2025 Oscars Short Film Contenders: ‘A Bear Named Wojtek’ Director Iain Gardner

Cartoon Brew is putting the spotlight on animated short films that have qualified for the 2025 Oscars.

In this installment, we’re looking at A Bear Named Wojtek from Scottish filmmaker Iain Gardner. The short earned its Oscars qualification through theatrical exhibition.

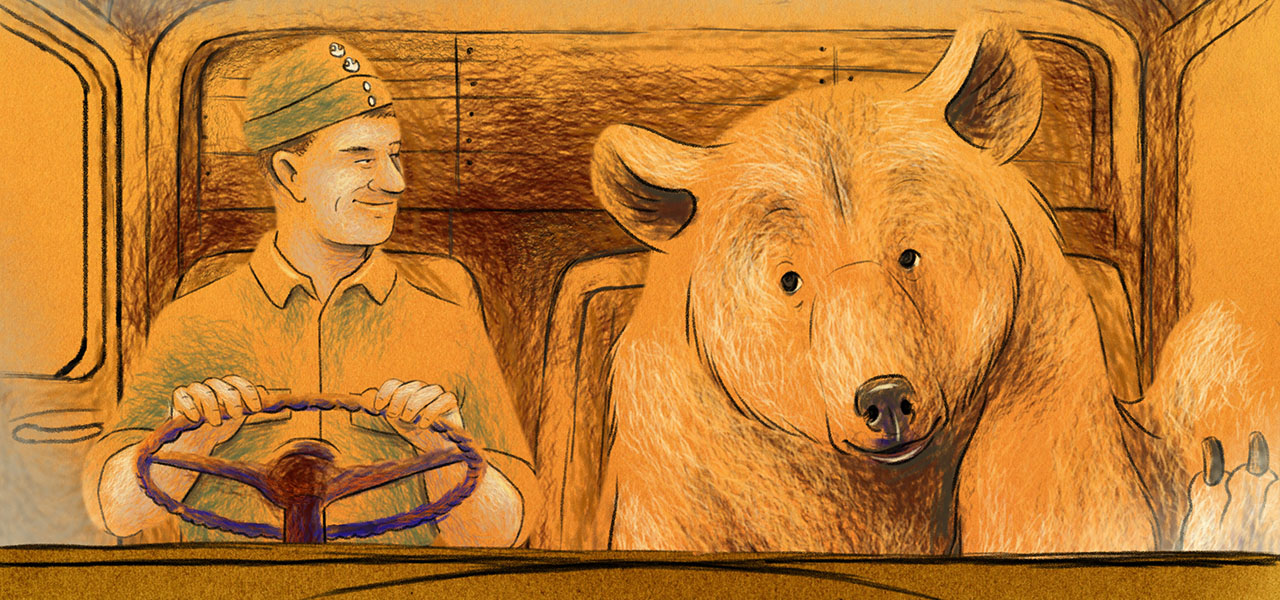

In his heartfelt and wonderfully animated half-hour film, Iain Gardner tells the tale of Edinburgh Zoo’s famous bear, Wojtek. A Bear Named Wojtek takes the viewer on the fantastic journey of this orphaned brown bear brought to Edinburgh, having been previously adopted by Polish soldiers during World War II and who may have played a key role in the Italian campaign at the Battle of Monte Cassino. The film is a British-Polish co-production by Illuminated Film Company, Studio Miniatur Filmowych, Wojtek Animation, Animation Garden, and Running Rabbit Films.

Cartoon Brew: How much has history itself inspired you in your storytelling, and what were the challenges in weaving this tale of a bear soldier between fact and fiction?

Iain Gardner: Understanding the historical context was critical for framing this narrative. I think within animation there is scope to not be ‘accurate’ per se, but at least we can be faithful to the facts. We’ve shared the film with many Polish cultural societies in Britain and I’ve been humbled by their reception. Based on their feedback, I feel confident that we got the balance right of what to include in our telling in a way that honors their experiences and memories, and for it to also make sense for general audiences.

The biggest challenge was compressing complicated World Realpolitik into short bursts within the film – I opted for symbolic or metaphoric sequences to convey these details, many of which aren’t commonly known to general audiences – I fear in part due to those jingoistic war films I watched as a youth! We started this film with the intention of being a warning from history – sadly, during production, world events overtook us and it now feels more like a reflection on contemporary events. I found the whole story fascinating. I have to admit my incredulity in regard to whether Wojtek the Bear carried shells at the Battle of Monte Cassino. For me, this ambiguity is what lends the story to animation – you cross the line slightly into fantasy before crashing back into reality. It’s the symbolism and emotion that become important to express.

