INTERVIEW: Masaaki Yuasa On His Creative Process For ‘Lu Over The Wall’

A fanfare of color and dance-inducing music announce the return of Japanese animator and director Masaaki Yuasa, 53, to feature filmmaking with Lu Over the Wall, his first cinematic venture in over a decade.

Long considered an obscure cult favorite, Yuasa’s 2004 feature directorial debut, Mind Game, was officially unavailable in United States, and except to a small subset, his prominence as an artist was relegated solely to his work in anime series. But now that GKIDS has boarded the Yuasa musical train — the indie U.S. distributor has acquired distribution rights to Lu and two other Yuasa films — his wonderfully visionary take on the medium might finally get his day in the sun.

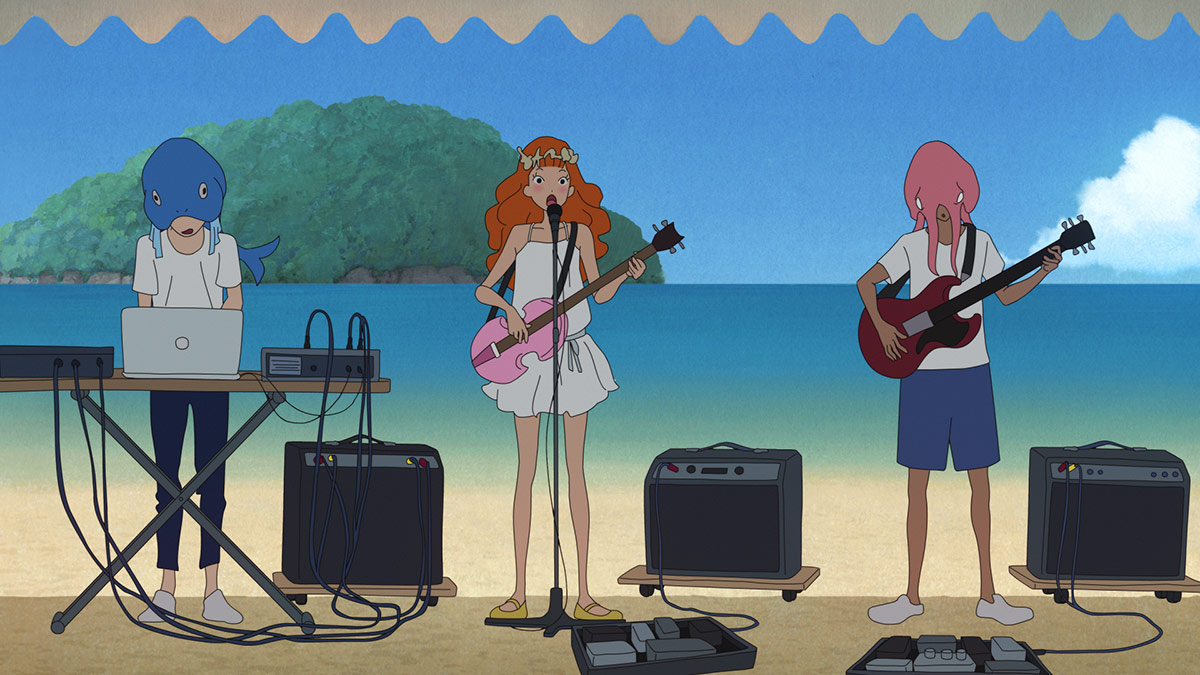

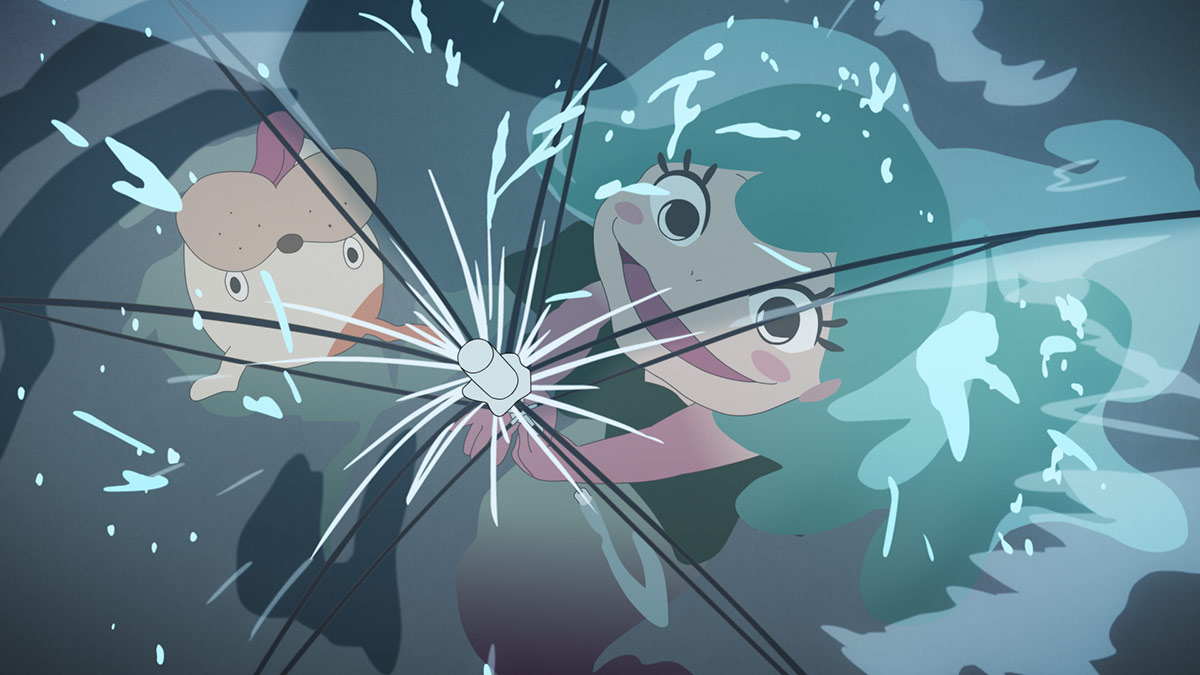

Drawn to inspire sheer joy and the pleasures of letting go of inhibitions, Lu Over the Wall uses the ancient figure of the mermaid in whimsical fashion for an infectiously adorable protagonist. Lu is a young mermaid who is instinctively attracted to music and dance, and when she meets Kai, a shy teenage boy who has reluctantly accepted to be part of a band, a playful friendship develops between them.

The town; however, has a more sinister perspective on the mystical creature, and believe that harm will come their way as long as the mermaid hangs around. Memorable characters populate this musically driven fable like Lu’s pet, the huggable Merdoggie, or her sharp-toothed father, who is essentially a shark in a suit. Few animated features this year will be as big-hearted, imaginative, and cheerful as Yuasa’s latest.

Cartoon Brew sat down with Yuasa at the Sundance Film Festival last January, where Lu Over the Wall screened in the Sundance Kids section, to discuss his return to family-friendly content and the singular approach to dance and fluid movement in his work.

Cartoon Brew: Lu Over the Wall is a much more family-oriented film in comparison through your previous feature work. Why did you decide to target younger audiences now?

Masaaki Yuasa: When I started my career, most of my work was in family shows like Shin Chan and Chibi Maruko, but when I became a director, I was only offered projects that were not for children. That’s why I wanted to do Lu — to make something for families. After a break from doing a lot of these projects, this was a move to go back to this idea of being able to do something appropriate for children. For this, I got inspiration from a lot of meant-for-children animation, like Chibi Maruko and other such anime.

How did the decision of making your protagonist a mermaid come about? Is that something that was of interest to you beforehand, or did you think it was interesting to tell a story about mermaids in a different way?

