Seven Decades Of Animation: The Rock & Roll Career Of ‘Heavy Metal’ Director Gerald Potterton

Gerald Potterton didn’t work for Disney, Fleischer, Warner Bros., or MGM during the golden age of animation, so he is not as prominent in the coffee table books about the art form as others of his generation.

But he holds an important place in animation history – having played a part in the production of countless animated films that have become cultural touchstones to generations, from the first British animated feature to Yellow Submarine to Heavy Metal. More importantly, he is still active at 91, and busy working on animation projects.

Early Life And Career

Potterton was born in Tooting Bec (south London) on March 8, 1931. His father was a musician and his uncle managed the London Palladium theatre. As a teenager, Potterton worked occasionally as a film extra at the Ealing, Elstree-Borehamwood, and Pinewood studios. He later attended Hammersmith Art School, and in 1949 he started a two-year stint with the RAF for his national service.

After Potterton was released from the service, a neighbor who worked at the Halas & Batchelor studio suggested that he apply there. The studio was gearing up for Animal Farm and Potterton would spend two years as an assistant animator on the film, which was released in 1954 as Britain’s first animated feature.

Potterton had ambitions to write and direct his own films and co-founded a cooperative that helped London-based animators with their personal projects. They called themselves the Grasshopper Group and included animators Bob Godfrey and Norman McLaren, who was starting to make waves at the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) with his Oscar-winning short Neighbours. Potterton co-directed his own short at that time, Two’s Company (1953), using the pixilation method.

O Canada

In 1954, Potterton emigrated to Canada and joined the NFB in Ottawa. Shortly after, the NFB relocated to Montreal. Potterton didn’t settle entirely after moving to Canada however, and regularly made trips back to the U.K. for work and leisure.

He was back in the London in 1955 to help Eddie Radage start up his commercial studio on Savile Row. Potterton also helped another young filmmaker, Richard Williams, with storyboards for what would become Williams’ first animated film, The Little Island (1958).

Jumping across the pond to Canada again, Potterton wrote and animated Spoilage Control (1956), a short film about proper control of fish spoilage which turned out to be entertaining and well executed, with a graphic style similar to United Productions of America’s (UPA) shorts.

Potterton left Canada and the NFB in 1960 and went to New York City to work at the commercial house Lars Calonius Productions. Calonius’ hope was that Potterton would take over the studio, but instead Potterton ended up going back to the NFB in Montreal after just one year.

Breaking out at the NFB

The 1960s proved a break-out decade for Potterton. Two of his animated shorts, My Financial Career (1962) and Christmas Cracker (1964), were nominated for Academy Awards.

He also wrote and directed the remarkable extended short The Railrodder (1964), starring Buster Keaton. The idea for the film came to Potterton when he saw a stranger’s head zip by him on an overpass. The person was on a railway speeder, and Potterton thought it made for a good sight gag so he quickly drew out some ideas in his ever-present sketchbook.

It was only later that Potterton thought of Buster Keaton and asked if the senior actor would be interested in the project. Potterton had grown up just after the time of silent comedies, but for him, as for many animators, comedians such as Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Laurel and Hardy were idols and muses.

Building His Own Studio

In 1967, Potterton started his own studio, Potterton Productions, in Montreal. George Dunning, an acquaintance from London, asked him to do some work on Yellow Submarine (1968), so Potterton did layout for the Liverpool sequence.

Shortly after, he made the television special Pinter People for NBC, which broadcast in April 1969. It was a compilation of several short stories based on the work of playwright Harold Pinter, connected by interviews with Pinter.

It was during the production of Pinter People that Potterton met and befriended British actor Donald Pleasence, a relationship that would bear fruit throughout the years. Potterton wrote and directed the live-action film The Rainbow Boys, which starred Pleasence, and Pleasence wrote a children’s book called Scouse the Mouse, which Potterton illustrated.

During the 1970s, Potterton produced three animated films based on stories by Oscar Wilde. One of them, The Selfish Giant (1972), received an Oscar nomination. During that decade, Potterton also worked with Richard Williams on Raggedy Ann & Andy: A Musical Adventure (1977) as associate director.

Heavy Metal and Beyond

Potterton went 180 degrees in the opposite direction for his next project, taking the helm for the cult classic adult sci-fi anthology film Heavy Metal (1981). He also continued to produce and do story work on many children’s animated television series such as Rubik, the Amazing Cube and The Wizard of Oz in the mid-1980s.

In his fifth decade in the industry, Potterton created and produced The Smoggies (1991), a television series that promoted environmental responsibility which has been translated and shown in countries all over the world. Interestingly, Potterton says that The Smoggies was the first time he made “real money” from a production – the benefit of being the creator.

Settling Down… Kind Of

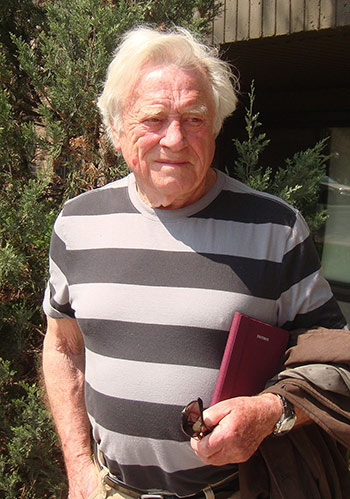

Potterton is now 91. He lives on a farm about an hour east of Montreal and only 15 miles, as the crow flies, from the U.S. border. He keeps busy with his art, grows garlic, and flies radio-controlled model airplanes of all sizes and vintages.

He paints, often with the theme of vintage military planes, and is creating a narrated storybook for distribution on the internet. He is also working towards developing Scouse the Mouse into a feature-length animated film.

Reflecting on his years working in animation and the myriad of changes to the industry over that time, he says the single key to quality filmmaking is the importance of story. Being able to tell a good story is the best way to stand out and build your own career, Potterton says. Teamwork and openness to new ideas are also paramount, Potterton adds. “None of these things you do on your own,” he says.

Although he admits that story is king, Potterton sometimes wishes he had been a better draftsman. He is reminded of two things that Richard Williams told him, “Whatever you do… learn to draw the human figure,” and, “Always bend the horizon line.” Words to live, and draw, by.