Unpacking The Creative Process Of ‘Negative Space’

In order to produce Negative Space, a gorgeous stop-motion short that illustrates a father and son’s shared ritual of perfectly packing a suitcase, Ru Kuwahata and Max Porter were forced, rather appropriately, to get quite good at the art of packing themselves. By the time the Baltimore-based animation duo wrapped their project in Vendôme, France, they had relocated their entire operation no fewer than four times.

Together, Kuwahata and Porter make up Tiny Inventions, the award winning animation studio responsible for Perfect Houseguest and Between Times, the latter of which won more than 15 awards during the 2014-2015 festival circuit.

The pair’s latest film, currently short-listed by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in the animated shorts category for the 90th Academy Awards, is inspired by a prose poem by Ron Koertge. “My dad taught me to pack,” begins the poem, which also provides (with minor alterations) the script for Negative Space. Kuwahata, in particular, was drawn to the poem’s story, which reminded her of her own childhood and watching her pilot father pack for trips.

After about a year of development, during which Kuwahata and Porter nailed down storyboards and began construction on sets and puppets, the pair moved to France to complete production. It was not their first experience working in Europe; Kuwahata and Porter spent about half their time on production of Between Times in residency at the Netherlands Institute for Animation Film.

“I was always looking for a way to go back to Europe,” says Kuwahata.

“I think in the United States short films are often thought of as a stepping stone leading to something else, or something that you do in your free time in between commercial jobs or other types of work,” adds Porter. “We just felt that there was a respect for short films as their own entity in Europe, and we wanted to be a part of that.”

True to their expectation, they managed to secure a number of grants in France, including a residency at Ciclic Animation in Vendôme, which provided spaces to live and work, as well as production funding. After teaming up with producer Ikki Films and co-producer Manuel Cam Studio, Kuwahata and Porter also applied to anything and everything affiliated with or provided by the Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée, an agency of the French Ministry of Culture.

“We would’ve made it whether we had support or whether we didn’t,” says Porter, but thankfully, in the end, they had the financial backing of about 10 various sources, most of which were based in France.

