Book Review: ‘Toons in Toyland’

Toons in Toyland: The Story of Cartoon Character Merchandise

by Tim Hollis

(University Press of Mississippi, 306 pages, pub. date March 2015)

Buy: $29.42 on Amazon

Many of us owned lunchboxes emblazoned with cartoon characters when we were children, but few of us ever thought about the politics that went on behind these items, as rival manufacturers battled for the most lucrative licenses. Similarly, few of us ever stopped to consider who ghosted for Charles M. Schulz on illustrated Peanuts tie-ins, or wondered whether or not those crudely moulded carnival prizes were officially authorized.

But, as Tim Hollis’s new book Toons in Toyland: The Story of Cartoon Character Merchandise demonstrates, the history of cartoon merchandise is a fascinating business indeed.

Hollis homes in on the baby boomer era, focusing on products made during the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. Within this timeframe he manages to cover a comprehensive range of merchandise including toys, board games, books, records, foodstuffs, and more.

As well as providing a trip down memory lane for readers who grew up in those eras, Toons in Toyland has plenty to offer a wider audience of animation buffs. For better or worse, merchandising is a key part of the cartoon landscape, and so there is certainly a place for a book that takes a good, long look at the period when animation merchandise was really taking off.

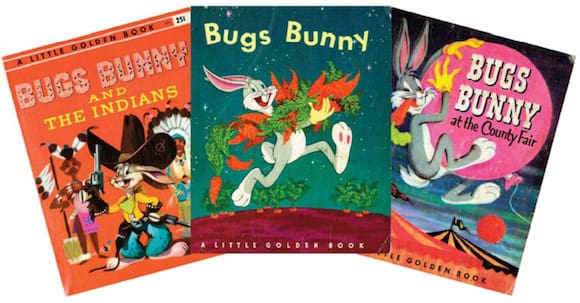

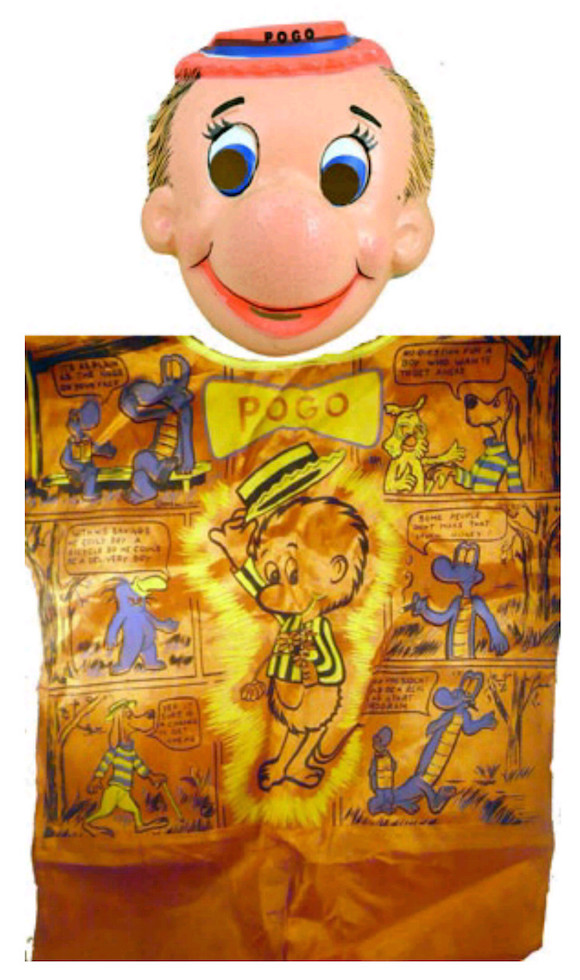

One of the most entertaining features of the book is its exploration of how off-the-mark the merchandise could get. We are treated to the sight of Barney Rubble with his toenails painted green and what appears to be a lily pad on his head, a genuinely unsettling Pogo Possum Halloween costume, and a whole array of bizarrely misshapen Bugs Bunnies.

