‘Return of the Jedi’ and ‘Roger Rabbit’ VFX Supe Ken Ralston Reflects on the State of the Industry

Visual effects supervisor Ken Ralston has won five Academy Awards – for Return of the Jedi, Cocoon, Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Death Becomes Her, and Forrest Gump. He’s been nominated for three more (Dragonslayer, Back to the Future Part II, and Alice in Wonderland).

Ralston, whose work straddled both the optical and digital visual effects eras at ILM for two decades before he moved to Sony Pictures Imageworks, is tonight being presented with the Lifetime Achievement Award at the 15th Annual VES Awards. Few supervisors have had the opportunity to contribute to as many landmark effects films as he has, let alone those that have utilized such diverse techniques as miniatures, stop-motion, optical compositing, digital compositing and cg, early performance capture, and virtual environments.

Now senior vfx supervisor and creative head at Imageworks, Ralston walks Cartoon Brew through some of his career highlights, the lessons from The Polar Express and other films, what film projects he was involved with that never got off the ground, and what visual effects he’s taken (and not taken) particular note of recently.

Cartoon Brew: As a visual effects supervisor with so much experience, what have you seen that has impressed you lately?

Ken Ralston: You know, that’s a good question. I think things that grab me are ones that surprise me. Ex Machina – I watched that and I loved it. Loved it. And I just thought it was a wonderful use of visual effects.

And before that, several years ago it was Children of Men. I just wasn’t expecting such disciplined and nuanced work. I don’t know why. I didn’t even know what the movie was about. So those kind of surprises are cool. Or The Revenant I thought had some great stuff in it. Even crazy stuff like, well, even Alice Through the Looking Glass – there’ll be things that turn out better than I think it’s going to.

I love working with a crew that will surprise me in such great ways like that so I can be surprised that way too. This last year, there’s several, but I’m just going to pick out The Jungle Book. I thought it was astonishing, the quality of work that they did. It’s hard to say, because you look at all the movies that are up for the Oscars and they’re all great.

And, I don’t mean anything bad about the people working on some of these movies, and their work is always great, but movies about superheroes, I’m sort of brain-dead towards that at this point, so it all feels like I’m watching the same movie sometimes.

Above: In this official Star Wars video, Ralston discusses how he used videomatics to help plan a vfx sequence in Return of the Jedi.

You really worked on some big, big visual effects films, and looking back at films like Roger Rabbit or Forrest Gump, it seemed to feel like they were asking you to do almost the impossible. What is your first reaction when you get asked to do these really challenging effects?

Ken Ralston: Well, my first reaction is – of course I want to do everything possible to do it. I’ll read a script and at first a large percentage of the movie feels impossible at the time. But it keeps you awake. That’s why they’re hiring you. You know, if they want to do the same old schtick on a film then they can go somewhere else. But I just enjoy the challenge of not really knowing exactly how I would pull something off. There were times, a few times on different movies, especially Bob Zemeckis’ movies, where I thought I couldn’t make it work the way they wanted. But that was very rare.

The mirror shot in Contact is one of those classic shots that people still talk about. Do you remember being asked to come up with a solution for that shot?

Ken Ralston: I don’t remember that moment specifically, but the solution was – as dumb as this sounds – the solution wasn’t as complicated as you might think. I mean, pulling it off with the subtlety of what it ended up like was probably the hardest part of it, and of course the concept was really great. The shot did change around quite a bit from the original intent of it until finally it turned into the thing you see.

I love that kind of subtle stuff with effects, which doesn’t happen as often as I’d like – the shot’s over and you have to actually think about it, and you go, ‘Now wait a minute, what just happened is impossible!’ And I thought that was such a great shot to have to design and make work.

A film like Roger Rabbit was challenging not just for its animation but also because of the way it was all optically composited. Can you give us a bit of insight about your stress levels on that film, and generally about that kind of feeling on a production?

Ken Ralston: The whole movie was stressful in a weird way and it only got worse as we got closer to the deadline. On the other hand I’ll have to start off by saying I had been doing a lot of space stuff, but a part of my love of movies has always been animation in the old Warner Bros. style – Chuck Jones, Tex Avery – [and] the great old Disney stuff. So having that job come up was just a godsend. It was the greatest opportunity, I was so excited.

