6 Stories of Cartoonists Who Stood Against Tyranny

In light of yesterday’s horrific attack in Paris on the editors and staff of the satirical publication Charlie Hebdo, we thought it would be good to remember that the fight for freedom of expression has been a long and ongoing struggle—and the humble cartoonist has often found himself at the center of that struggle.

Throughout history and around the world, cartoonists have had their work banned and protested against, and have personally been intimidated, jailed, and murdered. Today we look at six such stories, from hundreds of possibilities, that show how cartoonists and illustrators have taken memorable stands against intimidation and tyranny.

Let us not forget that while cartoons can be silly and fun, they also remain one of our most effective weapons for exposing and confronting the forces of oppression and the structures of power that dominate our lives. The cartoonist is a powerful individual, and after yesterday, they are more powerful than ever. We must use the power wisely.

1. Honore Daumier and Charles Philipon

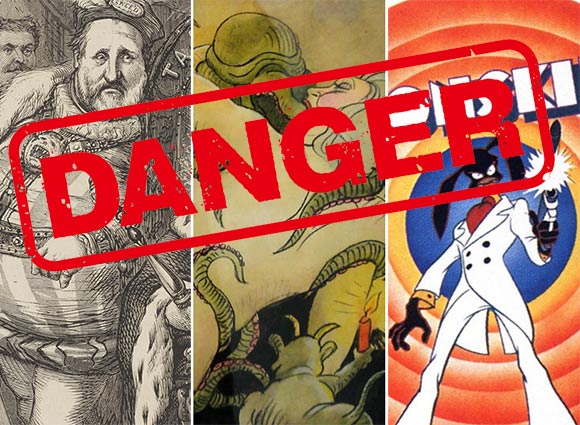

Daumier (1808-1879) found early fame from an 1831 drawing that the public almost didn’t see: “Gargantua,” a portrait of French King Louis-Philippe as a giant, swallowing bags of money brought him by minuscule servants. The King was exorbitantly wealthy, in part due to his “salary” of over 18 million francs annually, plus upkeep for his castles and palaces, much of this from taxes and levies on the poor. Daumier’s satire was to have been published in the magazine La Caricature, but the authorities put a stop to that.

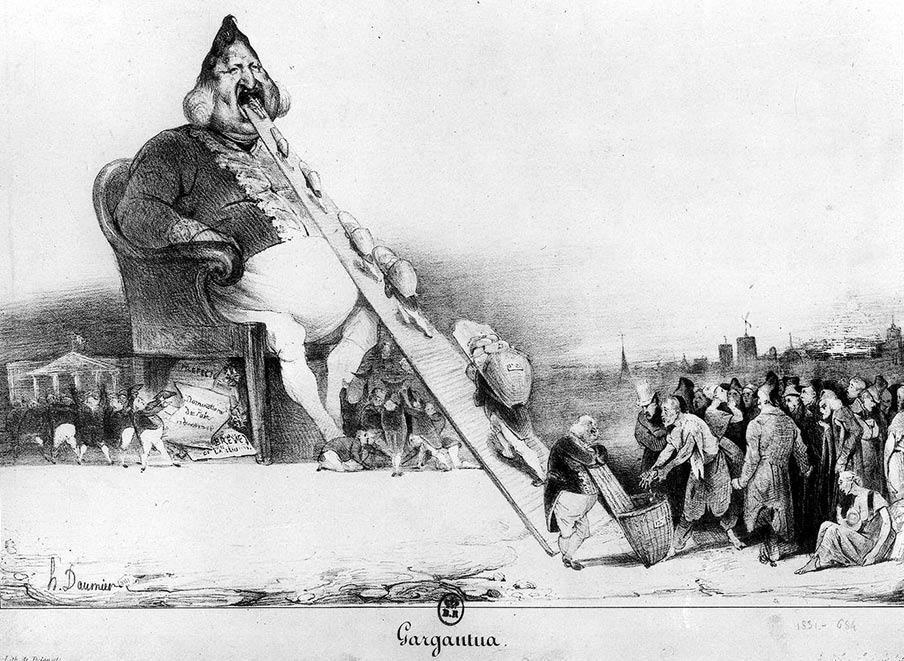

Daumier was not alone. His editor, Charles Philipon (1800-1861), was also accused of insulting the King in the same indictment, thanks to his extended campaign to rebrand Louis-Philippe as a piece of fruit, specifically a pear. An article in La Caricature ridiculing the court’s decision to censor “Gargantua” was enough to force Daumier, Philipon (1800-1861), and Philipon’s brother-in-law, Gabriel Aubert, to stand trial.