Masaaki Yuasa: Twenty years ago I was thinking about vampire stories, and then this one turned into a mermaid story. I wanted to have the main character be cute, but also a little bit scary. A mermaid can still have this core cuteness, while also accessing a lot of more scary sides. In addition to that, I was really interested in exploring mermaids because there are so many vampire stories and they’re overdone. Mermaids are in between cuteness and scariness. I liked the idea of taking another creature that can carry both of these qualities, so that’s why I migrated to doing a mermaid story.

Before anything was drawn or shot, what was the core theme or concept that inspired Lu Over the Wall beyond how much fun it is? You have a young man who seems to be unable to express himself.

Masaaki Yuasa: I wanted to share with the audience something about what’s happening nowadays in Japan, where younger generations don’t want to say what they really think. If they don’t like something, they just don’t say it. They don’t want to communicate – things like that. They keep it to themselves. I want to give them the idea that you can say whatever you want. It’s ok to say what you think. That’s what Kai needs to do.

Lu inspires him, because she’s very often expressive. Eventually he opens his mind to that, and he can say what he wants to say. At the end we see him singing, and that’s what he really wants to do. He is also able to say, “I love you.” Kai goes through a process of not being able to say his true feelings, but by the end of it, through Lu’s influence, he is able to [express] his true feelings. This is related to this idea that a lot of younger Japanese people are just not able to say what they truly feel, so I wanted to create this inspiration, create this story though the mermaid story context, where somebody is able to find their voice and share their true feelings.

There are elements in the film that point to the relationship between humans and nature, in particular with the ocean. What does this contrast between the human world and the power of nature represent for you?

Masaaki Yuasa: There is a contrast between the town, the sea, and nature. Nature is kind of wild, there is freedom, and it’s also scary. But without trying that wildness, those scary things, then there’s no change. Kai wants to be with the mermaid, because the town is very conservative; they don’t want to change, they just want everything to remain as it is. Then the mermaid appears, and things start to change. That’s why I wanted to set it by the ocean, because it carries this element of freedom.

The town is afraid of this freedom, of this exploration, despite being immediately next to the ocean. I thought this was a good contrast, and a good pairing to put together in terms of constructing the space for the story to take place. Having the mermaid come into that space really brings the town out into this freedom, and also into this scariness that the ocean has.