But we killed ourselves for two years, and there you go. I can’t even go into all the different crazy stuff that just added pressure to us to make it worse, like the camera systems that had to be a certain thing to make the movie work. The amount of shots, the jumping around between Richard Williams’ crew in London and the crew here in Los Angeles, and then up at ILM. All I can tell you is that when it was done I was shot to hell along with everyone else. But on the other hand we were so happy with it, and the movie was so much fun. You know, it was all worth it.

You were involved in so many films where live-action motion control was used – films like the Back to the Future series and on Roger Rabbit. Why don’t you think it’s used much anymore?

Ken Ralston: It’s still used, just in different forms. But everything you do on a set that slows down production a little bit or is an added bit of technical nightmare is not welcome, even if everyone knows it has to happen, because shooting on a set is so costly every day. So if you absolutely have to use these systems, then great, it does slow everyone down a little bit and you’ve got nervous studios and people screaming at you and you just ignore it, and you keep going.

Another technology you were heavily involved with was performance capture, starting with The Polar Express. Whatever people say about Polar Express, it was game changing. What are your thoughts on the legacy of that film and actually being in the thick of it at the time?

Ken Ralston: Polar was, well, it went through a lot of transitions. I think now looking at it, despite its horrifyingly scary kids – but that’s not for every shot – it started off with more of an intent to try to capture kind of more of an artsy look like Chris Van Allsburg’s illustrations. It evolved for whatever reasons into something a little more realistic, and I thought it hit a weird hybrid area that wasn’t all that successful. I think a lot of the film looks fantastic and was so hard to do.

A lot of stuff that Bob [Zemeckis] does is right there on the edge and it can either be successful or not. In fact, everyone looks at Forrest Gump and goes, ‘Aha, it’s all great.’ Well, you’re working on a movie and you don’t know that. You don’t know anything. So, on that movie, we were standing in this big empty football field one day and I’m going to put crowds in everywhere later, and Forrest is going to be playing football. I was standing next to Bob and he says, ‘You know, this is either going to be one of the best films ever made or just a grand experiment.’

And I kind of feel that way with a lot of his stuff. Maybe some things weren’t as great as I wished they were in Polar Express. Other things like the environments, the train, certain characters, I think, were fantastic, and it really was pushing the boundaries of motion capture to the limit and beyond. And, brother, that was a very painful thing to do for everybody.

A lot of people concentrate on the performance capture but another side of Polar Express and later Beowulf was the virtual cinematography – coming up with camera moves in cg just as if it was live action. Do you have any memories of how tough that was early on?

Ken Ralston: Well, it really is more work than most people realize. Even watching Jungle Book the other day, you can see that no one [in the audience is] thinking about everything you’re creating. Every pixel, every little rivet in the shot, has to be designed, discussed, textured, lit, rendered – everything’s got to blend together. There’s so much within each frame on those things it is a massive undertaking. It was kind of exciting to be able to suddenly do that kind of virtual cinematography, because I’d done a lot of lighting on miniatures throughout the years, and I had a very good time lighting and playing with the environments and all of that stuff.

Having worked on these big films, were there any other productions you were involved with that perhaps didn’t get made, that you wish had been?

Ken Ralston: Actually there’s several. I can name three right now. Two of them were for Zemeckis that I was really excited about. One was, he was thinking of a very interesting way of telling the story of Houdini, and also he was playing with the idea of a story about Tesla. And I just thought that would be so cool. Especially in Bob’s hands. But who knows why things happen or don’t happen.

All I remember is, I was kind of in the Houdini mode and thinking about how I might design some shots, and I got a call from Bob and he said, ‘So a woman falls down a flight of stairs and she gets her head twisted around a hundred and eighty degrees. How would you do that?’ And I was just kind of like, I didn’t say anything, and then I just said, ‘So we’re not doing Houdini, huh?’ He goes, ‘No, we’re going to do Death Becomes Her.’

The third one was a very small effects film but I loved the project; I don’t even remember the real name of it. It was for the director Taylor Hackford, and it was a true story. It was about a man who had an animal preserve in Africa I believe and the war’s going on, Baghdad’s being destroyed, and he gets word that as always happens in war that the zoo in Baghdad is being decimated. It’s being ignored, the animals are dying. This guy somehow gets there on his own, fights his way to Baghdad, gets through all this mayhem. [The unmade film was to be called Good Luck, My Anthony].

