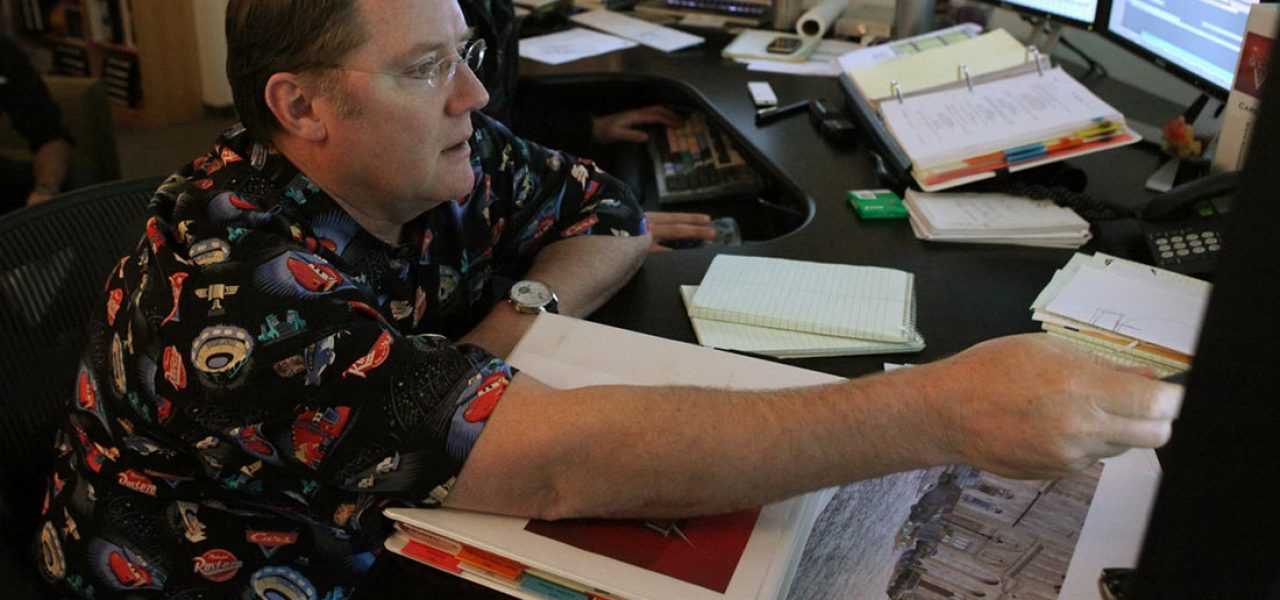

Learn Three Storytelling Tricks From John Lasseter

Animation director John Lasseter was born on this day, January 12, in 1957. Now 60 years old, he is as influential as he has ever been, not only steering the creative team at Pixar, the studio he helped build, but also Walt Disney Animation Studios, where he serves as chief creative officer.

Lasseter, who won two student Academy Awards and one regular Academy Award before he even directed his first feature film, has a knack for communicating ideas to audiences. Unlike many filmmakers, however, he rarely discusses his creative philosophy in public interviews. So, in honor of his birthday today, we’re presenting some rare insights into his storytelling craft that Lasseter shared during a SIGGRAPH ’94 paper entitled “Tricks to Animating Characters with a Computer.”

The examples that Lasseter cites in this talk are taken from his early shorts (Luxo Jr., Red’s Dream,) but at the time of the talk, he was deep into the production of his first feature, Toy Story. As such, we can view this advice as representative of the ideas that he was applying in the production of that trailblazing film, which would soon revolutionize the animation industry and lead us to where we are today.

1. A Story Trick

In storytelling, the timing of ideas and actions is important to the audience’s understanding of the story at any point in time. It is important that the animation be timed to stay either slightly ahead of the audience’s understanding of what’s going on with the story, or slightly behind. It makes the story much more interesting than staying even with the audience. If the animation is too far ahead, the audience will be confused; if the animation is too far behind, the audience, will get bored; in either case, their attention will wander.

