Interview: Richard Williams Talks About His Oscar and BAFTA-Nominated Short ‘Prologue’

In a career rich with achievements and honors, the beginning of 2016 might rank up there as one of Richard Williams’ more glorious moments. His short film Prologue, over twelve years in the making, was nominated for both an Oscar and a BAFTA, the English equivalent to the Academy Awards, in the span of seven days.

To put that into some kind of perspective, the last time Williams won a short film Oscar was 43 years ago, when his half-hour adaptation of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol was honored by the Academy. But that’s nothing compared to the short film BAFTA honor, which he last won over a half-century ago for his inventive wandering into philosophical terrain, The Little Island.

One reason for the stretch of time in between nominations is that Williams hasn’t always made shorts. For decades, he ran one of the most storied commercial houses in animation history, Richard Williams Animation, and then directed features, including the animation in the contemporary classic Who Framed Roger Rabbit, which was duly recognized by both the Oscars and BAFTAs for its marriage of art and technology.

Another reason for the slow filmmaking pace is Williams has a difficult employer. “I work for this terribly demanding boss, which is me, and the bastard wants it right,” he explained. ” I’ve only just gotten to the point where I could marry my draftsmanship to the animation knowledge. It’s always been a battle for me.”

Prologue is appropriately titled; it is the first part of a feature film loosely based on Aristophanes’ anti-war play “Lysisrata,” in which Greek women withhold sexual privileges from their warring husbands until they stop killing each other. The 2,400-year-old play also served as the basis for Spike Lee’s politically charged Chi-Raq, but Williams’ interest in the ever-timely tale was more carnal in nature.

He discovered the play as a teenager when he found a copy of it lying around the house. It was an edition illustrated by Norman Lindsay, and the Australian artist’s comical drawings of voluptuous women baring all left an impression on the teenaged Williams. “Lindsay would have been a marvelous animator,” Williams says. “There’s humor in everything he draws. He drew these very attractive women but they’re funny.”

Throughout his career, Williams occasionally entertained the idea of animating the story. “I thought, ‘God, I wonder if I’ll ever get good enough?’ I’m not good enough to do this.’ When I finally got good enough to think about it, it was after Roger Rabbit.”

The alternate title to the film, Williams likes to say, is Will I live to finish it? But finishing a 90-minute film does not seem to be the priority so much as creating something exactly the way he envisions it. After a career spent working in everyone else’s style but his own, and designing projects that could survive his studio’s production pipeline, Williams is finally making something purely for his own enjoyment — and to the singular standard that no crew under him could ever hope to attain. As a result, Prologue, he says, is “the only thing so far in my career that I’ve ever been really been pleased with, that I was able to succeed with what I was trying to do in all the different aspects.”

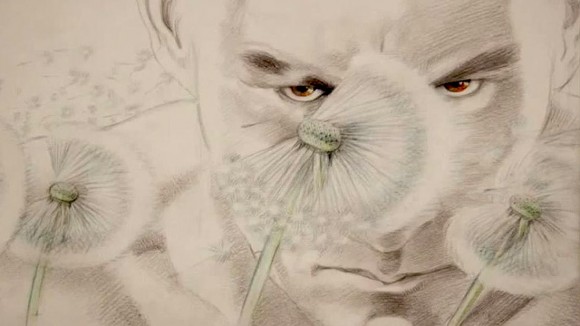

To ensure that everything comes out exactly as he intends, Williams even shoots the drawings under camera himself. Digital technology enters the picture only during the compositing when dust and fingerprints are taken off his drawings, and images are sharpened and graded. The rest of the production is as technically primitive as when Winsor McCay made Gertie the Dinosaur a full century ago. “I’m going back to 1900 and just drawing on one sheet of paper. It’s a tremendous relief: no cels, virtually no camera. If you can’t get it on one sheet of paper, it doesn’t go in.”

The self-imposed dictum to create each frame on a single sheet of paper means that all of the film’s considerable technical complexity emanates from the tip of Williams’s pencil. For example, he can’t pan across a background because there aren’t traditional backgrounds. To indicate space, he’ll add some grass or draw a few birds into a shot, or he’ll pan along an object a character is holding, like a spear. “I found that it’s like radio,” he explains. “You’re imagining things because it’s not quite all there.”

He also tries to avoid cuts in the film, a Williams trademark that has been employed to breathtaking effect in earlier projects, like his visionary but never-quite-completed Thief and the Cobbler. “We should have control over the medium,” he says simply.

So, what’s the secret, I asked him, to staying sharp as a draftsman in his ninth decade? Life drawing, he says. “It’s the hardest thing you can do. When you get out of it for six months and you go back in, you realize you’re a bum. That’s why people don’t go back to it. They say, ‘Oh, I did that in art school. We don’t do that anymore.’ And then you get stuck with cartoons.”

Williams, who keeps a studio space in another storied English animation outfit, Aardman Animations, is more than halfway done with the follow-up to Prologue, or the next sequence of his “Lysistrata” adaptation. The new film will finally introduce the Lindsay-inspired ladies that so many decades ago served as the original spark for the project.

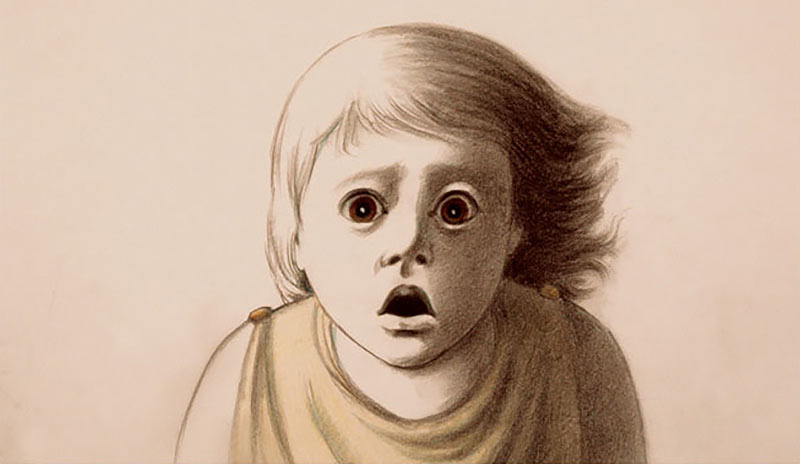

He works happily in total freedom, having to contend only with his own demanding standards — and those of his family members. About a decade ago, when he had started animating on Prologue, he asked his youngest son, then ten-years-old, what he thought of the drawings. “Well, the better artists manage to maintain consistency in the faces,” his son replied.

“He was right,” Williams admitted. “They changed a little bit if you want to be critical.”