In court Philipon demonstrated the art of caricature by presenting a series of drawings that blurred the line between Louis-Philippe and a pear. He implored the court to indict his drawing of a Burgundy pear along with his pear-inspired drawings of the King: “You cannot acquit this sketch either, for it certainly resembles the other three.” This bit of bravado was quickly picked up in the streets, and the pear became a common element in satirical drawing of the time (the Streisand effect might be more accurately called the Philipon effect). However, the enhanced publicity did not help Philipon or his associates, who were sentenced to six months in jail, a 500 franc fine, plus legal fees and expenses. Philipon and Daumier were undaunted, and once free, quickly returned to work on a new magazine, Le Charivari, and greater success.

2. Thomas Nast

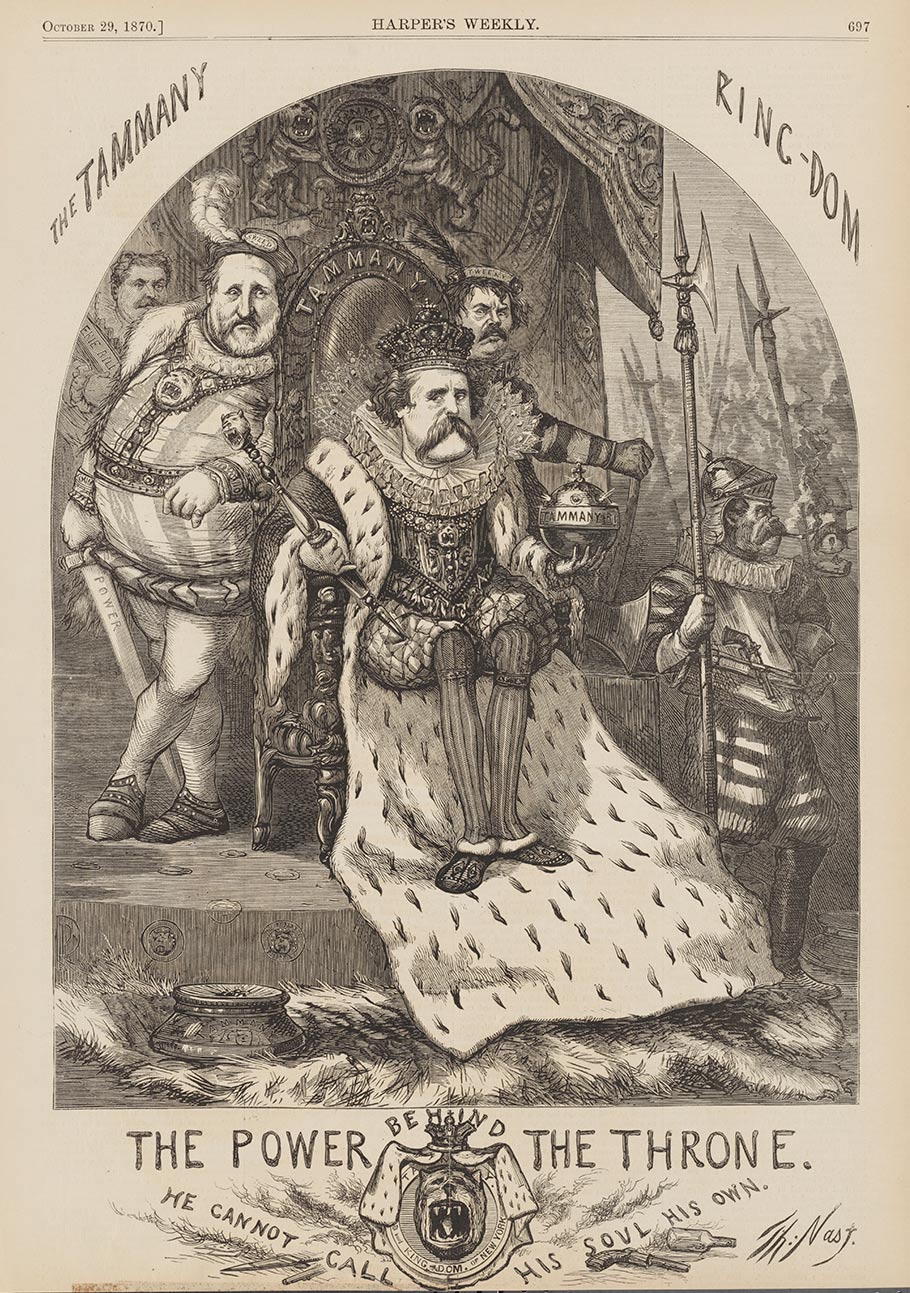

William “Boss” Tweed and his associates gained total power over the government of New York City in the late 1860s, and ran it to profit themselves and their cronies. Tweed’s influence spread from Tammany Hall, the political society that dominated New York politics for decades, right up to the State Legislature. Tweed’s nemesis was cartoonist Thomas Nast (1840-1902), whose cartoons attacking corruption appeared regularly in the pages of Harper’s Weekly.

