How Andrew Coats and Lou Hamou-Lhadj Made The Independent Short ‘Borrowed Time’ Inside Pixar

Making an independent animated short is hard. But what if you had the power of Pixar’s animation toolset and renderfarm behind you?

That’s exactly what directors Andrew Coats and Lou Hamou-Lhadj were able to leverage for their short Borrowed Time, about a sheriff whose memories of a tragic event keep haunting him. The short has been racking up accolades on the festival circuit, scoring Oscar-qualifying wins at the St. Louis and Nashville film festivals, and again this week, winning best in show at the SIGGRAPH Computer Animation Festival.

Cartoon Brew caught up with the directors at SIGGRAPH to discuss how they made an independent short inside of Pixar, and how doing so helped—and sometimes hindered—production.

What, you can make a non-Pixar film at Pixar?

Borrowed Time was made possible via Pixar’s Co-op Program, part of the company’s internal Pixar University professional development program. Employees can apply and if successful are then allowed to use, in their own time, the Pixar pipeline at work. Interestingly, Borrowed Time was the first CG film to be accepted; most of the Co-op productions so far have been live action.

That presented one of the first challenges for the directors, since other filmmakers had traditionally just used live action equipment available at the studio and not necessarily employed the full animation workflow. “There were a lot of technical hurdles,” said Coats, who is an animator at Pixar. “There’s a team of people who are usually on one of our movies that we really didn’t have available to help on our team. So we had to build everything.”

Building a pipeline for the short was also a challenge in an environment where Pixar’s technology was constantly changing, a prospect made somewhat more difficult as Borrowed Time took five years to make. That meant a workflow the directors could follow based on what Pixar was doing, say on Monsters University would change once things switched over to Inside Out—the pipeline for Borrowed Time changed three times over the five years to be in parity with Pixar’s films.

Perhaps the hardest part of these pipeline issues was that Coats and Hamou-Lhadj, who is a character artist, were at the front end of most Pixar productions, meaning they didn’t have direct experience with other stages of the process such as lighting. So they had to learn, or coax other artists at Pixar to help them (only Pixar-based employees could be involved in the film production that occurred at the studio). Other artists pitched in on the short after hours, during lunch breaks, and on weekends.

Being able to use the technology and the renderfarm was of course a huge benefit, but it did not mean the directors had free reign. “We needed to make sure we didn’t conflict with anything that was ongoing at Pixar,” explained Hamou-Lhadj. “So of the 30,000 slots on the farm, say, we had 100. Still, who could get something like that at home?”

Discovering The Story

Coats and Hamou-Lhadj embarked on a years-long process of story development before they had actually joined Pixar. The idea to make a short all began when they were still in school together. After graduating from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, the artists had jobs in separate locations—at Pixar (Hamou-Lhadj) and Blue Sky Studios (Coats). But it was not until Coats moved to Pixar in 2010 that things ramped up on what would become Borrowed Time.

