2024 Oscars Short Film Contenders: ‘Miserable Miracle’ Director Ryo Orikasa

Welcome to Cartoon Brew’s series of spotlights focusing on the animated shorts that have qualified for the 2024 Oscars. There are several ways a film can earn eligibility. With these profiles, we’ll be focusing on films that have done so by winning an Oscar-qualifying award at an Oscar-qualifying festival.

Today’s short is Miserable Miracle by Japanese filmmaker Ryo Orikasa. The Japan-France-Canada co-production earned Oscars qualification by winning the grand prize at this year’s Ottawa International Animation Festival.

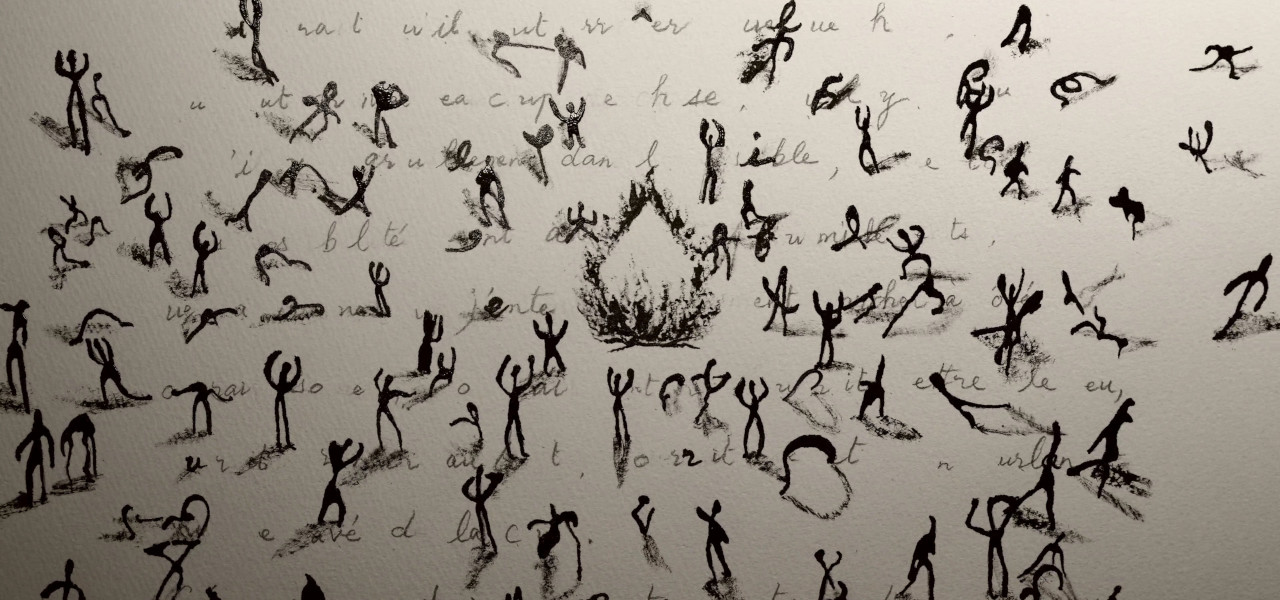

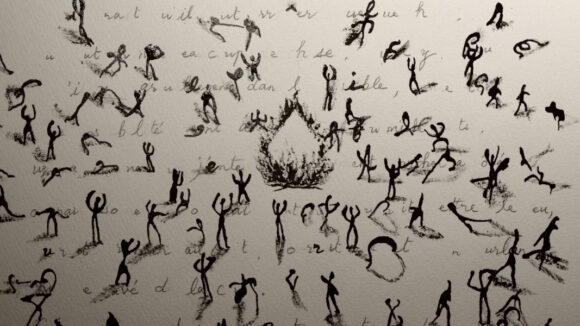

Miserable Miracle is an animated adaptation of the book of the same name by Henri Michaux (1956). The film plays on the limits of language and perception, connecting sound, meaning, shape, and movement. In the short, lines of text from the book fill the screen, vibrate, and morph, with individual letters breaking off and turning to stick figures as a narrator reads the author’s words.

Cartoon Brew: How did you first encounter Michaux’s writing, and what was your initial reaction to his work?

Ryo Orikasa: About 15 years ago, I happened to come across a book by Henri Michaux at a used bookstore in Tokyo, and I was shocked by the evocative power of his writing and the array of surrealistic images. At the same time, the author observes strange situations, but his writing style has a calmness to it, and I was left with a strong and surprising impression that these things could coexist.

What was it about this story or concept that connected with you and compelled you to direct the film?

I think it was inevitable that I would approach the language of poetry. This film depicts surreal scenes, incredible violence, and disaster. To put it in an abstract way, I have an intuition that we cannot use normal language to think about disasters and that we have to reinvent words. In the original text by Henri Michaux, the word “anopodokotolotopadnodrome” appears. I think I was asking myself to create a new language, to be able to accept such a special word as something universal.

What did you learn through the experience of making this film, either production-wise, filmmaking-wise, creatively, or about the subject matter?

The animation production took me approximately five years. In a way, I spent five years reading one text, but over time, reading became difficult because I found too many meanings and images in one word. Being asked to respond to misunderstandings and conflicts is just like real life.

Although it was a small group, it was my first time working with a crew. There were moments of freedom, moments of more open production. Rather than working as a team to create a single image according to the director’s instructions, the image emerged as a result of each team member behaving in their own way. This may be more important than the film itself.

Can you describe how you developed your visual approach to the film? Why did you settle on this style/technique?

The very analog and classic technique of drawing with pencil or ink on paper maintains the connection and intimacy between the image and the physical sensations and emotions that create it. In this project, the size of the paper [that we] used changed seamlessly from approximately 3 cm to 40 cm for each scene. This stems from the fact that it required a material and physical approach rather than a visual one. In other words, the disasters that were to be depicted were not objects of objective observation but rather objects of active, physical experience that produced them.