Action timed to be slightly ahead of the audience adds an element of suspense and surprise; it keeps them guessing about what will happen next. An example of this is at the beginning of Luxo Jr. Dad is on-screen, alone and still; the audience believes they are looking at a plain inanimate lamp. Unexpectedly, a ball comes rolling in from off-screen. At this point, both Dad and the audience are confused. The audience’s interest is in what is to come next.

When the action is timed to be slightly behind the audience, a story point is revealed to the audience before it is known to the character. The entertainment comes in seeing the character discover what the audience already knows. Another application of this is with a dim-witted character who is always behind; the audience figures it out before he does.

Many of these tricks can be used in concert in any given scene in order to achieve the strongest impact on an audience. At the end of the dream sequence in Red’s Dream, Red juggles three balls and catches them with a big finish; the crowd explodes into wild applause, and Red takes his bows. Slowly the circus ring dissolves to the interior of the bike shop, the sound of the applause fades into the sound of rain, and Red, unaware, continues to take his bows. At this point, the audiences has not caught on to what is happening because the timing of the action is slightly ahead of the audience. As the room appears, so does the large”50% OFF” tag hanging from Red’s seat. The animation of the tag is timed to be light in weight; it flops around more actively than anything else in the scene. This contrast of action directs the audience’s attention to the tag which is a subtle reminder that Red is still in the bike shop. The audience is now ahead of the character and watches Red discover where he really is. Red’s actions were timed to be slow, accentuating his sad emotion. Timing made the story points clear, the emotion stronger, and the character’s actions were a result of his thought process; thus, the scene has a strong impact on the audience.

2. Emotion Determines Pace of Action

The personality of a character is conveyed through emotion and emotion is the best indicator as to how fast an action should be. A character would not do a particular action the same way in two different emotional states. When a character is happy, the timing of his movements will be faster. Conversely, when sadness is upon the character, the movements will be slower. An example of this, in Luxo Jr., is the action of Jr. hopping. When he is chasing the ball, he is very excited and happy with all his thoughts on the ball. His head is up looking at the ball, the timing of his hops are fast as there is very little time spent on the ground between hops because he can’t wait to get to the ball.

After he pops the ball, however, his hop changes drastically, reflecting his sadness that the object of all his thoughts and energy just a moment ago is now dead. As he hops off, his head is down, the timing of each hop is slower, with much more time on the ground between hops. Before, he had a direction and a purpose to his hop. Now he is just hopping off to nowhere.

To make a character’s personality seem real to an audience, he must be different than the other characters on the screen. A simple way to distinguish the personalities of your characters is through contrast of movement. No two characters would do the same action in the same way. For example, in Luxo Jr., both Dad and Jr. bat the ball with their heads. Yet Dad, who is larger and older, leans over the ball and uses only his shade to bat it. Jr., however, is smaller, younger, and full of energy, he whacks the ball with his whole shade, putting his whole body into it.

3. Ask Why

In every step of the production of your animation, the story, the design, the staging, the animation, the editing, the lighting, the sound, etc., ask yourself why? Why is this here? Does it further the story? Does it support the whole? To create successful animation, you must understand why an object moves before you can figure out how it should move. Character animation isn’t the fact that an object looks like a character or has a face or hands. Character animation is when an object moves like it is alive, when it looks like it is thinking and all of its movements are generated by its own thought process. It is the change of shape that shows that a character is thinking. It is the thinking that gives the illusion of life. It is the life that gives meaning to the expression. As Saint-Exupéry wrote, “It’s not the eyes, but the glance—not the lips, but the smile…”

Every single movement of your character should be there for a purpose, to support the story and the personality of your character. It is animation after all and any kind of motion is possible, and in the world of your story any kind of rules can exist. But there must be rules for your world to be believable. For example, if a character in your story can’t fly and then all of a sudden he can fly for no reason, your world and story will lose credibility with your audience. The movement of your character and the world of your story should feel perfectly natural to the audience. As soon as something looks wrong or out of place, your audience will pop out of your story and think about how weird that looked and you’ve lost them. The goal is to create a personality of a character and a storyline that will suck your audience in and keep them entertained for the length of your film. When a film achieves this goal, the audience will lose track of time and forget about all their worldly cares. For all that any audience truly wants is to be entertained.

.png)