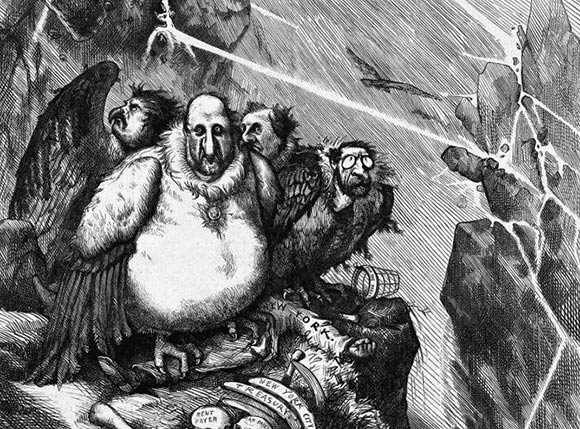

The German-born immigrant Nast portrayed Tweed as a bloated, thuggish figure, in one instance with a bag of money for a head; in another, huddled with his cronies as vultures waiting out a storm. Nast’s cartoons were especially effective at reaching Tweed’s power base of Irish immigrants who were often illiterate. “Let’s stop them damned pictures,” Tweed was reported to have said. “I don’t care so much what the papers write about me—my constituents can’t read—but damned they can see the pictures.”

Tweed once sent a man to Nast offering him a bribe of $100,000, a “gift” that would allow Nast to go to Europe and further his artistic studies. Nast managed to bargain his way up to $500,000 (nearly $9 million in today’s dollars) before turning the offer down flat. Tweed’s men were unseated in the 1871 elections, in large part due to Nast’s biting portrayals.

After Tweed fled the country in 1875, he was arrested in Spain, where the authorities used Nast’s cartoons to help identify him. Tweed thus became the second most recognizable figure in Nast’s repertoire, right after Nast’s depictions of Santa Claus, which have remained iconic to this day.

