaper of Librascope, the last place of Schultheis’ employment, provided several articles about his work there and his shocking disappearance in the jungles of Tikal in 1955. Carl Sorenson, Librasope’s archivist, led me to interviews with two former employees who worked with Schultheis. We even found Schultheis’ niece and interviewed her.

The animation historians Howard Lowery and Paula Sigman Lowery were extraordinary in their helpfulness and generosity. During the west coast phase of my research, they made copies for me from their personal collection of Schultheis’ letter drafts, personal photos, correspondence, job search plans, and an interview transcript of one of Herman’s Disney co-workers. Based on this material, I also initiated a Freedom of Information request from the FBI, which yielded detailed information about the circumstances of Schultheis’ death along with correspondence between Ethel Schultheis and J. Edgar Hoover.

At the Walt Disney Archives, director Rebecca Cline found a long-ignored box labeled “Schultheis” containing many artworks, photos and Photostats with notations by Herman regarding his contributions to the animation processes at the time, such as “washoff relief cels.” Several are reproduced in the book.

Dave Smith, Walt Disney Archives founder, and Becky Cline corrected factual errors regarding Disney at the manuscript phase. The knowledgeable archivists at the Disney Animation Research Library and the Disney Photo Library gave me total access to imagery. I looked for unusual rarely-seen (if ever) photographs and artwork, most of which are in The Lost Notebook.

Christina Rice, senior librarian at the Los Angeles Public Library, allowed me and Joe access to the 5,000 photos that Schultheis shot of Los Angeles in the late 1930s, a treasure trove that the Lowery’s generously donated to the library. The catalogued photos are now available online as part of the library’s digital image collection.

I guess the strangest example of how the universe often says “yes” and smiles on the book researcher was when we visited the house that Herman and Ethel Schultheis built. It is located on a steep Los Feliz hillside near Hyperion Avenue and as we parked our car across the street, the current owner came out to suggest we avoid a ticket by parking in front of her house. When we mentioned Schultheis, she recognized the name and invited us inside for a tour of the small residence, describing how it looked when she bought it from Ethel Schultheis’ estate. She also gave me the name of a former neighbor and friend to the widow Schultheis. We tracked him down and he gave me a very informative interview. From Ethel’s will and estate reports we also located her caretaker, who was living in a senior residence. All basic authorial detective work, but every exciting!

CARTOON BREW: Let’s talk more about Schultheis’s notebooks because a lot of people still don’t know the story. Can you give a brief explanation of what these notebooks are and their historical significance to the animation community.

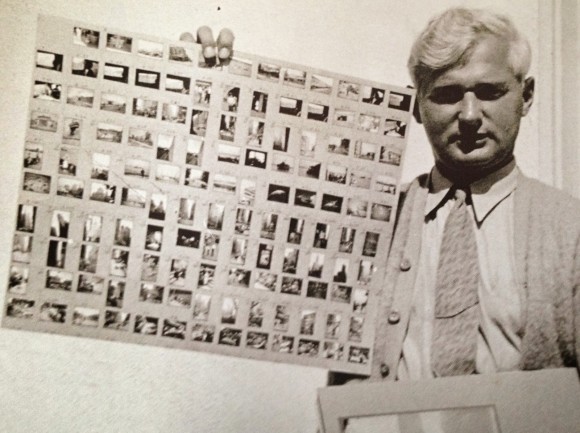

JOHN CANEMAKER: Herman Schultheis (1900-1955) was a man of many gifts: a musician, engineer, avid traveler to exotic ports of call, a gifted photographer, and an obsessive compiler of informational scrapbooks of his many trips and accomplishments. He was ambitious, knowledgeable about so many things, and he wanted to become a power in the movie industry. But that was not to be for several reasons that I go into in detail in the book.