What was it about this story or concept that connected with you and compelled you to direct the film?

Like any creative undertaking, it’s a bit of a melting pot of lots of different ideas, experiences, and influences. The seeds go way back to my childhood. My late father (who lived through WWII) would always tune into war films of a certain vintage, generally depicting stiff-upper-lip Brits defeating the rotten Nazis single-handed. So, the presence of stories about war, and WWII in particular, have always been in my life.

Later when I was a student at Glasgow School of Art, I really enjoyed sketching animals. During a visit to Edinburgh Zoo, I was drawn to the polar bear enclosure. I later learned that this enclosure had accommodated a famed bear who saw active service during WWII – Wojtek the Bear! My interest in animals has evolved into reflections on how we mythologize animals to understand or convey aspects of human nature, so I was attracted to the symbolism that Wojtek had come to represent as the embodiment of Poland.

What stirred this melting pot together was the two major referendums which took place in the United Kingdom over the last decade. The first being 2014’s Scottish Independence Referendum, the latter being 2016’s Brexit vote. Both campaigns peddled on perceptions of national identity, and both had different approaches to the voting constituents. Scotland’s vote included anyone who had chosen to live in Scotland, whilst Brexit excluded immigrants. The tone of the Leave Europe campaign, with its ‘Britain can go it alone’ and allusions towards the Second World War resonated with the tone of the films I had watched with my father; therefore I felt compelled to try to redress the balance and recognize the sacrifices other nations made for our freedom during WWII and the respect due to their descendants now living in Britain.

What did you learn through the experience of making this film, either production-wise, filmmaking-wise, creatively, or about the subject matter?

We intentionally initiated this film around a strategy of personal development to enable a core team of Scottish creatives – myself and other award-winning auteurs including Will Anderson, Rachel Bevan Baker, and Ross Hogg – to learn from this longer-form production in addition to instigating an international co-production which, in this case, was with Filmograf in Poland. It was a great opportunity for us all to develop our skills as well as scale-up the ambition of production with a view to producing a feature film, ideally made in Scotland, which could further enhance and retain the talent pool here. Before we started production, I had suspected that you need a robust and practical pipeline, and our production manager Rebecca Warner Perry was key to developing this. My other instinct before starting was to work with people more talented than oneself! Everybody involved from script to final grade elevated my vision, creating something greater than the sum of its parts.

Prior to production, I did a deep dive into the subject matter, the context of the times, and the world of our characters. I also benefited from a writing residence at the Abbaye de Fontevraud which helped me focus on this. I worked really closely with a survivor of the 1939 Russian invasion of Eastern Poland who emigrated to Britain after the War – Krystyna Ivell – who has published an album on Wojtek as well as having staged an exhibition on the bear. I found the research phase the most difficult as it’s quite harrowing to immerse yourself in the horrors of that time – although I’m aware any stress I found is incomparable to the experience of those currently living in war zones today, which unfortunately are becoming more numerous.

Can you describe how you developed your visual approach to the film, why you settled on this style/technique, and how this shaped the final work?

My favorite animator of all time is Frédéric Back. I’ve wanted to make a homage to his style of animation forever! Recent developments in digital animation software made it possible to achieve a sense of his style relatively simply and quickly. Back’s hand-drawn ‘dapple’ process was achieved with the application of Prismacolor pencils on frosted cels, and I always knew that it would be impossible to replicate that within the funding opportunities available to me, combined with commissioning policies which for years have favored innovative approaches to digital aesthetics.

However, TVPaint allowed me to create brushes that created a flurry of ‘dapple’ marks with the flick of the wrist, and a considerably shortened art-working time. We kept the color palettes in each sequence quite monochromatic to minimize the number of color variations we’d have to match in each frame, which I also felt helped underscore the emotional beats of the story. To ensure there was no confusion about my source of inspiration, I invited Frédéric Back’s collaborator Normand Roger to compose the score – which is incredibly beautiful and emotional, if I do say so myself. And it was an absolute honor to work with him: he is so generous and incredibly humble considering his achievements.