3. Tomi Ungerer

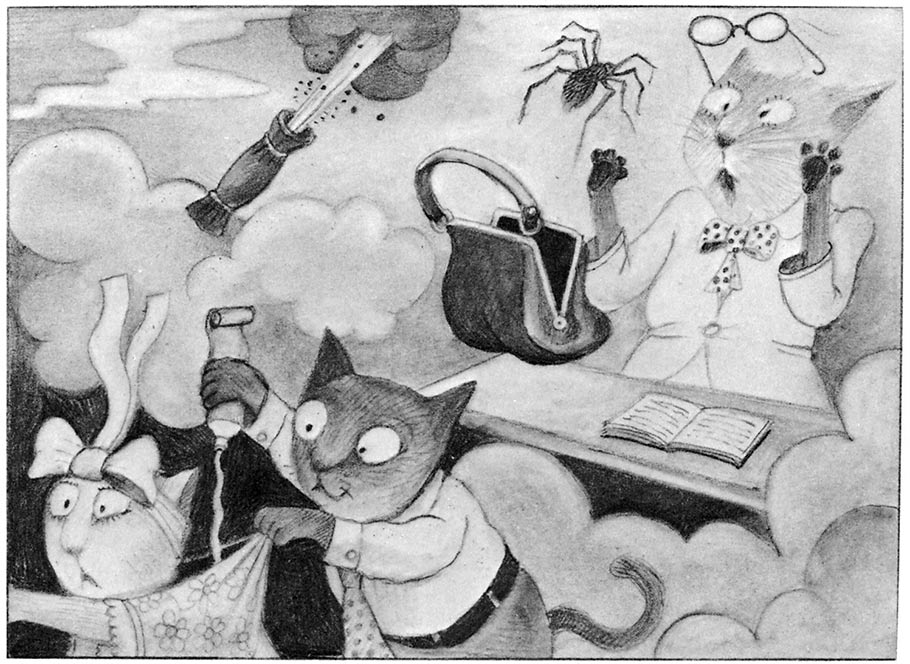

Among other accomplishments as a graphic artist, Jean-Thomas “Tomi” Ungerer (b. 1931) has written and illustrated dozens of children’s classics including The Three Robbers, Moon Man and The Mellops series. His distinctive wit, imaginative prose, and brilliant drawings have made him the subject of much admiration and some controversy. Not content with just producing children’s books, he began drawing albums of erotica, which made him suspect in the eyes of some parents and school boards.

Can you trust a book full of cute, if disobedient, cats (No Kiss for Mama, 1973) if the artist also draws women in bondage gear (Fornicon, 1969)? Subtle yet pointed political commentary could also be found in the backgrounds of some of his children’s book drawings. His desire to draw as he pleased led to an unofficial ban on his books, and publishers allowed his titles to go out of print. Ungerer went into exile in Nova Scotia, Canada, and didn’t do another children’s book for nearly twenty-five years, though he continued to create illustrations for adults.

The children’s publishing industry finally gave in, and Ungerer’s “ban” was lifted in 1998 when he won the Hans Christian Andersen Medal for his children’s book illustrations, an acknowledgement that an artist does not have to be pigeonholed into creating artwork just for children. Today, Phaidon has brought many of Ungerer’s children’s books back into print, and Ungerer was the subject of a 2011 retrospective at the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, Massachusetts.

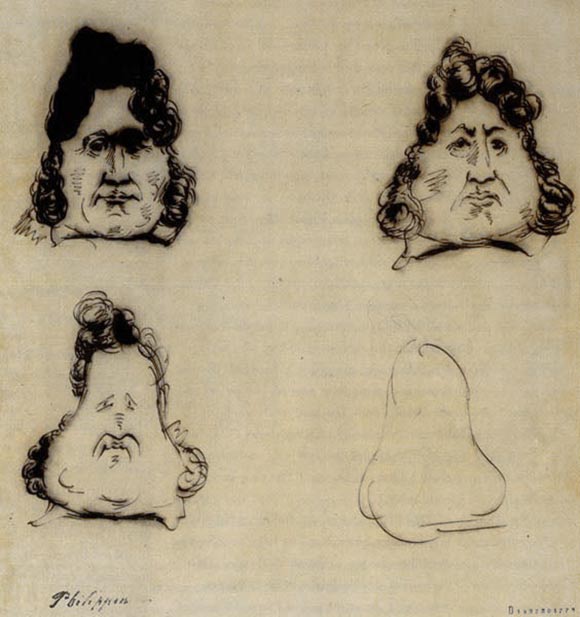

4. Ralph Bakshi

Say what you will about the films of Ralph Bakshi (born 1938), but he has always done his best to stand by his principles. His 1975 film Coonskin was intended as an acid send-up of racial stereotypes, taking names and ideas from Uncle Remus stories, blackface minstrelsy, and other ethnic stereotypes. He hired African-American animators and actors (the film is part live-action, part-animation), and wrote the lyrics to the title song, set to music by Scatman Crothers.

