Book Review: ‘Pulses Of Abstraction: Episodes From A History Of Animation’

Pulses of Abstraction: Episodes from a History of Abstraction by Andrew R. Johnston. University of Minnesota Press.

Andrew R. Johnston’s book will undoubtedly frustrate general readers with its dense academic writing. It’s a shame that Johnston, an associate professor of film and digital media at North Carolina State University, is speaking to a very specific audience, because once you get passed the at-times-dry scientific tone, this is a fascinating and important look at some key voices in abstract animation and how their unique perspectives overlapped with technical innovations to create new visions and trends.

The thrust of Johnston’s goal is to explore “how the trajectory of animation’s continual return to the technical exploration of movement is always modulated by the media ecologies from which the inquiries begin.” The author focuses specifically on animation’s “rapid technological development from the 1950s to the 1970s,” tracing “the mechanical and aesthetic actions that are most prevalent within abstract animation from the time.”

Each chapter focuses on “one specific element of art or moving image technology in order to fully explore its contours of articulation.” For Johnston, those key elements are line, color, interval, projection, and code. A final section then focuses on the re-animation work of American filmmaker Lewis Klahr.

Chapter One studies the use of line in abstract work and specifically how Len Lye explores it through his scratch animation work. For Johnston, “Lye’s films explore animation’s technical nature. That such an engagement takes place through the abstractions and movements of the line exposes this form’s own contradictory simplicity and expressiveness.”

Chapter Two shifts to color and Thomas Wilfred’s pioneering lumia art, “an aesthetic that uses color and projection experiments built through a machine called a Clavilux” (a kind of color organ used to project abstract patterns of colored light on a screen). Johnston argues that the medium of lumia influenced the abstract use of color and “a type of animation constructed not out of frames of film and time separated by intervals that are perceptually effaced during projection, but instead by a seamless flow of projected light whose movements are controlled through the varied intensity of its source in addition to filters and glass that determine its color.”

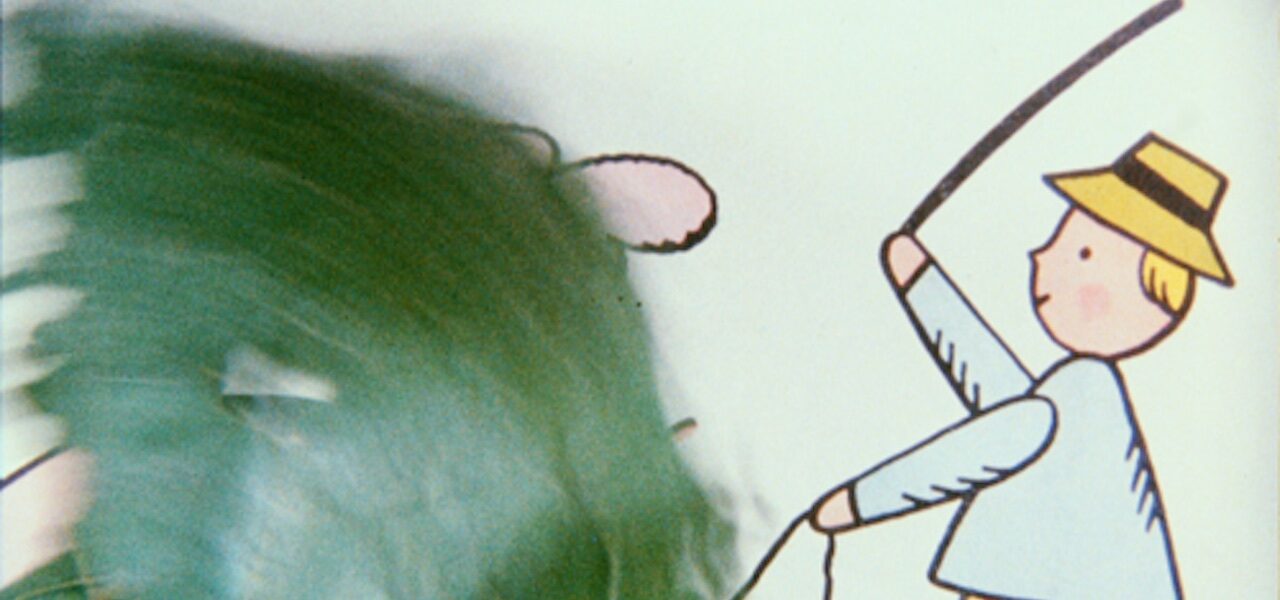

Robert Breer’s use of time (or interval as Johnston deems it) in his collage films is the focus of Chapter Three. Breer’s “collages produce juxtapositions in time as noncontinuous images flicker through barrages of formal plays and combinations at breakneck speeds.” And by manipulating the interval between each frame, Johnston suggests that Breer is liberating the viewer, enabling them “to inhabit new technical modes of time.”

Mary Ellen Bute’s work of the 1950s is explored within the context of projection in Chapter Four. Johnston suggests that Bute’s use of the oscilloscope (a device that visualizes frequencies) served “as a new means of creating abstract animations that would measure and visualize sound inputs.”

Chapter Five explores the work of early computer animation pioneers like John Whitney, Larry Cuba, Lillian Schwartz, and Charles Csuri. As he traces the development of real-time digital filmmaking, Johnston focuses on “how artists, programmers, and engineers wrestled with the problem of time while developing digital graphics systems, working through visions of animation and ideas circulating through scientific and media landscapes of the moment,” and how these technologies “generate[d] new aesthetic and technical modes.”

The final section explores the work of Lewis Klahr, whose films use collage to re-animate the past. Drawing on an assortment of pop culture imagery from the 1950s to the 1970s or so, Klahr uses these images to show the effects of those times on the present, and also to deconstruct the romantic promises linked with so much of that imagery.

It’s impossible to do proper service here to Johnston’s dense, passionate, insightful, and multi-layered study. Pulses of Animation is an important and much-needed analysis of the development of abstract animation, some of its pivotal voices, and their overlap with assorted technological developments of the time that continue to influence animation art today. Like an archaeologist, Johnston digs deep into abstract animation’s recent past and “cast[s] light on lingering shadows whose sources are forgotten.”

Image at top: Robert Breer’s “Fist Fight”