It sort of showed all sides of what was going on there between everybody, all the different factions fighting, and using that center point of the zoo to tell that story. And it really was about creating starving animals, and kind of awful things like that was being asked [for]. But the script was great, I just thought it would have been fantastic, but it never happened. Everyone’s got those stories. There’s always projects you start doing design work on and going so far and then it just poops out. That’s showbiz.

What are you excited about in the future both in terms of technology and also storytelling in visual effects?

Ken Ralston: You know, it changes so radically and constantly and it’s better now than ever as far as what can be asked of you and what you can achieve. I hope to god we never figure out how to do everything. There’s a quote that I’m going to not say exactly right but it’s, ‘the worst enemy of art is the lack of limitations.’ If you don’t have this impossible wall to climb over you get lazy and you kinda sit back and pretty soon everything just turns to shit, and I just don’t think it works.

So having said that, you can do an awful lot in effects now. Things that are problematic – I don’t even think in those terms anymore. I think you can basically do almost anything at this point to some degree and have it relatively successful or brilliantly successful. People always want to bring up the same thing about, hey what about creating Humphrey Bogart in cg and redo Maltese Falcon? I don’t get those stories, I don’t get why anyone would want to see a movie like that. I believe it’s impossible to sustain an entire movie at this point. But if there’s a reason for it at this point, great, I don’t know why there would be, but that’s just me complaining.

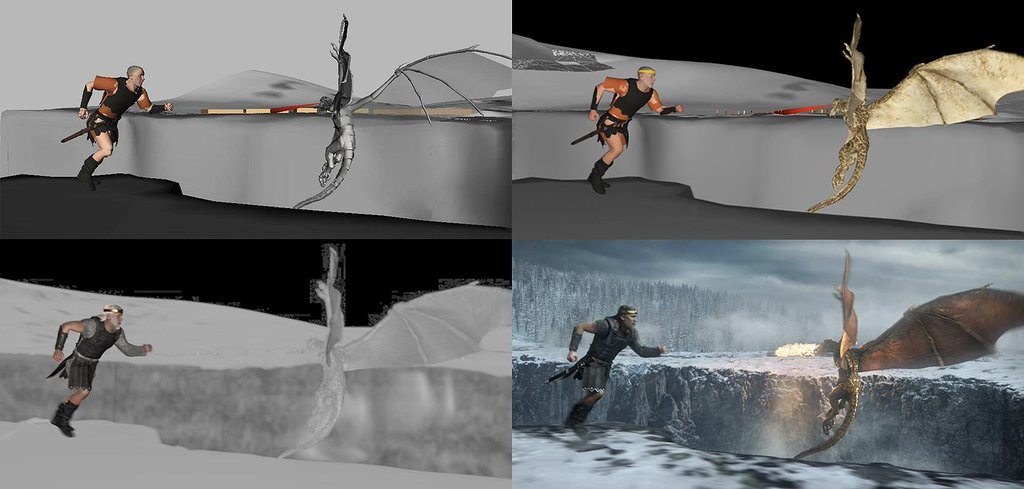

Above: A behind the scenes shot build for “Alice in Wonderland,” for which Ralston was senior vfx supervisor.

Finally, I once heard a talk you were giving where you mentioned the idea of massaging a shot until it was ready, and what struck me about what you said was, it wasn’t some button that gets pressed or it isn’t some killer technique that makes a good visual effect – it’s iterations and it’s artistry in massaging the shot. Do you still think about that a lot?

Ken Ralston: The technology is a tool. Let’s leave it at that. If you don’t have artists, and I mean artists in capital letters doing the work, it will never be any good. I don’t care how many buttons someone creates for you and how many different [pieces of] software, and all the monstrosity of the machine that makes our jobs possible. It’s also something you have to fight a lot so it doesn’t overwhelm the initial work you want to do.

I have always said that when I read a script, and if I get excited about some of it, I’m already getting images in my head, and there’s a fire there, a creative fire. You have that fire at the start. After two years of a movie being slapped around by the machine that’s trying to do that work, if you don’t really work hard to maintain that initial energy and excitement, it will stop you.

A full list of Ken Ralston’s film credits can be found at IMDB.

The VES Awards will be held on February 7th, 2017 at the Beverly Hilton. Marvel Studios Executive Vice President of Physical Production Victoria Alonso will also be receiving the Visionary Award on the night. Read our recent interview with her.