‘A Monster Calls’ Used Every Kind of Animation To Tell Its Story

Using animation to tell a story within a story is a challenging prospect in a live action film. There are many recent successful examples, such as The Tale of the Three Brothers directed by Ben Hibon in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 1 or O-Ren Ishii’s backstory told in anime form by Kazuto Nakazawa in Kill Bill: Volume 1. The latest film to feature animated sequences is J.A. Bayona’s A Monster Calls, based on the novel by Patrick Ness, who also wrote the screenplay.

The film, already a big hit in Spain and opening wide in the United States today, is heavy in animation. The central character is a giant cg yew tree—animated by MPC—which comes to tell Conor O’Malley (Lewis MacDougall) four stories while the young boy is dealing with the terminal illness of his mother. The tales inside the film, often ink-like and painterly in nature, were directed by Headless Studio’s Adrian Garcia and realized by Glassworks Barcelona.

Cartoon Brew goes behind the scenes on the stories with Glassworks’ head of 3D Javier Verdugo, who helped orchestrate specific painterly looks with a broad mix of graphics and 3D software, and a variety of techniques ranging from real ink reference, 3D animation, and effects simulation tools.

Cartoon Brew: How did Glassworks Barcelona get the job to work on A Monster Calls?

Javier Verdugo: It began because I am a good friend of Adrian Garcia from Headless. They showed us the project, the concept, and we saw the context, and they were amazing and so we said, “Okay we need to do it.” There was something there that was going to be really different.

At what stage of production were these sequences when they came to you? Had they already created concepts?

Javier Verdugo: Yes, they already had storyboards. And they had done character designs, and concepts for different scenes as well as color concepts. They actually worked for a whole year before coming to us. And then once we started working on it, Headless were still the directors of the tales, and we would have constant reviews as we kept going.