Can you talk about the musical aspect of Lu Over the Wall? It’s a huge element in this story and how the characters relate to each other.

Masaaki Yuasa: It wasn’t really planned from the beginning. As I was working on the story, it sort of developed with the music. In the end, the main character’s journey is defined by music. The final song especially carries this element that induces dance, which brings forward the kind of freedom that I was trying the push the town towards. I originally set the town up to be this staunch, scared place, and it’s only with the final song when everyone is really able to let loose. First Kai and then everyone else is dancing. That final song encapsulates the freedom that Lu brings to the town. The lyrics in the song I decided on say exactly what I wanted it to say.

You have two projects being released almost back to back after a long gap between feature projects. What has changed in terms of the way you are developing your films now that you have your own production company Science Saru?

Masaaki Yuasa: One of the reasons they are coming out one after another is because at Nippon, the studio, we’re producing a lot. Also, I don’t want to have long periods of time in between projects anymore. I want to continue to work on projects, rather than take long breaks in between projects. I want to keep the creative process going by moving quickly from one project to the next.

It’s also because since we founded Science Saru we have to keep working anyways, so it keeps the energy going and it keeps this constant forward movement and process of ideas happening inside the studio. Basically, I want to make one movie per year, not taking three years to make one film. That is our goal. We want to reach out to the audience and make one film per year. Right now, we have three projects that are coming out between 2017 and 2018, but we’ve been working on them for like three years. Also, I don’t want to have huge budgets and make something over a long period of time. If you have less of a budget, you have more freedom, and you just keep creating.

Tell me about the style of animation in Lu Over The Wall. The characters are very fluid. The way they move truly resembles the way water moves, especially when they dance.

Masaaki Yuasa: I really like old animation, even like Disney or Western animation, and also including old Japanese animation. A kind of unrealistic animation, deformed, the kind of squash and stretch sort of fluid movement. I like the way that characters who move more fluidly can carry more emotion by not being as realistic in their movements. There’s the freedom to add more emotion to the movement by not sticking to what is strictly realistic. For example, in some realistic movements, like if the character is holding a cup, I want to show it in very simplified movements, so the audience understands he’s holding a cup. Visually it might not be very realistic, but I want to find the best way to communicate with the audience to show that movement clearly.

For the dance sequences, like what you did in Mind Game, you ditch realism and these moments become exaggerated, nearly surreal. What’s the motivation behind approaching dance on screen in this manner?

Masaaki Yuasa: Especially the dancing parts, I wanted to make them look like everyone was really high, but if you make the characters seem high like a real human, it’s not very exciting. That’s why you have to accentuate it in animation. By having the dance be specifically even more unrealistic than the rest of the movement in the film, I’m able to bring more emotion into that one dance and to really carry home how strong the emotion, and how strong this feeling of lightness and joy is within all of the townspeople, when they’re going into this big, crazy, unrealistic dance sequence.

When you look at kid’s drawings, if the kid likes the nose, the kid draws it really big. If the person really likes flowers, the flowers motivate the drawing. This isn’t logical, but it’s more emotional in terms of how you get the impression of the thing. That is a reflection of how I think about dancing. It’s the idea that, if a child loves flowers, the child will draw them bigger. It’s the same here, where I love the dancing animation sequence, so that’s going to be bigger and louder and become the most accentuated sequence.

Do you enjoy the writing part of the filmmaking process? As an artist I’m sure you enjoy drawing, but how do you engage with the writing?

Masaaki Yuasa: Before, I used to draw more, but nowadays I really like writing. The best way for me to make films it to write the same way I do my drawings. Sometimes, you have really good writing, but it doesn’t translate well to animation. It has to match with the images, so I try to work on both the writing and the visual at the same time. I don’t make storyboards, but I make sketches. I draw key inspirational shots, creating the landscape, creating the general idea of how I would like things to look, while also creating the script. This is not strictly a storyboard, but more visual cues. For example, if there is an image at the core of what I’m writing, being able to have that as one drawing, to visually reflect that while I’m doing the script, is very helpful.

Since you’re now a director and have a studio, do you still get to animate?

Masaaki Yuasa: I don’t draw exactly, but we have a process where I do adjustments to correct the images. I’m not precisely drawing as I used to, but I’m still doing a lot of fixing, a lot of checking things off for animation. I have to communicate a lot of things with drawings, because it’s kind of difficult to express everything verbally. I have to do a lot of drawings sometimes.

Are you excited for more people in the United States to know about your work, now that GKIDS is distributing your features Mind Game, Lu, and Night is Short, Walk on Girl?

Masaaki Yuasa: My personality is like Lu’s, so I’m very happy that people are watching my film here. I’m delighted. The more people watching them, the happier I am. I’m very happy to bring my work to the U.S.

Lu Over the Wall opens nationwide in U.S. theaters this Friday, May 11, through GKIDS.

.png)