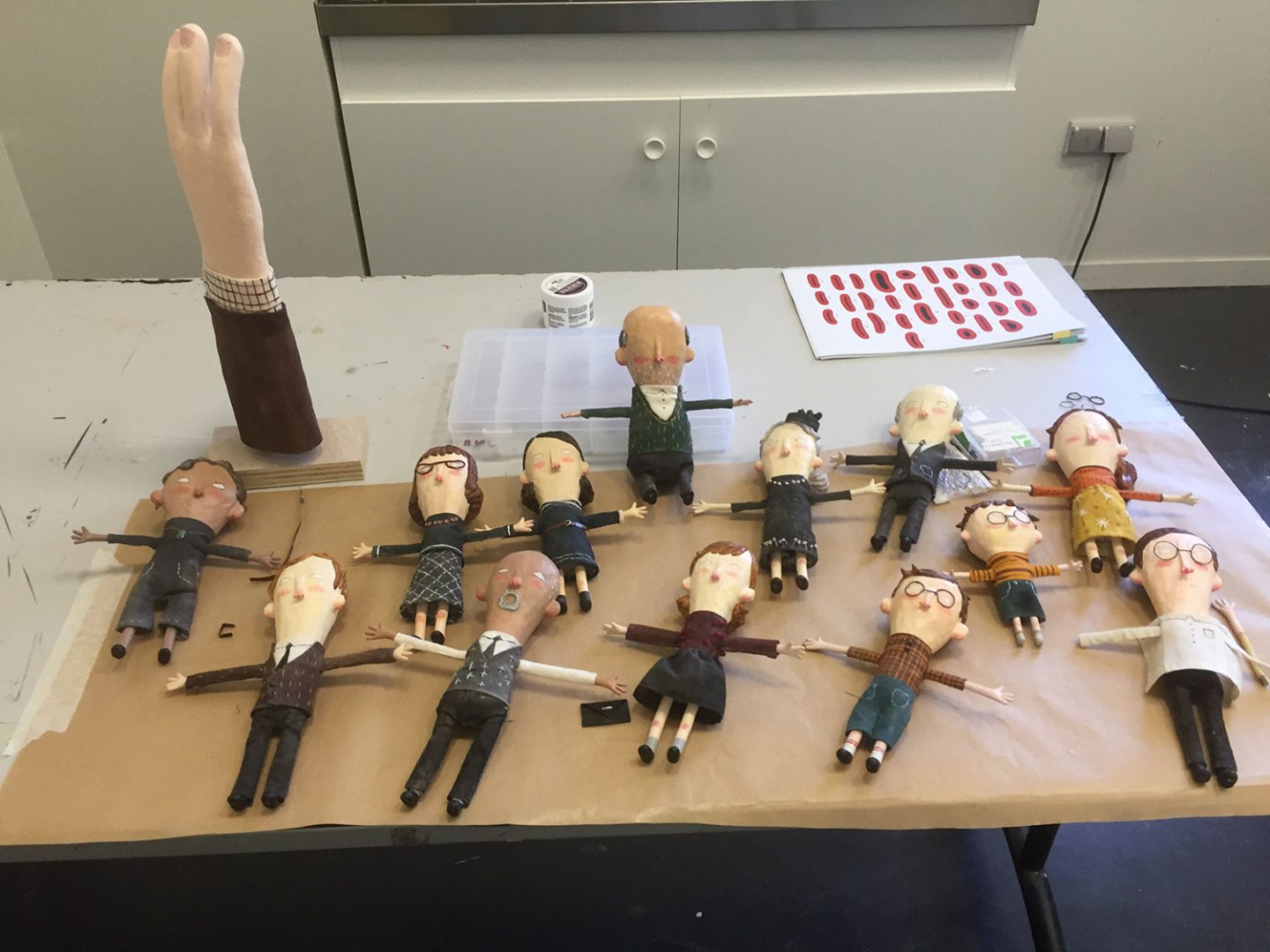

Aside from the monetary support, Kuwahata and Porter also had the help of an excellent team of artists, animators, and cinematographers.

“Our producers Nidia Santiago and Edwina Liard [of Ikki Films] were the ones who helped connect us with the artist and technicians that we worked with on the project,” says Porter. “They had a really good eye for seeing how an animator or a cinematographer might work well with our project.”

While the funding and co-production opportunities that the move to France provided were a dream come true, the perks came with a price. Kuwahata and Porter started out their stay at Ciclic, but then had to pack up shop three more times—first, to go to Ikki Films in Orbigny, then to Manuel Cam in Asnières-sur-Seine outside of Paris, and finally, back to Ciclic to fulfill the terms of their residency.

“I was so nervous to put [the main puppet] in a suitcase, so I decided to carry him with me. But then I got really nervous that he [would] look like a small skeleton going through the security system [at the airport],” laughs Kuwahata. “So we kind of went crazy disassembling every single part so we wouldn’t look so suspicious.”

Repeatedly breaking down, packing, and setting up their materials was a pain, say the directors, but their troubles didn’t end there.

Kuwahata and Porter’s previous three shorts were made using a hybrid of digital and analog techniques, says Porter, but they were adamant early on that this project be completely stop-motion. “Because of the proportions of the puppets where they have such large heads and such small feet, they couldn’t stand on their own with traditional stop-motion tie-downs,” says Porter. “We had to have a rig attached to the puppets at all times, and it caused so many issues because all those rigs had to be removed in post-production.”

Kuwahata says it was all worth it. “During, it was a headache,” she admits, “but looking back it was really quite special, because we got to experience all these different places and living situations in France.”

With a running time just short of five minutes, Negative Space manages to pack quite the punch—both emotional and visual. In one particularly captivating scene, the contents of a suitcase wash in and out of the frame like waves on a beach before engulfing the son and dragging him down to an ocean where ties and underpants swim like fish. Meticulous planning and attention to detail enabled Kuwahata and Porter to achieve a very specific emotional payout.

“When the waves come up on shore, and it’s all clothing, we had to actually put Plasticine inside the clothing so we could animate the wrinkles with control,” explains Porter. “This is a decision we made early on, which was that the clothing would be more animated and more vibrant than the people. We thought this summed up the story very well, that the people were a little bit cold, a little bit detached, but [the father and son] are able to connect through the expressiveness of what was inside the suitcase.”

Careful consideration of scale was also crucial to their vision. In several cases, they had to create multiple sets for one setting, in order to force perspective. “Often, we really put the camera close, like when the father’s picking up the little boy— we really pushed the sense that the father’s taking up a big part of his life,” says Porter.

For inspiration, Kuwahata and Porter looked to the art of Yasujiro Ozu, Ron Mueck, and Gregory Crewdson, but they avoided letting anything influence them mid-project. “I think it happens quite often in any production, maybe [you spend] seven years working on a short film, and then you keep adding things or changing things because you change,” says Kuwahata. “We tried so hard not to do that, and to stick to the original instinct, and trust our ideas at the beginning.”

Though Negative Space speaks specifically to the father-son dynamic, the Tiny Inventions team has created a piece of art that has prompted its audience, again and again, to open up about their own various familial experiences. “Probably the best part of what happened after finishing the film is that people would come up to us and start telling us about their relationship with their parents. You’re telling me your darkest, deepest secret,” says Kuwahata. “It’s interesting that people feel comfortable to share their stories with us.”

.png)