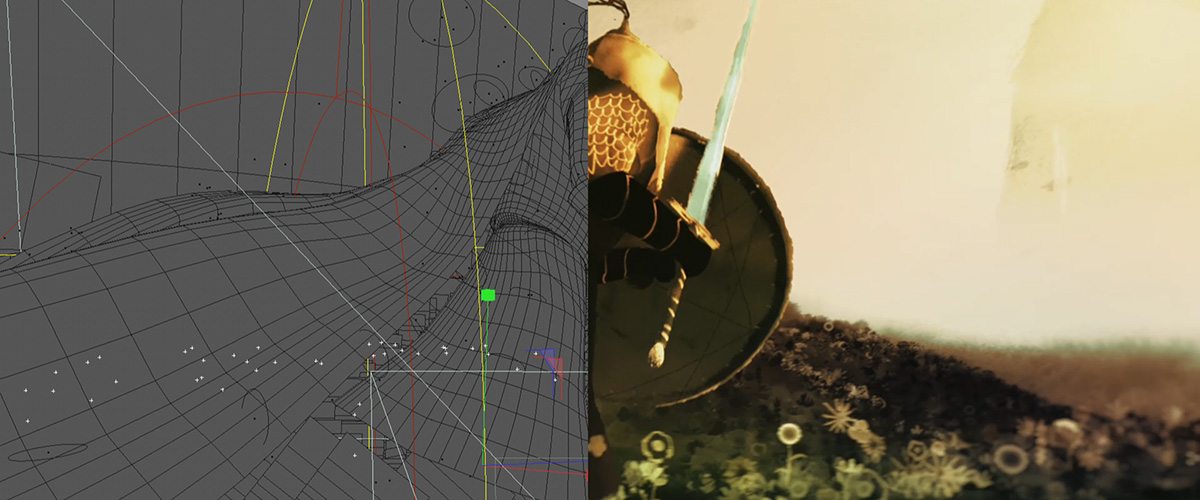

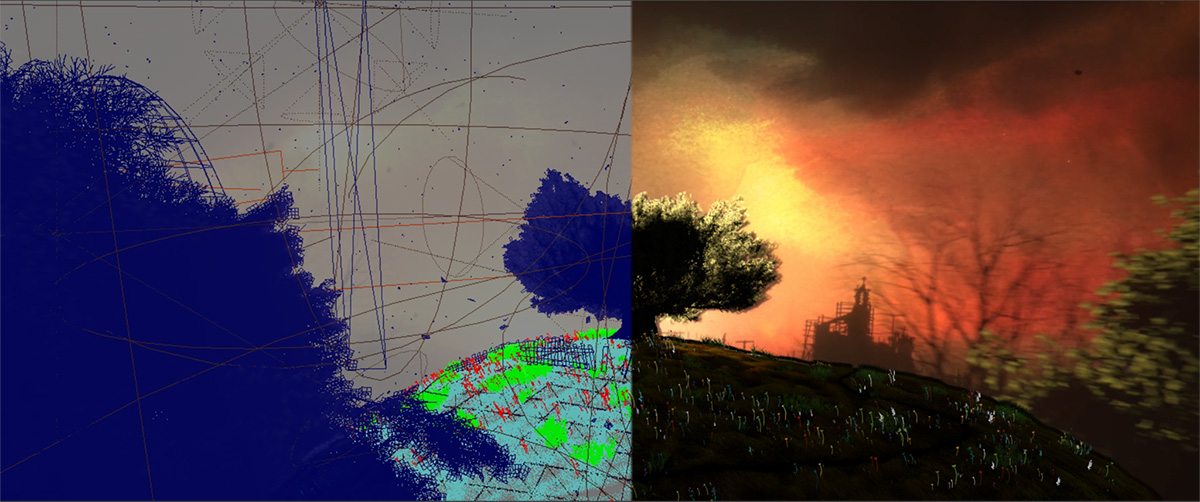

What were some of your specific design challenges – because clearly these have a 2D graphic look, but they seem to have been achieved with 3D animation?

Javier Verdugo: That was the most difficult part of the project because we wanted to have a 2D look. The sequences needed to be like the drawing of a child, in terms of the paintings Conor does during the movie. But the director also wanted to move the camera in certain ways and rotate around objects. So that was a really big challenge because to do a 2D look with a camera that’s always moving is quite a difficult process.

To do that strictly in 2D you have to make many layers in 2D, and have specific ways of projecting the textures in compositing. And we tried – we were doing tests for almost half a year. But in the end, we said, okay this is not working.

How did you then settle on the final technical approach?

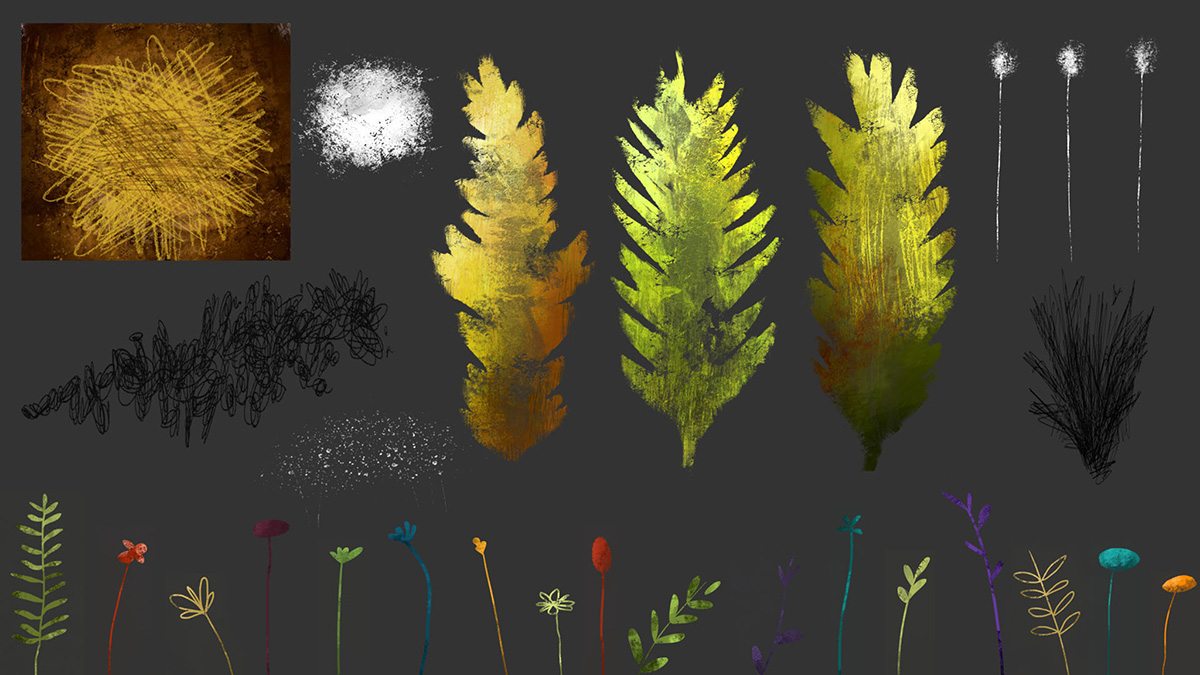

Javier Verdugo: We started by actually shooting various ink layers, and we projected these as 2D planes inside of 3D scenes, and then we just had many, many layers in the final renders. We were also painting all the textures by hand, which made everything look like it was made by hand. And then at the end of the process when we were compositing everything in After Effects, and the director had approved all the camera movement and the animatic, we did some painting frame-by-frame on top of the final composites.