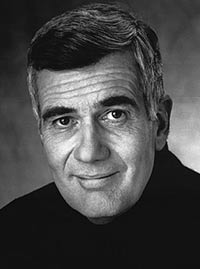

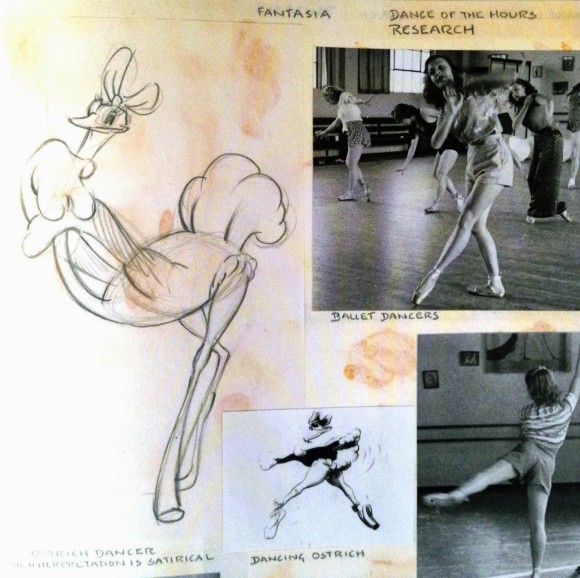

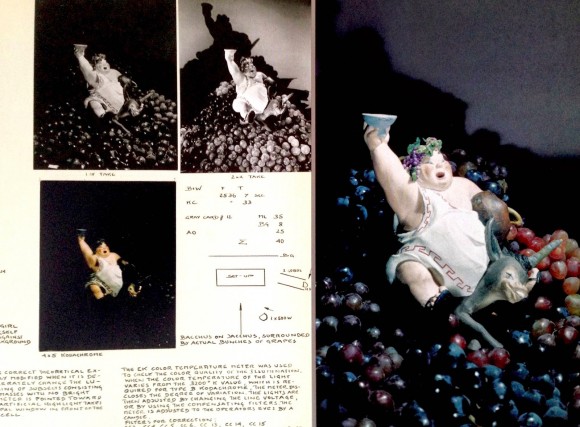

During Schultheis’ brief employment at the Disney studio (1938-1940) in the Special Process Lab and special effects area, he was fascinated by the work he observed and participated in. Realizing he was an eyewitness to something important–the making of fantasy films now recognized as classics during a “Golden Age” at Disney—Schultheis seized a great and unique opportunity to document the aspects in how some of the greatest of animated features, including Pinocchio, Fantasia, Dumbo and Bambi, were made.

His Disney scrapbooks are each incredibly detailed in photos, drawings, charts and notations (sometimes even musical notes). They reveal, for the first time, how many vivid photographic special effects were made; how the coordination of many departments at Disney overlapped; how the improvised, innovative solutions to creative problems were solved, in order to bring beauty, new visual excitement and the highest of entertainment production values to the screen. It also is a rare historical record of the inventive and often simple equipment that was thrown together by effects crews during the analog era, and the constant striving for perfection that should prove inspiring (and perhaps humbling) for today’s computer artists. I have called the Schultheis notebooks the Rosetta Stone of animation, in that they inform us by completing our knowledge regarding how these great and unique film works were made.

CARTOON BREW: For you personally, what are the most surprising technical discoveries in Schultheis’ notebooks? For example, was there anything you read in there that made you go, ‘Wow, I never thought they’d achieved that effect using such a technique.’? Relatedly, have the notebooks made you look at films like Fantasia and Pinocchio differently?

