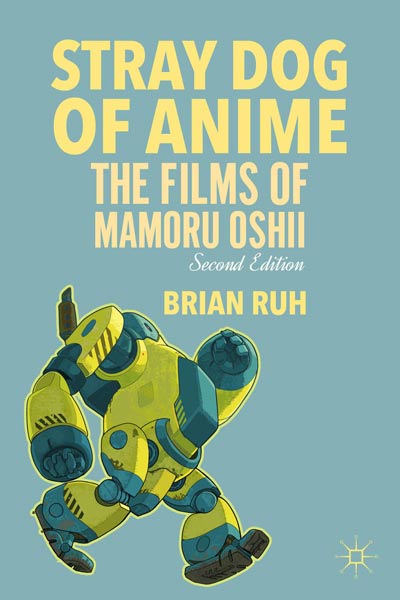

Book Review: ‘Stray Dog of Anime: The Films of Mamoru Oshii’

Stray Dog of Anime: The Films of Mamoru Oshii

By Brian Ruh.

(Palgrave Macmillan, 332 pages, $30)

Order: $28.50 on Amazon / £16.99 on Amazon UK

I can remember looking at anime titles in British video catalogs back in the Nineties; as the pastoral fantasies of Hayao Miyazaki would not reach prominence in this country until the new millennium, UK distributors placed a strong emphasis on futuristic thrillers. The films of Mamoru Oshii certainly fit that bill.

It is fitting to consider, then, that Miyazaki and Oshii have something of a friendly rivalry. Oshii jokingly compared Studio Ghibli to the Kremlin, while Miyazaki later told an interviewer that, “Oshii and I are friends, so we always dis each other.” There are many ways in which they can be contrasted: Miyazaki’s films celebrate nature, while Oshii’s explore high-tech urban landscapes. Miyazaki looks back towards a bygone childhood, while Oshii imagines the future. Miyazaki expresses regret that computers are encroaching upon real life experience, while Oshii is fascinated by the interplay between cyberspace and psyche.

They even have competing tastes in animals. Miyazaki is famously fond of pigs; Oshii, meanwhile, likes to include dogs in his films – and has identified himself as anime’s “stray dog.”

Originally published in 2004 and now available as a revised and updated edition, Brian Ruh’s Stray Dog of Anime: The Films of Mamoru Oshii is an attempt to give the director the recognition amongst English-speaking viewers that he deserves. Ruh wants to make it clear that Oshii is not merely the man behind the Ghost in the Shell films, but an accomplished auteur with a varied filmography.

Each chapter in the book is dedicated to an Oshii film, ranging from his early work on the Urusei Yatsura anime to his 2009 film Assault Girls. In the process, Ruh underlines Oshii’s recurring themes: dreams and reality, Christian theology (the book contrasts anime such as Neon Genesis Evangelion, which use Biblical iconography as a fetching motif, with Oshii’s deeper treatments of the matter) and anti-authoritarian representations of the police and military.

It is also interesting to see how Oshii engages with developments in anime and its culture. His series Dallos was the first OVA anime, while the international success of Ghost in the Shell allows Ruh to discuss the topic of techno-orientalism. Oshii’s work eventually begins to take on a self-reflexive element: he clearly has an interest in making anime that is about anime.

Above all, the general picture is of a filmmaker who drifts between acting as a journeyman director knocking out solid work in popular genres, and moonlighting as a more cerebral and innovative artist. Oshii comes across as someone who likes to take his previous films and slice them open, reading their entrails and using his findings as the basis of subsequent, more intertextual works.

Admittedly, Ruh makes a few questionable decisions in terms of structure. Each chapter contains a lengthy plot synopsis and capsule character biographies; as these dry stretches serve only to repeat information available online, the space could have been out to better use. The one-film-per-chapter format means that Oshii’s lesser-known works fall by the wayside: there would have been much to analyze in Talking Head, a quirky 1993 live action film about a series of murders in an anime studio, but Ruh gives it a single paragraph and a brief mention later on. Meanwhile, Blood: The Last Vampire—a film on which Oshii served only as supervisor—is discussed at length.

Still, the occasional flaw is not enough to hamper the book. Stray Dog of Anime: The Films of Mamoru Oshii is a solid and wide-ranging look at a director who deserves to be recognized for more than just scantily-clad cyborg women.

Order Stray Dog of Anime: The Films of Mamoru Oshii on Amazon.com or Amazon UK.