2024 Oscars Short Film Contenders: ‘Carne De Dios’ Director Patricio Plaza

Welcome to Cartoon Brew’s series of spotlights focusing on the animated shorts that have qualified for the 2024 Oscars. There are several ways a film can earn eligibility. With these profiles, we’ll be focusing on films that have done so by winning an Oscar-qualifying award at an Oscar-qualifying festival.

Today’s short is Patricio Plaza’s Carne de Dios, one of the most successful Latin American shorts to do the festival rounds this year. The film won two Oscar-qualifying awards: Guadalajara’s Rigo Mora award for an international animated short and Chilemonos’ best Latin American animated short.

Set during Mexico’s colonial period, the short follows a Spanish priest who contracts an illness and must rely on traditional native healing methods that he previously condemned. The full short is currently available on Youtube.

Cartoon Brew: Where did the inspiration come from to mix colonial history and supernatural fantasy?

Patricio Plaza: In Latin America, we have a long tradition of what I call political horror as a cinematographic subgenre, and animation has had a significant presence in this field. We also have a long tradition of magical realism both in literature and cinema. It’s kind of natural for us to mix history with fantasy and speak about social topics from a fictional approach that might bring new elements of discussion to them. Also, the history of our continent is so full of political persecution that artists had to find a way to hide messages in non-realistic fiction. Supernatural fantasy was far enough from reality to appease censors while at the same time silently speaking to core problems of our culture. Working with these genres allows us to hide or traffic disruptive ideas under narrative devices that seem distant from our daily lives.

What was it about this story or concept that connected with you and compelled you to direct the film?

While doing research in Mexico, I started relating these stories to what happened during the colonial period of the 16th century. I read documents written by Spanish friars and the edicts of the Inquisition saying that all the native spiritual practices, including the ceremonial use of sacred plants and mushrooms, were an act of the devil. I realized that the demonization of other ways of life and cultural minorities is the common ground of any form of supremacy that is used to justify all types of genocides.

I grew up as a gay kid during the ’80s. I guess I am sensitive to the forms of oppression that all minorities must go through due to religious views, especially the institutionalized monotheistic religions that impose their worldview and moral values on those who simply have other ways of living. The violence over native cultures is one of the most graphic expressions of that persecution.

What did you learn through the experience of making this film, either production-wise, filmmaking-wise, creatively, or about the subject matter?

To stand firm when working with delicate topics, you have to trust your guts, even if that means not pleasing everyone. But to change things always implies pushing some boundaries, especially in such a conservative medium as animation. Part of the transformative nature of art is to make you uncomfortable with the current state of things. I also learned to build an artistic ecosystem where each member of the team contributes to the story and the overall universe of the film with their skills. I couldn’t have done this film without the incredible team that accompanied me with this vision. Almost 100 people from Argentina, Mexico, and Colombia worked on the film and supported it in a collaborative effort. I’m proud of that.

We got rejected by all of the European funds when we requested financial aid. Maybe that was a sign that our film was touching on some topics that are still hard to address in animation, such as the colonial backdrop and its consequences. Now, the film has been released and is doing pretty well at festivals, which means that sometimes you just have to persist with your conviction until the very end.

Can you describe how you developed your visual approach to the film? Why did you settle on this style/technique?

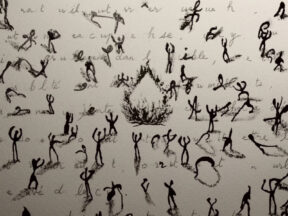

The visual style of the film is heavily influenced by Latin American popular arts, especially comic artists such as Alberto Breccia or Fontanarrosa, painters like Oswaldo Guayasamin, and Mexican muralists. These influences are mixed with Japanese anime and Western animation implanted in our brains during the 1980s and ’90s, as well as author-driven European animation. The character designer Diego Polieri and I worked with those influences to reach a postmodern visual aesthetic that mixes these heterogeneous elements to build a syncretic aesthetic I consider popular. We also included disruptive elements and an “ugliness” in the visual representation of iconic characters. We wanted this rough look in both the visuals and animation to make it somehow grotesque and visually “violent” as opposed to the more fluid and polished line art that is so dominant in 2d animation. With art director Gervasio Canda, we focused on creating a different mood for each scene and building up this transition from a more naturalistic ambiance to the fully hallucinogenic experience that the main character undergoes in his body, which reflects the many stages of this trippy-sexual-iconoclastic-horror experience that we built in the hopes of stirring around a bit the guts of the audience.