Why Giannalberto Bendazzi’s Animation History Book Must Be Published

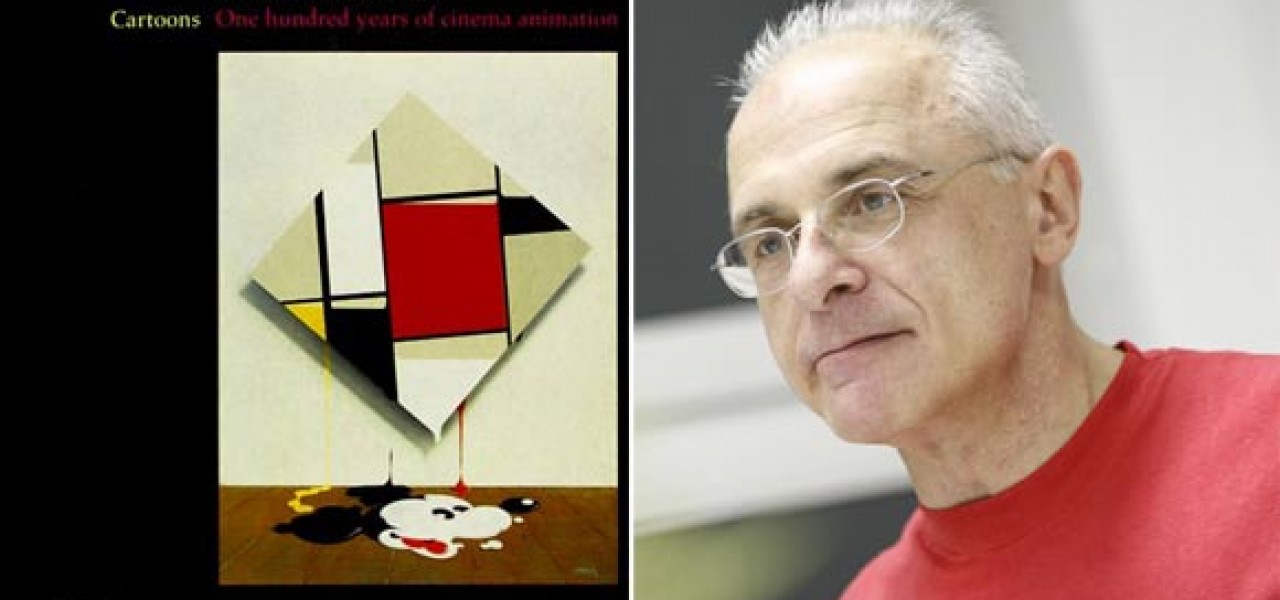

A few months ago, in a round-up of the highly anticipated animation books of 2014, I included Italian historian Giannalberto Bendazzi’s updated version of Cartoons: One Hundred Years of Cinema Animation on the list. For those who don’t know, the original volume, published in the United States in 1994, is the single finest survey of global animation history. It’s an indispensable book that I keep within arm’s reach at all times because nothing else exists like it. Not only is Cartoons more comprehensive than any other single volume about global animation, its writing is a model of eloquence and conciseness that inspires the reader to seek out the films and animators discussed in the book.

For these reasons, I’ve been looking forward to the updated version of the book for quite a few years. It promised to be a magnificent tome—nearly 700,000 words and 2,000 pages in its manuscript form, and thoroughly up-to-date on the massive growth and global expansion that has occurred in animation during the last three decades. The book had been commissioned by John Libbey Publishing, a British publishing house that specializes in film, animation, and media books. As with the earlier edition, Libbey planned a co-publication, in which a U.S. university press would publish the book for American audiences, while Libbey would handle international publishing.

Unfortunately, its publication hit a snag after Libbey tried to sell the book to American publishers. Multiple publishers, among them, Indiana University Press (which published the original edition) and the University of California Press, turned down the book for the reason that it was “too big,” Bendazzi tells me. Unable to find a publishing partner, Libbey sold back the book rights to Bendazzi. That is good news, the author says, because it means that he can now find another publisher. But it’s bad news for those of us who have been waiting for the book for years because it means we will have to wait even longer.

As any animation historian can attest, Bendazzi’s story isn’t unusual. Even as the animation industry is booming, there is noticeably sparse interest in documenting the historical movements and contemporary trajectory of the art form. It is inconceivable that a major volume on film, music, art, or literary history would be turned down on the basis of its length, but for animation that somehow seems completely normal. Mark Lewisohn’s new biography on The Beatles is nearly 1,000 pages—and that’s only part one. Robert Caro’s The Power Broker, a biography of New York City urban planner Robert Moses, is over 1,300 pages—and that’s a book about a single individual. Whereas those books are celebrated for their comprehensiveness, animation histories don’t get any praise for being comprehensive. Publishers believe that the 110-year history of the art form and its thousands of practitioners must be constrained to a neat and tidy length because no one wants a more detailed account.

Except some of us do want the detailed account. We have a sincere interest in learning about all the varied approaches to animated filmmaking, and exploring its limitless expressive means. And we don’t care if it takes a few hundred extra pages to tell that story. If Bendazzi’s new version of Cartoons is anything like the earlier edition—and I have no doubt that it will be—then it is a book that deserves to be printed on paper and given a prized space on the bookshelf of any serious animation fan, artist, and scholar. Let’s hope that some publisher agrees and makes this book a reality. They can contact Bendazzi at GiannalbertoBendazzi.com.