Many critics did not get the satire, including the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE), though no CORE member had seen the film. A screening was arranged at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan. The scene, according to various witnesses, was chaotic. Some protesters got in and marched up and down the aisles. At the event, Bakshi asked Al Sharpton why he didn’t watch the film, and Sharpton retorted, “I don’t got to see shit; I can smell shit!” The greatest disruption was to the planned post-screening talk by Bakshi himself, which had to be cut short. The controversy surrounding its content hastened Paramount Pictures’s decision to drop the film from its releease schedule; the short-lived Bryanston Distributing Company picked up the title and made a modest effort to distribute it in theaters.

Coonskin has since been released on DVD and Blu-Ray, and has been praised by Spike Lee, Quentin Tarantino, and Wu-Tang Clan, among others. Rumors of a proposed sequel surface periodically. Bakshi has said he considers it his best film, and he might yet be proven right.

5. Naji Salim al-Ali

At one time Naji Salim al-Ali (1938-1987) was one of the best-known cartoonists in the Palestinian world. He drew cartoons critical of the Israeli occupation, insisting on the right of his people to all of historic Palestine, and other cartoons that were harshly critical of Palestinian leaders. He drew cartoons for newspapers in Kuwait, and while living there was often detained by police and had his work censored. After finally being expelled from Kuwait, he moved to London. In 1979 he was elected President of the League of Arab Cartoonists.

His best-known character, Handhala, is a symbolic representation of the Palestinian people, a boy about ten years old, barefoot and wearing ragged clothes. Starting in 1973 Handhala has his back turned to the viewer, his hands clasped behind him indicative of rejecting outside solutions to the Palestinian plight. This figure has more recently been used by the Iranian Green Movement.

Al-Ali was walking outside the London office of the Kuwaiti newspaper Al Qabas on July 22, 1987, when he was shot point-blank in the middle of the street. He died five weeks later without regaining consciousness. Two suspects were arrested, both of whom admitted to being double agents, working ostensibly for the Yasser Arafat’s Palestine Liberation Organization while also working for Mossad, the Israeli intelligence organization.

It remains unclear which organization ordered Naji al-Ali’s death; he had made enemies on both sides. Several books of his works have been published, and his life was made into a movie in 1992 starring Egyptian actor Noor El-Sherif. In the end his art survives, whether you agree with his opinions or not. That victory is one we can hold onto.

6. Trey Parker and Matt Stone

South Park creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone began their collaboration with a pair of animated shorts now known as “Jesus vs. Frosty” and “Jesus vs. Santa” (aka The Spirit of Christmas.) launching a still ongoing career of equal-opportunity offending. In some ways, South Park is a descendant of Coonskin, using every existing stereotype (and creating new ones) to satiric and educational effect, but on a far wider scope. Depictions of Jesus and the Virgin Mary have drawn repeated protests from Christian groups; the Church of Scientology was also lampooned, causing cast member Isaac Hayes, a Scientologist, to depart the show.

A two-part episode in season 10, “Cartoon Wars,” dealt with the possible repercussions of depicting the Prophet Muhammad on TV, only to have that depiction censored by Comedy Central. A later attempt to show Muhammad met with the same censorship, and death threats from an obscure radical Muslim group. No one noticed that Muhammad appeared, in a positive light, in an earlier episode, “Super Best Friends,” until much later, whereupon that episode was censored or removed from streaming platforms and home video releases. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints objected to South Park’s depiction of Mormonism: Parker and Stone carried on (with composer/lyricist Robert Lopez) to create the Broadway musical The Book of Mormon, which won nine Tony Awards.

These complaints against the show barely scratch the surface. South Park has a charmed existence, a sort of TV Teflon that keeps scandal from sticking. Very few of the many calls for boycotts and censorship have had any effect. Schools may ban South Park-related clothing, and advocacy groups call for the show’s cancellation, but it soldiers on, garnering Emmys and a Peabody Award along the way. Its use of profanity and gleeful depictions of pretty much any sort of amorality you can think of have made it unique on television. It can be crude, cringe-inducing, uproariously funny, and honest to a degree other animated shows dare not approach.