How Jon Klassen Leapt from Animation to Children’s Books

Welcome to a new column by Chris Arrant who is also the editor of CB Biz. In today’s inaugural column, he profiles artist Jon Klassen:

Jon Klassen might have made his first big splash as an animator, but in recent years he’s followed the path of animators like Mo Willems and Tony Fucile and applied his illustrative talents toward the picture book medium. After working as a concept artist and illustrator on films like Coraline and Kung Fu Panda 2, the Los Angeles-based artist is focusing the majority of his time on his burgeoning bibliography of illustrated children’s storybooks like Cats’ Night Out and The Incorrigible Children of Ashton Place series.

Klassen tells Cartoon Brew that making the leap to children’s book wasn’t as dramatic as it might have been in years past. “It’s pretty fantastic,” he said. “The tools to make illustration or film are merging closer together, and the more you jump back and forth, the more you see how they overlap even at the conceptual stage. I think that illustrators are finding themselves trying out more animation than they would’ve before, and people who are in animation are trying out more print stuff. Hopefully it leads to a lot of fresh work.”

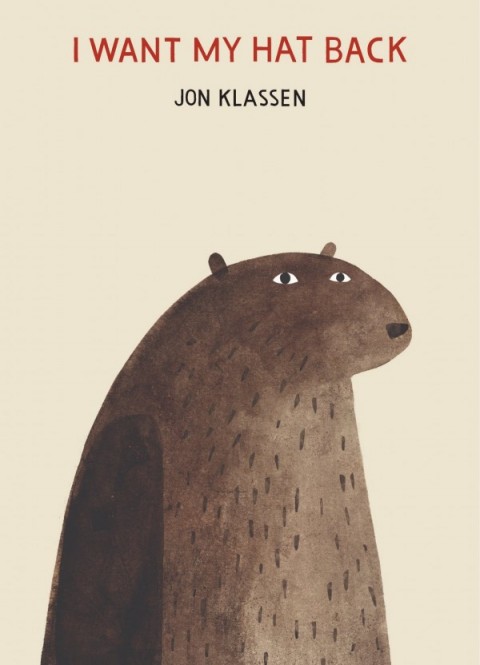

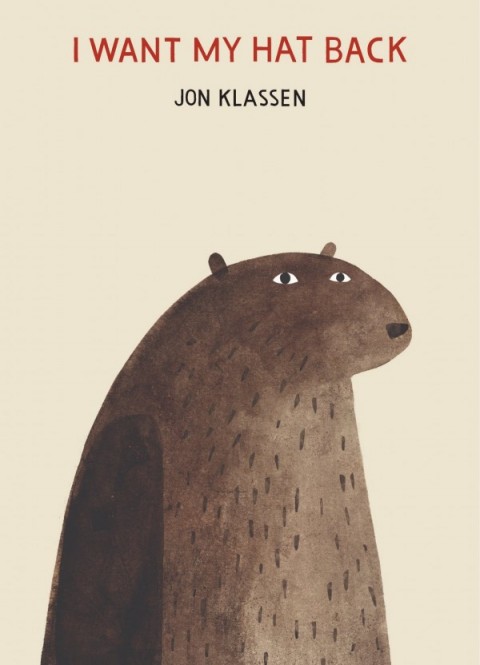

Klassen has illustrated a number of print picture books over the years, but it’s his most recent, I Want My Hat Back, that holds a special place for him because it’s the first he wrote himself. Released in September by Candlewick Press, it was chosen a couple weeks ago as one of The New York Times Book Review’s Ten Best Illustrated Books of the Year.

“I’d never written anything for real before, and the formality of writing was really making me nervous, so it was a relief to try everything in dialog instead of narration,” Klassen explained. “The stiffness of everything in the book comes from my nervousness about the idea of trying a book, but it was fun to use that in the story itself. Also I wanted to do something that looked simple, and when you’re illustrating something for somebody else you get nervous about submitting something too simple for fear it’ll look lazy, so it was nice to give myself the excuse. The story really happened on its own once the tone was set. I got lucky there.”

“I’d never written anything for real before, and the formality of writing was really making me nervous, so it was a relief to try everything in dialog instead of narration,” Klassen explained. “The stiffness of everything in the book comes from my nervousness about the idea of trying a book, but it was fun to use that in the story itself. Also I wanted to do something that looked simple, and when you’re illustrating something for somebody else you get nervous about submitting something too simple for fear it’ll look lazy, so it was nice to give myself the excuse. The story really happened on its own once the tone was set. I got lucky there.”

Although picture books might seem like a long way from animation, the list of animators who have moonlighted as picture book illustrators is a who’s who of animation history: Tom McKimson, Pete Alvarado, Hawley Pratt, Al Dempster, Tony Rizzo, Eyvind Earle, Mary Blair, Paul Julian, Bob Dranko, Chris Jenkyns, and Campbell Grant, to name just a few Golden Age artists. Klassen came to work in picture books as an adult after realizing how much they influenced his early stabs at animation.

“After I got into the design and illustration end of animation, I realized how big a deal those books were and are to me. The amount of mood you remember from even pretty simple books is so cool,” he said. “I’ve wanted to do books since the beginning, probably, but it’s one of those things you sort of feel like you need to get invited to do.”

In a break from his drawing board, Klassen teaches a class at CalArts on Wednesdays titled Illustration for Animation, and he readily admitted that “it’s as vague as it sounds.”

“I’ve never taught a class before so I’m feeling my way through it,” Klassen said, “but mainly I’m trying to get them to think past the fact that they are already pretty good at drawing things and get into the reasons why they are drawing what they are drawing. They’re doing so much work on their own, technically they’re always going to get better anyway, so I’m trying to work on thinking about their approach before the drawing starts. That can be useful in all sorts of different jobs.”

Klassen’s own student animation, “An Eye For An Annai,” created with Dan Rodrigues during their third year at Sheridan College’s Classical Animation Program.

Speaking of different jobs, picture books aren’t the only place you’ll find Klassen’s work. He’s also contributed editorial illustrations to a number of newspapers and magazines, including a recent piece for The New York Times. Although he says picture books were initially his primary goal, he enjoys the unique nature of creating editorial illustrations.

“Smaller scale jobs like that, when they come along and when the schedule suits, are really fun because the turnaround is so quick,” Klassen said. “With a book you have to wait around a year between finishing it and showing it to people, and with editorial work you finish it on Thursday and it’s out on Sunday. I’m not sure it’s what I’m best at, but it’s nice when you get asked to do it.”

Cover illustration for the “New York Times Book Review,” focused on a review of “The Grief of Others” by Leah Hager Cohen.

Cover illustration for the “New York Times Book Review,” focused on a review of “The Grief of Others” by Leah Hager Cohen.

One thing that Klassen is always asked by admirers of his work is when and where he’ll show up next in animation. Although his main focus remains on books nowadays, animation is finding a way back into his life. “I do try to keep a toe in animation, though mostly on smaller scale stuff,” he said. “With the hardware that’s out there now, book publishers are looking harder at developing stories digitally. I think one of the things they’re looking for is kind of a replacement for a page turn, something to move the story from point to point at your own pace, but without making so interactive that you stop feeling like you’re being told a story in a controlled way.”

“One of the big differences between books and animation or film in general is that with books you can play with the idea that the viewer is moving at their own speed through the story, whereas with film you are controlling their time,” he said. “There are advantages to both, but if you could bring some of what is fun about moving through the kind of space a film creates into the experience of reading a story at your own pace, it could be a really nice middle ground. It could also be really lame. I guess we’ll see.” Chances are if Klassen’s involved, it’ll be something worth our time.

Concept art for “Coraline.”