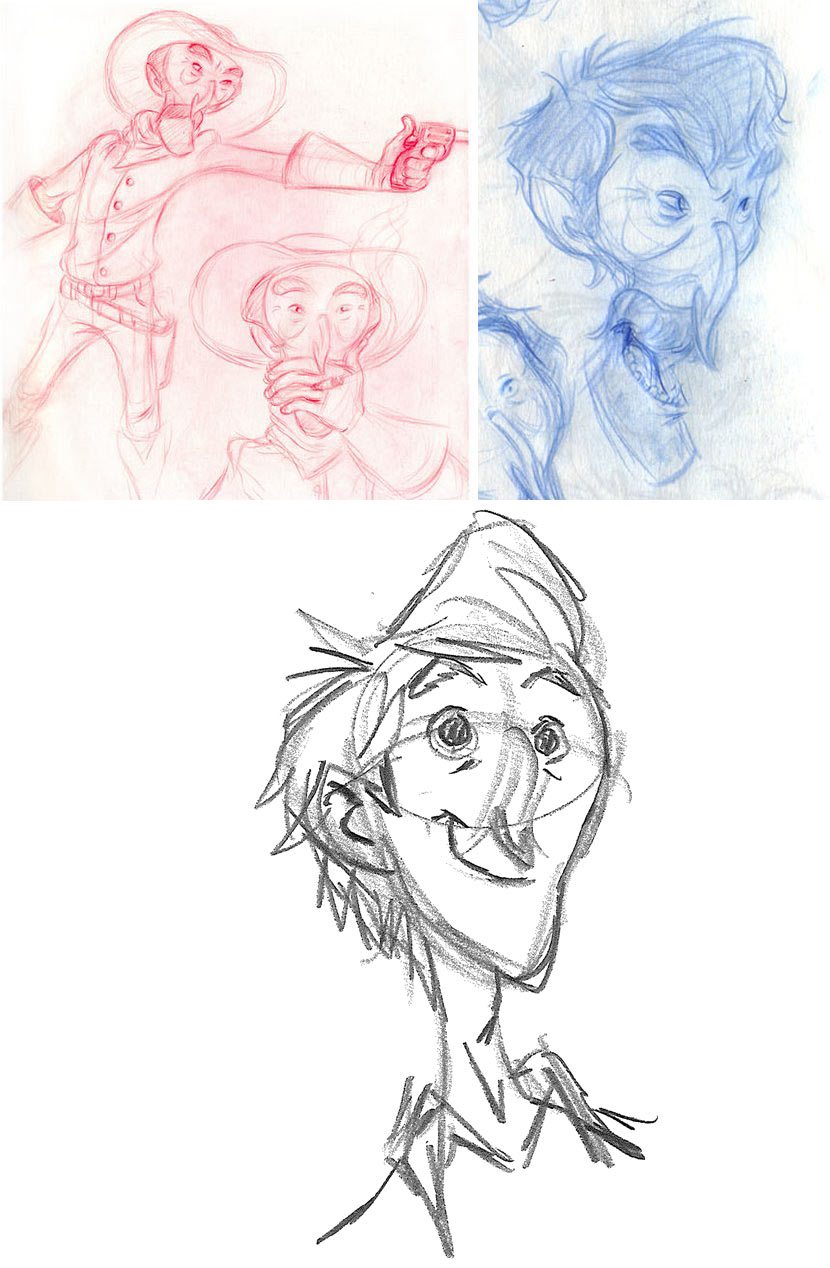

One of the earlier ideas the pair had been playing around with was a Western-type story. At that stage, the plan had been to develop what Coats describes as a “Gobelins-like short which was action based and fun and frenetic.” Soon they realized they weren’t satisfied with the story they were telling, with Hamou-Lhadj noting that “if it was going to take us this long to do something, there might as well be a little more substance to it.”

Aiming for a short under ten minutes (the final cut is just shy of seven), the directors went through numerous iterations of their sheriff story. They had, for example, many additional characters, aimed at setting up moments of betrayal around the main sheriff before settling on a main theme of forgiveness. There was also an additional three to four minute long heist scene which they cut down after recognizing that it was mostly action and not serving the story.

Carrying out those story cuts was one of the big learning curves on the production, both directors mentioned to Cartoon Brew. But sometimes this was devastating, such as when one of their major characters, an old man, was conceptualized, modeled, rigged, groomed, and textured – but then removed from the film. Part of the issue was that those steps had been taken perhaps earlier than normal in the process, meaning, says Coats, “it affected our decision to cut him because we had put so much time into him. The decision to take him out was heartbreaking.”

The Final Push To Completion

Another take-away on the production for the directors was working out how much time to spend on it. They admit some weeks they would be at work until early morning hours, and not have a clear sense of all the steps still required. That was, until they brought on producer Amanda Deering Jones, a script supervisor at Pixar, whom they credit with getting Borrowed Time back on track. “She’s so good at what she does and we’re so bad at it,” joked Hamou-Lhadj.

Jones was crucial in making the score and sound mix possible, too. She contacted composer Gustavo Santaolalla (Brokeback Mountain, Babel, The Last of Us) and had a connection with Skywalker Sound for the final sound design. And, the directors say, Jones was very savvy about the concept of ‘temp love’ in the temporary lay-downs they had established in animatics. Hamou-Lhadj, for instance, admits to gravitating too closely to the temp tracks from The Last of Us they had used before hearing Santaolalla’s original music for the short.

Right now, Coats and Hamou-Lhadj have been chaperoning the film at various film festivals and discussed the work earlier this week at SIGGRAPH. Asked whether this story or another might be the set-up for a feature-length version, the directors say it is still too early to tell. “We would love to make a feature,” said Coats, “but we don’t know what the reality is for really doing that, especially with the budgets required to make these kinds of films. We’ve had five years of our time in this world so right at the moment we’re itching to do something new and different.”