Remembering J.P. Miller

Here at Cartoon Brew, we are pleased to present this exclusive remembrance of animation/illustration legend J.P. Miller, who recently passed away at age 91. This is the eulogy that was delivered at Miller’s funeral. It is written by his brother, George Miller, and is reprinted with kind permission from the family.

A Remembrance of John Parr Miller

by George Miller

Thank you for coming to honor John. I’m glad to see that some of you here were fortunate in growing up under the spell of “Uncle John,” that surprising adult who was in some ways a child, too. John, himself, was fortunate in having many such nephews and nieces — whether or not there was a blood connection.

Thank you for coming to honor John. I’m glad to see that some of you here were fortunate in growing up under the spell of “Uncle John,” that surprising adult who was in some ways a child, too. John, himself, was fortunate in having many such nephews and nieces — whether or not there was a blood connection.

There are others here for whom John’s Turtle Bay apartment served as an oasis while running errands in the City. And at twilight, a haven where talented, amusing and gentle people gathered to entertain one another. We might hope, too, that in this large and airy church there may be room for the spirits of John’s many life-long friends who have passed on before.

So, let us now remember John Parr Miller — not in the garb in which he left us — but as he was when we were all much younger.

Not all of you know that his start in life was unpromising and often painful. His adored mother died when he was fourteen — and six years later his father followed her. Also, John was embarrassed by his own height, which never topped five-foot-five. A victim of school yard bullies, he was sure — well into his adult life — that his physical stature would mark him for failure.

Although John had an inquiring mind, it was generally out of synch with school curricula, and I’m not certain that he ever earned a high school diploma. This fact will come as a surprise to those who remember the hundreds and hundreds of volumes he amassed, his sizable music library and the boundless range of his intellect.

As we all know, John’s handicaps — whatever they were –melted before his passion for art and the merciless eye with which he judged his own work.

So, in the company of his new family — that is to say, my widowed mother and my two-year-old self — he headed out to Hollywood, during the depths of the Great Depression. My mother shoved this retiring young man out the door with the portfolio he had assembled in art school and told him to find work. And he did. With Walt Disney’s budding studio, only four years after the birth of Mickey Mouse.

John was assigned a place among the rows and rows of drawing boards occupied by those at the bottom of the food chain — the in-betweeners. The reason there had never been a full length cartoon feature until Snow White was that producing even the usual five-minute short entailed enormous toil. Film races through a movie projector at 24 frames per second, and every one of those frames must be painted. If an animator were to draw a figure with a raised arm and then again with the arm lowered, the in-betweener (John) filled in all the intervening positions. So, John, who in his school days had been looked after by a butler, a cook and a maid, now found himself on the assembly line in what was known by all as the “black hole.”

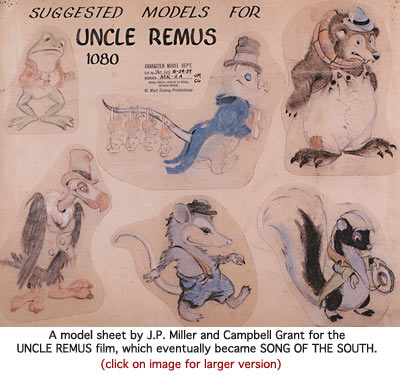

Fortunately, the magnitude of his talent was quickly recognized, and he soon escaped that drudgery, climbing successive rungs until at age 24 he was tapped as one of the three founding members of the elite Character Model Department. Its purpose was to bring Snow White to completion and conceptualize the string of features that would follow. That meant designing the characters and providing other Disney artists with a vivid sense of the mood and atmosphere of each movie’s settings. To quote one film historian…

A member must have a knowledge of the architecture of all periods and nationalities. He must be able to visualize and make interesting a tenement or a prison. He must be a cartoonist, a costumer, a marine painter, a designer of ships, an interior decorator, a landscape painter, a dramatist, an inventor and an acoustical expert.”

Disney couldn’t have found a better man than John. He contributed in this fashion to every feature from the historic SNOW WHITE to PINOCCHIO, FANTASIA, DUMBO, THE RELUCTANT DRAGON and SALUDOS AMIGOS. Disney was famously reluctant to credit work to others. And likewise, John hated to acknowledge anything he ever did for Disney.

Most of you got to know John after his tour in the Navy making training films. That’s when he cut himself loose from Disney and asserted his own style as a freelance illustrator.

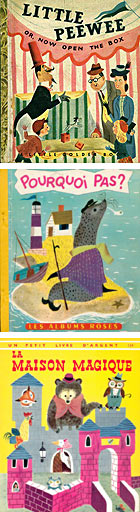

George Duplaix, the founder of Golden Books, recruited John and several other Disney veterans to join the revolution he was fomenting in children’s literature. He wanted to open up a mass market and to enlist artists who would bring a fresh and exciting style to the field — beyond the blandness of “Dick & Jane” primers. The idea caught on, and other publishers jumped in, churning out hundreds of titles — many with the shelf life of a mayfly. But not John’s. He never made a deadline on time. And he never turned in a book without first working all through the night. Because in his eyes the work was never good enough.

George Duplaix, the founder of Golden Books, recruited John and several other Disney veterans to join the revolution he was fomenting in children’s literature. He wanted to open up a mass market and to enlist artists who would bring a fresh and exciting style to the field — beyond the blandness of “Dick & Jane” primers. The idea caught on, and other publishers jumped in, churning out hundreds of titles — many with the shelf life of a mayfly. But not John’s. He never made a deadline on time. And he never turned in a book without first working all through the night. Because in his eyes the work was never good enough.

That perfectionism remains his legacy. Even though it’s been ten years since he completed his last book, his work is so timeless that six titles are still in print. One of them — first issued 50 years ago — has become Golden’s number 3 best seller since its recent reissue. Three more titles are soon to be re-released. And another 41 enjoy an active after-life as used books on the Barnes & Noble website. This month the Donnell Library (opposite the Museum of Modern Art) displayed John’s work as one of the pioneers of the Golden Books revolution.

Although no obituary has yet appeared [note: since this was written, the NY TIMES has published one], the word has spread, and I’ve received letters from other artists that neither John nor I have ever met.

One, Bob Staake, said…

As a child I was enthralled by J.P. Miller’s art. That I hoped I would grow up to become an illustrator as well is a testament to the inspiring nature of your brother’s talent. My biggest regret is that I never had the chance to meet JP face to face and tell him how his art affected me — and how it still does.

And from Dan Yaccarino…

I am an illustrator and JP’s work has been a source of inspiration to me throughout my career. Whether or not he was aware of it, his work was brilliant. It continues to challenge me to push my own work farther. I just finished my first Golden Book and the most exciting part of it was that I am now able to be associated with the great JP Miller.

So, what should we — who did know John — remember of him. That just as John was not an “accidental” artist, neither was he accidentally charming. He applied the same insight and creativity to surprise and delight us. When he gave a child a piggy bank, he would include a sack of 100 pennies. When he borrowed a friend’s county house, he left in the back field a life-size cut-out of a reclining cow. When I — as a 15 year old transplant from Southern California — was invited to share his harbor-front apartment in Provincetown for a whole summer, the amenities included a small sailboat he had bought for me, sailing lessons at a nearby wharf and a neighborhood kid as a sailing pal, who is now my oldest friend.

During the long and difficult years that followed his marriage, many of you came to his rescue, opening your homes to him for extended stays and providing counsel and the comfort of moral support. Although John always doubted his own talents and magnified his modest failings, I hope that through these kindnesses returned he came to realize that –in all respects — he was a very worthy man.