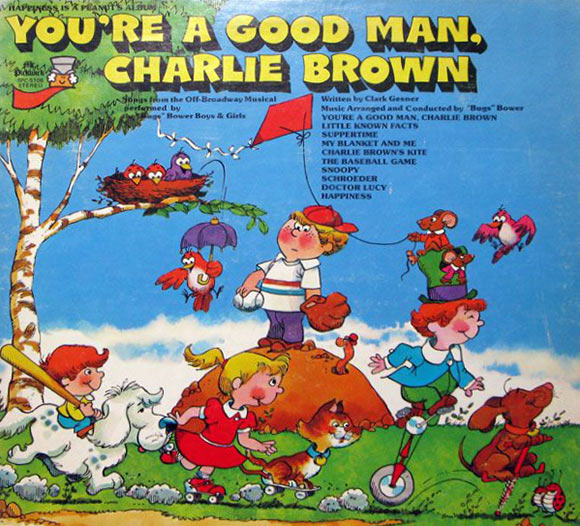

There were sometimes legitimate reasons for these aberrations. The complex copyright status of Popeye’s antagonist Bluto/Brutus led to the character being dubbed “Mean Man” on certain merchandise items, or replaced altogether with a generic bully. Record labels were allowed to release cover versions of Peanuts-derived novelty songs such as “You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown” but were barred from showing the strip’s cast on the sleeves; some of them got around this with original characters that evoked Schulz’s creations (a boy with a baseball bat, a dog in a biplane) without using his designs or even emulating his style.

Meanwhile, early merchandise for Disney’s Winnie the Pooh showed the animated versions of Pooh, Eeyore, and Christopher Robin alongside E.H. Shepard’s interpretations of Piglet and Tigger, since the latter two characters had not yet been given official Disney makeovers.

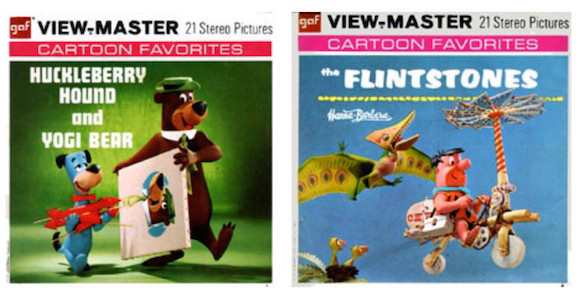

Technological innovations only led to more ways for manufacturers to tarnish beloved characters. Whereas earlier cartoon characters frequently looked a bit odd, the Talking View-Master made characters sound odd: instead of the original voice actors, the likes of Bugs Bunny and Fred Flintstone were obviously played obviously by egregious stand-ins.

In some cases, it is not the execution but the basic concept that leaves you scratching your head. Hollis shows genuine bewilderment at the existence of cartoon character punching-bags that gave children the ability to physically assault Mr. Magoo.

But as fun as it may be to poke fun at the merchandise that got it wrong, it is also worth noting how often the merchandise got it right.

Many of the items featured in the book added interesting new aesthetic interpretations of characters. Sometimes this is most likely accidental—witness the funky abstract stylings of Colgate-Palmolive’s cartoon bubble-bath bottles—but other times it is the work of commercial artists who took their jobs seriously. Carl Barks’s Donald Duck comics and the lushly-illustrated world of Little Golden Books spring to mind, along with a few less obvious examples.

View-Master reels contained 3D scenes of various cartoon characters, often recreated in clay. Lelia Pearson was tasked with translating Road Runner and Charlie Brown into this new medium while Joe Liptak tackled many of the Disney and Hanna-Barbera reels, both of them making many of the same aesthetic considerations as stop-motion animators in crafting their lively and inviting dioramas. It is no exaggeration to say that Liptak’s interpretations of Fred Flintstone and Huckleberry Hound have more energy than the characters’ on-screen selves.

Determined to create more than just a coffee table book, Hollis packs each chapter with details about the intersection between the animation and comic industries, providing insight into the politics that went on behind the scenes. The final chapter moves beyond the baby boomer era and skims over the period from the 1980s to the 21st century. It concludes, appropriately, with the Toy Story franchise—the ultimate realization of the animation-merchandise ouroboros.

Hollis keeps an upbeat tone throughout: even at his most critical of the merchandise, he writes in a tone of fond amusement. But the nostalgia of Toons in Toyland is inevitably laced with melancholy. In its way, the book is a kind of pop culture graveyard, filled with monuments to such long-gone characters as Secret Squirrel, Linus the Lionhearted, and the Shmoo.

This is neatly summed up in a strangely poignant story late in the book involving Yogi Bear Honey Fried Chicken, a restaurant chain founded in 1968, whose eateries were decorated with large fiberglass figures of Yogi and friends. When the restaurant chain finally shut up shop, the characters were dumped at a North Carolina truck stop, where they deteriorated over the years with neglect before finally being discarded, though they remained in plain sight. For some time afterwards, passers-by would pay their respects, with macabre fascination, at this mass grave of decaying Yogis, Boo Boos, and Ranger Smiths.

Order Toons in Toyland on Amazon:

.png)