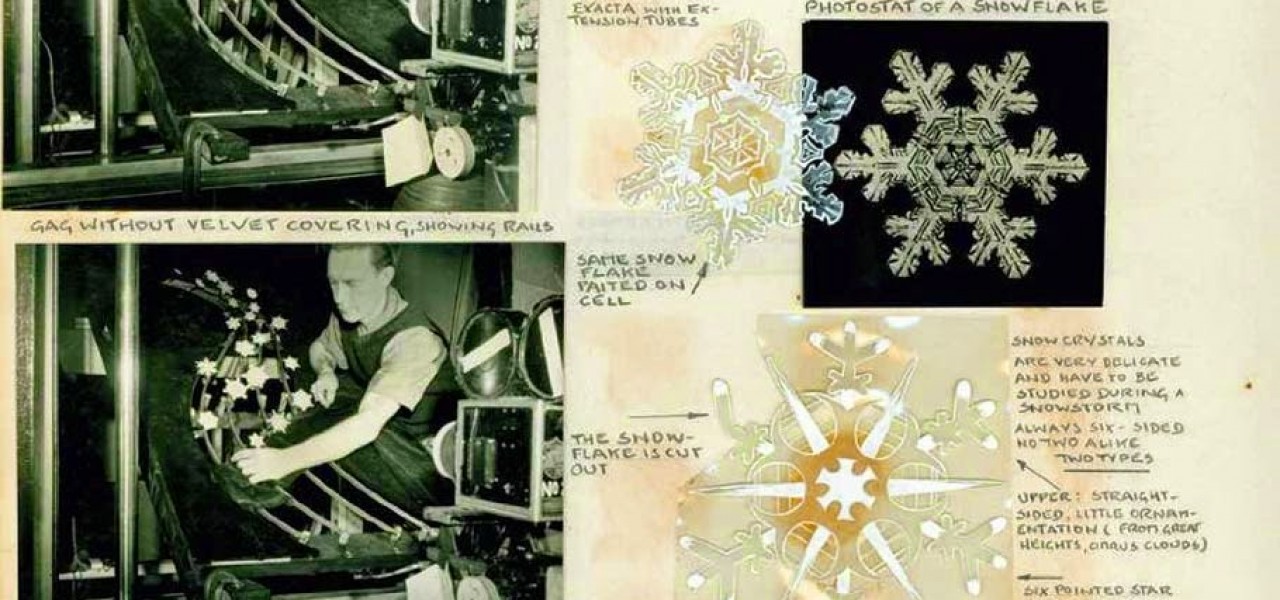

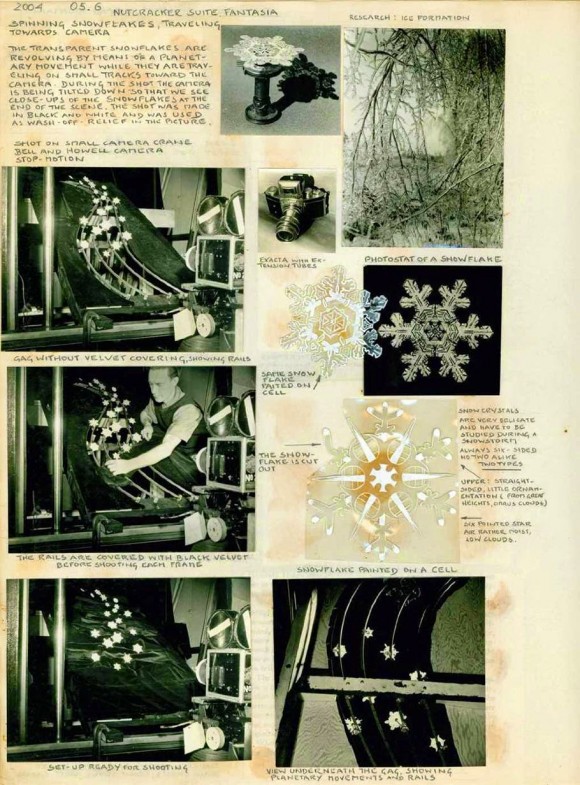

JOHN CANEMAKER: Several pages in the notebooks held an “Oh wow!” factor for me. The mechanical stop-motion means for creating the delicate snowflake ballet finale of Fantasia’s “Nutcracker Suite” using Lionel train tracks (!) was a stunning discovery. Who-da thunk it?

Also, the ingenious use of water to make “volcanic smoke” for the “Rite of Spring”—by pouring paint into a fish tank to Stravinsky’s music. Schultheis’ detailed explanations on each page integrating photos, diagrams and words (and sometimes music staffs) about how the effects were accomplished never ceases to fascinate me.

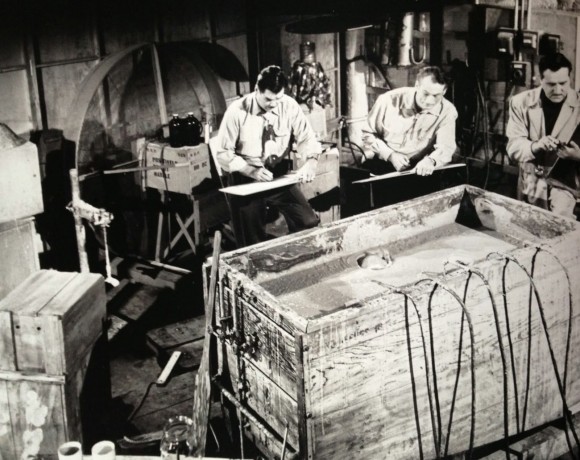

The famous time-consuming and expensive camera truck into Pinocchio’s village as children leave for school is fully revealed by Schultheis. He includes in his notebook the scene’s pencil test stills, layouts, and photos of the horizontal “universal” multiplane camera dolly. He even shows the truck delivering the multiple panes of glass containing the painted overlays and background! Talk about an eyewitness to film history!

It was fascinating to discover that so many effects set-ups were jury-rigged, such as the horizontal universal multiplane camera, and the rotating circular multiplane glass disks for the tracking shot of the cosmos and galaxies in the opening sequence of the “Rite of Spring.”