It was like a big loop of 2D because we were already making things in 2D by hand painting frame-by-frame. It was a really hard job because we were frame-by-frame painting say some flags, then painting something for the clothes, and even painting the hair of the horse by hand. But that was helping to break the 3D look a lot. Working frame-by-frame was the most important part.

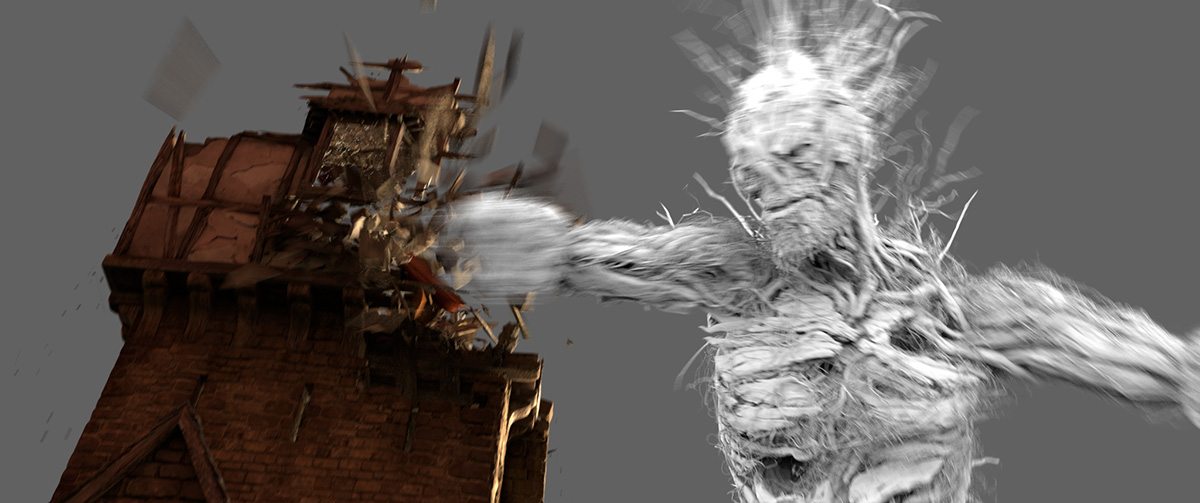

One of the animated sequences is a combination of live action of the boy and animation of the monster when they destroy the house. Can you talk about how that was achieved?

Javier Verdugo: Well, each tale was distinctive. The first one looks more 2D, and the second one with the apothecary is more 3D but with stop motion. When it came to the house destruction tale, they wanted to keep some continuity between the live action monster and kid sequences. What we didn’t want is to have the kid look like a sticker. So that also was a big challenge because he has to live in a fantasy world, but we didn’t want him looking like a sticker or something too much like a fantasy watercolor environment.

We shared the monster asset with MPC. They gave us the asset, but we made it look a little bit different because we wanted the audience when they’re looking at this part of the tale to still be thinking that we’re inside of the tale – that we are walking in the world of the kid. So that’s why we made everything red, we made a different look.

There’s a significant amount of destruction in that tale for the house. How was that simulated?

Javier Verdugo: We were working with Houdini because, although at the beginning we were more 2D, by this point the director wanted it more realistic, more inside of the movie. A Houdini artist worked for almost two months preparing the house to break for the shot. We were destroying it shot by shot, taking a little bit of it off in one part, then another part, and another part, until the end.

In that sequence, you mentioned it had to not look too much like a fantasy sequence, but how did you find that balance because it is more pushed color-wise than just a normal scene?

Javier Verdugo: Everything that’s close to the kid is a little more realistic. But everything that’s far away like the sky, the trees, we tried to make it more like a painting. All the clouds are made from shooting inks that are expanding, so they feel like a cloud. We effectively made something like a 3D artistic environment, but when they are close to the kid we try to get more realistic. You feel that he’s inside of this environment.

Aside from Houdini, what other pieces of software were part of Glassworks’ toolset?

Javier Verdugo: Actually, something that people are surprised to learn about this project is that we used almost every 3D tool in the market right now. We used 3ds Max, Softimage, Cinema 4D, Modo, Maya, After Effects, Nuke, and Photoshop. We believe more in the people than in the package, so we didn’t care about how they did it, we cared about how they do it. If someone wanted to do their work in 3ds Max, we said do it in that. And then to do the frame-by-frame painting we used Photoshop and TVPaint.

The film has been out a while now in Spain, but what do you remember most about working on those tales?

It was an amazing project and right from the beginning we saw that it was going to be a special movie. I really want to thank Headless and J.A. [Bayona]. We knew from the beginning that to put these tales inside of a movie was going to be really hard. We worked really hard, and we were all really tight at the end, but now we see it was such a special project and we are really proud of everybody who worked on it.

Some additional breakdowns and final stills:

.png)