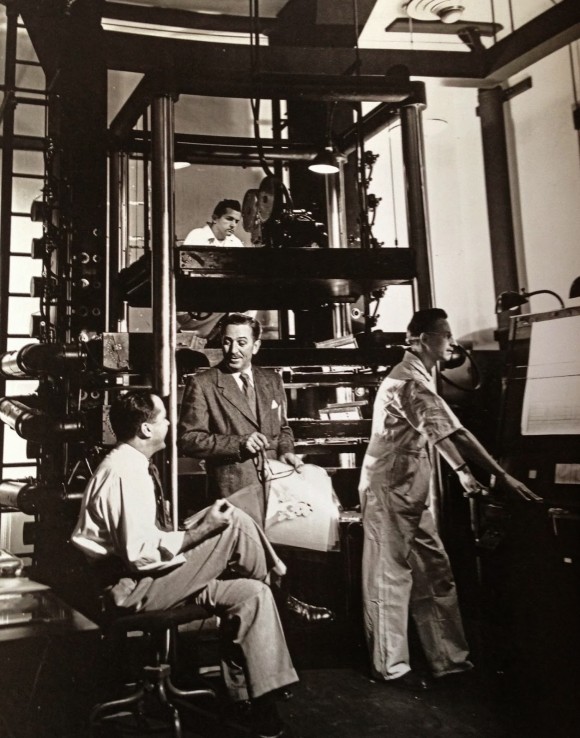

I was also surprised (and delighted) to learn that for The Reluctant Dragon most of the interior locations purporting to be departments within the Disney studio in 1940 were actually constructed on a sound stage. Schultheis was the film’s unit photographer and he devotes twenty pages of photos and notes detailing every aspect of the live-action/animated production, a faux-documentary about how the Disney studio made animated films at that time.

Knowing the back story regarding the imagery in Fantasia and Pinocchio has only made me appreciate all the more the hard work and ingenious teamwork required by the various production departments to bring such consummate and pioneering animation artistry to the screen.

CARTOON BREW: The Lost Notebook, perhaps more than any book that has been written about Disney, upends the animation-centric view of the studio’s films and synthesizes the inter-departmental teamwork and coordination that made the Disney films possible. This is a question I ask with hesitation since I’m currently working on a biography of animator Ward Kimball, but do you think that historians have missed out on the bigger picture of what made the Disney studio special by focusing so heavily on the animation as opposed to a more holistic view of the process? Or is it ultimately all about the animation anyway?

JOHN CANEMAKER: For years, studio publicists focused the public’s attention on the animators. They were the showy part of the process—who isn’t fascinated when animators flip their drawings and Mickey Mouse comes alive and emotes. The Nine Old Men, for example, became a symbolic image of “how films were made” at Disney. The general public didn’t know (and thus didn’t care) about any of the other, often complex processes of “making them move” on the screen.

I have produced and directed animated films and have an intimate knowledge of the varied parts of the animation production process. I felt as a writer that each of those processes were worthy of an exploration of particulars.

But to put it all into one tome would be unwieldy. Maybe someone will do it someday. To appreciate the Disney art form, I believe it is useful to go into detailed explorations of animation’s discrete parts, as I have attempted to do in my books on the history of Disney storyboarding and story artists (Paper Dreams; Two Guys Named Joe), concept art and artists (Before the Animation Begins), or a particular group of animators (Walt Disney’s Nine Old Men & the Art of Animation).

Everyone has a story to tell. I often think how wonderful it would be if we knew details about the lives and talents of anonymous artists, artisans and craftspeople, perhaps those who built Chartres Cathedral or the pyramids or the Palace of Versailles. I think it would be fascinating.

CARTOON BREW: You’ve seemingly researched every aspect of Disney’s visual artistry—story artists, animators, concept artists, and now photographic processes and effects. What, if any, parts of Disney history do you feel have been underserved and deserve further exploration?

JOHN CANEMAKER: How about Great Inbetweeners I Have Known. Animation historian/writer Charles Solomon and I once joked about co-writing In Search of Hanna and Barbara: The Lost Ink-and-Paint Girls. Seriously, there are still plenty of subjects for the intrepid animation writer/historian to explore. I understand there is an Ink-and-Paint Department book in the planning stages. And a book on the history and construction of both the Hyperion and Burbank studios.

And Didier Ghez is working on the first of a series of books that will further investigate Disney conceptual artists, and promises to add new information to the subject. There are specific layout and background Disney artists that, I think, could also be interesting book subjects. I personally would love to do separate analytical/biographical studies of the life and work of the great animators Vladimir Tytla and Frank Thomas.

Outside of Disney, there is also, of course, a wide world of animation, both historical and current, that writers, researchers and publishers should consider as subject matter. Animation history and the artists who were part of it is a rich subject for exploration, and history in our digital age is being made every day.